Вернуться на страницу ежегодника Следующая статья

I. Social-Political and Civilizational Aspects

The Age of the State and Sociopolitical Destabilization: Preliminary Results of the Quantitative Analysis* (Download pdf)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6354-2_02

Leonid E. Grinin, HSE University, Moscow, Russia; Institute of Oriental Studies, RAS, Moscow, Russia

Stanislav E. Bilyuga, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

Andrey V. Korotayev, HSE University, Moscow, Russia; Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia

Anton L. Grinin, Moscow State Lomonosov University, Moscow, Russia; HSE University, Moscow, Russia

Abstract

The article provides a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the correlation between the age of state and statehood as a whole and the risk of state destabilization. On the whole, an inversely proportional relationship has been revealed. All things equal, the longer a state exists, the lower the risk of its destabilization. A quantitative analysis of the correlation between the logarithm of the age of states and the integral CNTS index of sociopolitical destabilization is presented. In the paper the decile correlation analysis is used as the main method, as simple parametric linear regression in this case greatly underestimates the real strength of the relationship. In general, the decile analysis shows strong correlation between the logarithm of the age of statehood and the mean value of the aggregate index of sociopolitical destabilization (r = 0.81) and statistically significant (p = 0.004). Overall, the logarithm of the age of statehood explains about 66 % of the variance of the aggregate index of sociopolitical destabilization by deciles. An explanation for this correlation is presented. It is shown that a particularly high level of sociopolitical instability is characteristic of very young states under the age 9 years. But the transition to the next time period (9–25 years) results in a significant reduction in the average level of sociopolitical instability. An especially marked increase in the level of stability of states occurs during the transition to the time period of 25–35 years. Overall, the average level of sociopolitical instability for the oldest states (with an age of more than 200 years) appears to be more than 30 times lower than for the youngest states. The analysis shows the high potential of sociopolitical destabilization inherent in any kind of separatism/independence struggle. Even if the struggle for independence is conducted under absolutely just slogans, it is still associated with serious long-term risks of sociopolitical destabilization simply because the creation of any new state significantly increases the risks of sociopolitical destabilization in the respective territory for coming years.

Keywords: age of state, statehood, stateness, destabilization, young state, failed states, Africa, risks of sociopolitical destabilization.

Introduction

Although the relationship between the development of the state, its ability to withstand destabilizing influences, on the one hand, and the age of statehood, on the other hand, seems obvious, the analysis of this relationship has clearly not received enough attention in the literature, and in the works that address these issues, the analysis is not conducted in a systematic way. In fact, this is the case with the theory of nation-building; this theory is also linked to research based on social integration theory. This trend emerged in the 1950s and experienced a boom in the 1970s and the 1990s – the 2000s. Since nation-building could not ignore ethnic aspects, some researchers have noted that ‘there has been some ethnic basis for the construction of modern nations’ (Smith 1986: 147). Accordingly, it is easier for a more mature ethnic group to create a state.

Within that framework, the very concept of the nation state has been explored. It has been argued that nations are the product of industrialization and modernization and that the desire to have its own state appears together with the formation of a nation (see, e.g., Gellner 1983, 1991; Grinin 2008, 2010, 2011a, 2012a). Accordingly, the more experience nation-building has, the more successful the creation of one's own state will be. But these authors did not draw direct conclusions as to how the age of the state affects its stability.

Within the framework of the analysis of failed states and the successes and failures of the U.S. in nation-building, some researchers also indirectly linked the age of statehood and the success of such building. The book edited by F. Fukuyama Nation Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq (2006) can be mentioned here. Fukuyama writes that the U.S. had far more success in helping to rebuild war-torn societies, such as postwar Japan and Germany, than in building states fr om scratch. Of course, this is not coincidental. But it is due to the fact that states with a long existence of statehood are much more capable of successful reform and reconstruction than new states (Ibid.). In any case, nation-building takes a lot of time. Pointing this out in his review of the above-mentioned book edited by F. Fukuyama, G. J. Ikenberry (2006а) also established an important fact, both in itself and within the framework of our study, that successful cases of the US-sponsored nation-building

apparently, are associated with the American military presence in the respective countries. The efforts in Cuba lasted for a short time, less than a decade, and ultimately ended in failure. The democratic state building in the Philippines was successful, although it took 50 years for the United States to grant independence to the Philippines, and then almost another 50 years to finally withdraw its military forces fr om there (Ibid.: 153; Idem 2006b).

Thus, the adherents of this direction conclude that successful nation-building requires strict measures over a long period of time.

It is also worth mentioning Samuel Huntington's monograph Political Order in Changing Societies (Huntington 1968). Although he does not explicitly analyze the relationship between the age of statehood and stability, but he clearly implies this by starting his research with the following assertion,

The most important political distinction among countries concerns not their form of government but their degree of government. The differences between democracy and dictatorship are less than the differences between those countries whose politics embodies consensus, community, legitimacy, organization, effectiveness, stability, and those countries whose politics is deficient in these qualities. Communist totalitarian states and Western liberal states both belong generally in the category of effective rather than debile political systems… In all these characteristics the political systems of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union differ significantly fr om the governments which exist in many, if not most, of the modernizing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America... [where there is] a shortage of political community and of effective, authoritative, legitimate government (Huntington 1968: 1–2).

As an important factor contributing to the emergence of effective state power, Huntington (Ibid.: 21) identifies strong, adaptable and coherent social institutions, recognition by citizens of the legitimacy of authority and effective bureaucracies (as well as some other characteristics), which obviously requires the long existence of stateness and the perception by residents of the state as the only possible type of political organization in the relevant territory (see below), which can also be achieved only due to long history of statehood.

Nevertheless, despite such indirect conclusions about a direct positive relationship between the duration of the state and its strength (and an inverse negative relationship between the age of the state and the strength of the destabilization processes), there is little research in which this relationship is a central theme.

Although this issue remains insufficiently explored in the scientific literature, there are still works devoted to the study of the influence of the age of statehood on some factors related to its stability.

Special attention is given to the state experience. Thus, it is noted that younger states usually have less fiscal capacity than older ones (Tilly 1992; Collier 2009). At the same time, it has been pointed that with the increase in the age of the state, the amount of rent that the government office receives fr om the population may also increase which can lead to some economic stagnation (Olson 1982). In addition, according to some authors, despite an established bureaucratic infrastructure older states tend to be more autocratic in conditions of instability and excessive tax collection (Idem 1993).

While examining the relationship between the existence of the state and the income levels, S. P. Harish and Ch. Paik found an inverse U-shaped relationship between the mean duration of state rule and GDP per capita (Harish and Paik 2016). Against the background of the strong correlation between the level of GDP per capita and the intensity of coups (Belkin and Schofer 2003; Bouzid 2011; Korotayev, Vaskin et al. 2017, 2018; Korotayev, Grinin et al. 2017: 59–63) this would seem to suggest the possibility of an inverted U-shaped relationship between the duration of state rule and the intensity of coups and coup attempts[1].

On the other hand, Ch. Kenny used the age of the independent state existence as one of the independent regression variables to identify the factors influencing the level of per capita income for OECD countries. This variable turned out to be statistically significantly positive relation to per capita income (Kenny 1999), which in the light of the above considerations makes us to suggest that there is a statistically significantly negative correlation between the age of state existence and at least the intensity of coups.

As is easy to see, the research is insufficient and even contradictory which makes it worthwhile to conduct a special quantitative study of the general correlation between the age of the state and its characteristic level of socio-political instability.

Materials and Methods

For an empirical assessment of the degree of sociopolitical stabilizing influence of the age of statehood as an independent variable, we calculated the time indicator of the state existence.

The calculation was based on the date of independence for each state (see Appendix) taken from the historical dictionary A Dictionary of World History (Kerr and Wright 2015), published by Oxford University Press in 2015. The Soviet Historical Encyclopaedia in 16 volumes (Zhukov 1961–1976) and the reference books World Countries were also used to clarify the dates (see Goryachkina and Yarich 1986, 2005, 2017, etc.).

The integral socio-political destabilization index CNTS (Cross National Time Series database [Banks and Wilson 2017] was taken as a dependent variable, variable domestic9)[2].

We used decile correlation analysis as the main method, since a simple parametric linear regression in this case significantly underestimates the real strength of the relationship. The fact is that a simple parametric Linear Least Squares regression assumes the normal distribution of the dependent variable (see, e.g., Hilbe 2011). Meanwhile, the variables describing the intensity of sociopolitical destabilization are characterized by distribution that is different from normal with a disproportionately large number of zero values. Therefore, in this case, it makes sense to use for the analysis the aggregate values of the relevant indicator for the relevant years by deciles – the average value of the aggregate sociopolitical destabilization index CNTS for all decile country-years, which allows to normalize the distribution. We used the logarithm of the age of statehood to normalize the distribution by state age.

Test

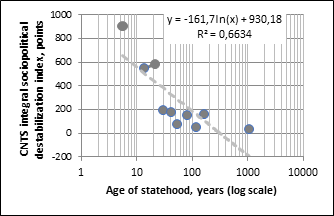

A decile correlation analysis of the relationship between the logarithm of the age of statehood and the CNTS integral sociopolitical destabilization index for the period of 1919–2015 gives the following results (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Correlation between the logarithm of the age of statehood and mean per decile values of the CNTS integral sociopolitical destabilization index normalized per million people for the corresponding year, 1919–2015 (scatter plot with fitted logarithmic regression line)[3]

Sources: Banks and Wilson 2017; Riches and Palmowski 2016.

Note: R2 = 0.66, r = 0.814, p = 0.004.

As we can see, the highest average value of the integral socio-political destabilization index CNTS (over 900) is typical for 10 % of the youngest states (i.e., the states of the first decile with the age of less than nine years). The average value of the destabilization index is on average less by one third for the states of the second and third deciles (with the age of 9–25 years). The average value of the socio-political destabilization index for the states of the fourth decile (25–35 years) is almost five times less than for the youngest states of the first decile. Particularly low values of the socio-political destabilization index are among the oldest states (with the age of more than 200 years) – the mean value of the instability index for them is more than 30 times less than for the youngest states!

On the whole, the correlation between the logarithm of the age of statehood and the average value of the aggregate sociopolitical destabilization index is strong (r = 0.81) and obviously statistically significant in a decile analysis (p = 0.004). The logarithm of the age of statehood explains about 66 % of the variance of the aggregate sociopolitical destabilization index by deciles.

Note that a pronounced deviation is the 9th decile of countries with an age of 140 to 205 years, among which we observe a significantly high average level of intensity of sociopolitical destabilization than would be expected based on the regression equation. In our opinion, it is explained by the fact that a very high proportion in this group of countries is Latin American states. As we know, stateness in these countries was formed facing a number of difficulties due to the lack of established nations and the common spread of the Spanish language, which made the borders between the countries rather conventional. It should be noted that during the Spanish colonial period, the borders between the future countries were not established as state borders. But after the War of Independence, as a result of continuous wars they changed frequently. In addition, statehood in these countries for a long time (up to the present) was formed with a disproportionately high role of the military strata, which led to constant military coups[4]. The development of stateness was also hindered by the weak integration of nations in the countries of this continent, taking into account the diverse racial and ethnic composition of the population and antagonism between the Creole upper strata and the majority of the Indian population. Another important feature was the permanent conflict between those who tried to establish a democratic system and the military, who constantly committed coups. Unlike European and Asian countries wh ere the statehood was based on the strong legitimacy of the monarchical system and the recognition of the ruling dynasties, in Latin America the legitimization of the state system was weak and led to widespread lawlessness, corruption and the break from tradition. Thus, despite a nominally long history of statehood in these countries statehood there in the modern sense of the word has developed quite recently.

Discussion

On the whole, obtained results correlate well with some of the results of our previous studies. In our works (see Grinin 2009, 2010, 2013a, 2013b, 2012b, 2013c, 2015a, 2015b, 2022b; Grinin and Korotayev 2016: Ch. 2, 3; 2024b) we have repeatedly mentioned the important fact that a long experience of statehood and nation-building is necessary for the creation of a more or less sustainable state.

Using various societies as examples, we have considered it from different aspects.

Firstly, we have investigated the typology of statehood and concluded that the most sustainable statehood is the so-called mature state corresponding to the period of industrialization and modernization (Grinin 2010). However, young states, especially those without a history of statehood and populated by immature ethnic formations (this correlates with what is called tribalism), cannot immediately establish such a type of statehood. In many respects, this statehood still resembles the most archaic type – the early state (Idem 2011b; Grinin 2008).

Accordingly, not all of these states have sovereignty. At the same time, there are a number of theories in which the ‘quality’ of sovereignty of countries of different levels and degrees of independence (e.g., so-called quasi-states [Jackson 1990], fragile states [Hagesteijn 2008], failed states [Rotberg 2004], ‘defective’, ‘incomplete’ states, etc.) differs. We have shown that failed states are either young states without traditions of statehood, or those in which statehood is sporadic or not well-established, forming a more or less fragile superstructure, and the bulk of the population is governed by other (non-state) forms (e.g., Afghanistan). One can agree with R. Hagesteijn's statement (2008) that it makes sense to make comparisons between fragile states and early state, which is usually only a superstructure over the society (for more details see Grinin 2003, 2011a, 2012a). The countries with stronger traditions of statehood have more chances to overcome a severe crisis (e.g., Ethiopia, Kampuchea and Laos). In addition, when analyzing particular societies' successfulness along with their neighbours' failures in terms of the strength and sustainability of the regime, it is often possible to find that this strength is not accidental, but related to more stable traditions of statehood than among neighbours. Let us take, for example, Morocco, which managed to get through the period of the Arab Spring period without upheavals mainly due to the regime of the constitutional monarchy, since according to the constitution (2011), in Morocco the king is the spiritual head of the Moroccan Muslims and a symbol of national unity which strengthens the legitimacy of his power in relation to Muslims. In addition, statehood in Morocco has deeper roots than, say, in Tunisia or Algeria, and in general, the traditions of statehood and monarchism in Morocco are stronger than in many other countries of the Middle East. Royalty is inherited in the direct male line in the Alaouite family (ruling since the 1730s), who are descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. All this serves as additional bonds keeping society from destabilization (Landa and Savateev 2015: 162).

The problems of young states are particularly characteristic of Africa. This is one of the main reasons why we forecast that Africa will become the most troubled continent of the World System in the future (see, e.g., Grinin 2022b; Grinin and Korotayev 2023a, 2023b, 2024a, 2024b; Korotayev, Shulgin et al. 2023; Medvedev et al. 2022; Ustyuzhanin and Korotayev 2022; Zinkina and Korotayev 2022a, 2022b). The process of rapid modernization in any state poses an increased risk of destabilization, and in the context of Africa, the risk is particularly increased (Grinin 2022a; Korotayev, Zinkina et al. 2011).

The young age of most states in Africa also gives us grounds to conclude that in the 21st century (possibly already in its first half) it is Africa that will be the continent wh ere the greatest number of revolutions, conflicts, and extremist explosions will occur, due to the fact that African countries are still in the process (often in the initial stages) of modernization, urbanization, formation of ethno-political nations, and the development of mature statehood.

The problems of young states are often associated with insufficient ‘cohesion’ between society and state. This is particularly characteristic of young, newly formed states in areas wh ere statehood has not been developed as a whole (e.g., in sub-Saharan Africa), wh ere the population realize themselves in a different social space (villages, tribes, small ethnic groups, etc.). We have concluded that the need for statehood (and in a certain form of a political regime) should become immanent in the public consciousness, become part of the mentality, culture and even the way of life of the population, which requires centuries of state traditions (by the way, in Latin America, a significant part of the population, especially the Indian, has not felt this need for a long time). According to Friedrich Ratzel, the boundaries should become the peripheral organs of the state, but not to remain an artificial border separating the territory inhabited by kindred tribes. Otherwise, instability, disintegration, permanent crisis are inevitable. In this regard, one should pay attention to the fact that most of the existing countries (and in Tropical Africa the absolute majority) have a very short (just a few decades) history of their national independence and, accordingly, sovereignty. The establishment of a sustainable stateness, as is well known, requires centuries, traditions and mentality of statehood.

It is not surprising that African countries consistently lead the list by Fragile States Index (Messner et al. 2015) (see Fig. 2). The conditions for a systemic crisis can arise when the level of engineering and technology (especially military) far exceeds the level of statehood. This is another reason for the formation of fragile or failed states.

Fig. 2. The map of failed states

Source: Messner et al. 2015.

Note: failed states are shaded with dark color

Secondly, we considered this issue in connection with certain types of crises in states (Grinin 2013a, 2013b, 2012b). In particular, we have found that crises in the state are associated with accelerated development in various spheres as a result of modernization (Grinin 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2022; Korotayev et al. 2018; Huntington 1968; etc.). A number of researchers highlighted the connection between revolution and modernization (see, e.g., Lipset 1959; Cutright 1963; Moore 1966; Dahl 1971; Brunk et al. 1987; Rueschemeyer et al. 1992; Burkhart and Lewis-Beck 1994; Londregan and Poole 1996; Epstein et al. 2006; Bois 2011; Huntington 1968; Hobsbaum 1999; Starodubrovskaya and Mau 2004; Goldstone 2015).

This aspect is important even because the need for economic reconstruction and development is formulated as recommendation for state-building (see, e.g., Dobbins et al. 2007). Otherwise the economy cannot be reconstructed and developed. In general, this is absolutely correct. It is impossible to create a modern state without a modern economy. However, one cannot ignore the fact that it is the rapidly developing societies that face the danger of falling into the trap of rapid transformation. One should remember that there are still a lot of states that are in the process of modernization or they are just at the beginning. Consequently, in the process of nation-building, special attention should be paid to preventing such imbalances in the socio-political system that can change it, which means that there is a need to find an internal consensus while preserving the development vector.

Thirdly, we have investigated the relationship between the absence or weakness of traditions of statehood and crises, in particular, in the Middle East (in Yemen, Libya, Syria [Grinin, Issaev, and Korotayev 2016; Grinin and Korotayev 2016, 2022; Grinin et al. 2019]), in some other countries (Grinin et al. 2015), as well as in Ukraine (Grinin 2014, 2015a, 2015b). As for Ukraine, it is obvious that the formation of statehood takes time; 30 years of independence are clearly not enough for this. The elite and the nation need experience, a clear understanding that one should live together, or the conviction that one should better separate. Our research has shown (Ibid.) that many seemingly strange, difficult to explain and frankly negative features of the foreign and domestic policy of modern independent Ukraine are largely due to the geopolitical and historical features of the state formation, mentality and established traditions of sociopolitical psychology (Barabash 2012). It is also obvious that many geopolitical and other factors of the past that negatively affect the stability of the state have not lost their significance today. Their modern influence is important for explaining and forecasting events in Ukraine.

At the same time, it should be noted that, on the one hand, the Ukrainian population, being under the rule of Russia (and Austria) for 250 years, acquired steady life skills within the framework of an organized state and developed a mentality of subordination to state discipline, as well as formed bureaucracy, i.e. numerous officials staff. This determines the fundamental differences between the Ukrainian nation and many young states (and some former territories of the USSR, such as Chechnya, as well as young African and some Middle Eastern states), whose population had neither experience of living in the mature state, nor a stable understanding of the conditions of this life. However, on the other hand, Ukraine did not have long experience of independent statehood, which seriously affects the behavior of the elite (which prefers to rely on foreign states rather than its own forces), especially in the absence of a clear domestic and external policy course.

Fourth, one cannot ignore the connection of the issue under consideration with the problems of instability of young democratic regimes (for the weaknesses of young democracies see Aron 1993; Grinin and Korotayev 2014; Grinin, Issaev, and Korotayev 2016; Korotayev, Slinko, and Bilyuga 2016; Korotayev et al. 2016, 2017, 2024; Kostin and Korotayev 2024; Slinko et al. 2017). The transition to democracy from monarchy, autocracy or other regime is always fraught with serious socio-political upheavals (see Aron 1993). However, if the transition to democracy occurs simultaneously with the creation of a new state (as it was in Ukraine and in many former colonies, and before that in Latin American countries), the risks of instability are doubled. Moreover, objectively speaking, the modern standard of the state regime (namely democratic with all the freedoms and universal suffrage) actually exceeds the achieved level of economic development of many modernizing countries. One should mention that Western democracy overcame a rather long path of limited democracy with rigid electoral qualifications, until it became (after the process of economic modernization and mainly after the completion of the demographic transition) the regime of full democracy. But even in this situation, many countries have not escaped revolutions.

Conclusion

Our quantitative analysis showed a strong and statistically significant correlation between the age of the state and the level of socio-political destabilization. A particularly high level of socio-political instability is characteristic of very young states under the age of nine years. The transition to the next time period (9–25 years) results in a significant reduction in the average level of sociopolitical instability. An especially marked increase in the level of stability of states occurs during the transition to the time period of 25–35 years. In general, the average level of sociopolitical instability for the oldest states (with an age of existence of more than 200 years) is more than 30 times lower than for the youngest states (under the age of nine years).

In conclusion, one should note that the age of the existence of the state is a very specific changing parameter. In fact, it cannot be quickly increased. The state needs more than 200 years in order to enter a relatively stable zone of ‘more than 200 years’. But it can be reduced very quickly, for this purpose it is enough to organize a successful separation of the territory from the old state and create a new state on it.

Thus, this analysis shows a powerful potential for sociopolitical destabilization inherent in any kind of separatism/struggle for independence. Even if the struggle for independence is conducted under perfectly just slogans, it is still associated with powerful long-term risks of sociopolitical destabilization, just because the creation of any new state significantly increases the risks of sociopolitical destabilization in the relevant territory for many years to come.

References

Aron R. 1993. Democracy and Totalitarianism. Moscow: Tekst. In Russian (Арон Р. Демократия и тоталитаризм. М.: Текст).

Banks A. S., and Wilson K. A. 2017. Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive. Databanks International. Jerusalem. URL: https://www.cntsdata.com.

Barabash B. 2012. Federalization of Ukraine: Panacea or a Dead End? (‘Zerkalo Nedeli’, Ukraine). InoSMI 27 November. URL: http://inosmi.ru/sngbaltia/20121127/202678003.html. In Russian (Барабаш Б. Федерализация Украины: панацея или тупик? («Зеркало Недели», Украина). ИноСМИ 27 ноября. URL: http://inosmi.ru/sngbaltia/20121127/202678003.html).

Belkin A., and Schofer E. 2003. Toward a Structural Understanding of Coup Risk. Journal of Conflict Resolution 47(5): 594–620.

Boix C. 2011. Democracy, Development, and the International System. American Political Science Review 105(04): 809–828.

Bouzid B. 2011. Using a Semi-Parametric Analysis to Understand the Occurrence of Coups d'état in Developing Countries. International Journal of Peace Studies: 53–79.

Brunk G. G., Caldeira G. A., and Lewis‐Beck M. S. 1987. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy: An Empirical Inquiry. European Journal of Political Research 15(4): 459–470.

Burkhart R. E., and Lewis-Beck M. S. 1994. Comparative Democracy: The Economic Development Thesis. American Political Science Review 88(04): 903–910.

Collier P. 2009. The Political Economy of State Failure. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25(2): 219–240.

Cutright P. 1963. National Political Development: Social and Economic Correlates. Politics and Social Life: An Introduction to Political Behavior / Ed. by N. W. Polsby, R. A. Dentler, and P. A. Smith, pp. 569–582. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Dahl R. A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dobbins J., Jones S. G., Crane K., and DeGrasse B. C. 2007. The Beginner's Guide to Nation-Building. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Epstein D. L., Bates R., Goldstone J., Kristensen I., and O'Halloran S. 2006. Democratic Transitions. American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 551–569.

Fukuyama F. (Ed.) 2006. Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gellner E. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gellner E. 1991. Nations and Nationalism. Moscow: Progress. In Russian (Геллнер Э. Нации и национализм. М.: Прогресс).

Goldstone J. 2015. Revolutions. A Very Brief Introduction. Moscow: Publishing House of the Gaidar Institute. In Russian (Голдстоун Дж. Революции. Очень краткое введение. М.: Изд-во Ин-та Гайдара).

Goryachkina T., and Yarich I. (Eds.) 2017. World Countries: A Modern Handbook. 2nd ed., revised and supplemented. Moscow: Slavyanskiy dom knigi. In Russian (Горячкина Т., Ярич И. (Ред.). Страны мира: современный справочник.2-е изд., перераб. и доп. М.: Славянский дом книги).

Grinin L. 2003. The Early State and Its Analogues. Social Evolution & History 1(1): 131–176.

Grinin L. 2008. Early State, Developed State, Mature State: The Statehood Evolutionary Sequence. Social Evolution & History 7(1): 67–81.

Grinin L. E. 2009. State and Historical Process. The Political Cut of Historical Process. 2nd ed. Мoscow: URSS. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и исторический процесс: Политический срез исторического процесса. М.: URSS).

Grinin L. E. 2010. State and Historical Process: The Evolution of Statehood: From the Early State to the Mature State. 2nd ed. Moscow: LIBROCOM. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и исторический процесс: Эволюция государственности: От раннего государства к зрелому. 2-е изд., испр. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ).

Grinin L. 2011a. The Evolution of Statehood. From Early State to Global Society. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Grinin L. E. 2011b. State and Historical Process. The Epoch of the State Formation: General Context of Social Evolution at the State Formation. 2nd ed. Moscow: LIBROCOM. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и исторический процесс. Эпоха формирования государства: Общий контекст социальной эволюции при образовании государства. 2-е изд. М.: ЛИБРОКОМ.)

Grinin L. 2012a. Macrohistory and Globalization. Volgograd: Uchitel.

Grinin L. 2012b. State and Socio-Political Crises in the Process of Modernization. Cliodynamics 3: 124–157.

Grinin L. E. 2013a. The State and Crises in the Process of Modernization. Filosofiya i obschestvo 3: 29–59. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и кризисы в процессе модернизации. Философия и общество 3: 29–59).

Grinin L. E. 2013b. The State and Its Crisis in the Past and Present. Vestnik Sibirskogo Instituta Biznesa i informatsionnykh tekhnologiy 3(7): 26–30. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Государство и его кризис в прошлом и настоящем. Вестник Сибирского института бизнеса и информационных технологий 3(7): 26–30).

Grinin L. 2013c. State and Socio-Political Crises in the Process of Modernization. Social Evolution & History 12(2): 35–76.

Grinin L. E. 2014. The Ukrainian State as an Incomplete Political Project: Fragmented Past, Crisis Present, Unclear Future. Istoricheskaya psikhologiya i sotsiologiya istorii 7(1): 5–37. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Украинское государство как незавершенный политический проект: фрагментарное прошлое, кризисное настоящее, неясное будущее. Историческая психология и социология истории 7(1): 5–37).

Grinin L. E. 2015a. Historical and Geopolitical Causes of the Socio-Political Crisis in Ukraine. Соцiальнi та полiтичнi конфiгурацii модерну: полiтична влада в Украiнi та свiтi: матерiали IV мiжнар. наук.-практ. конф. М. Киiв, 3–4 червня 2015 р. / Сост. Г. Дерлугьян, А. А. Мельниченко, П. В. Кутуев, А. О. Мiгалуш, pp. 34–35. Kiev: Talkom.

Grinin L. E. 2015b. The Ukrainian State as an Incomplete Political Project: Fragmented Past, Critical Present, Unclear Future. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks: The Ukrainian Rift / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, L. M. Issaev, and A. R. Shishkina, pp. 84–126. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е. Украинское государство как незавершенный политический проект: фрагментарное прошлое, кризисное настоящее, неясное будущее. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков: Украинский разлом / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, Л. М. Исаев, А. Р. Шишкина, c. 84–126. Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L. 2022a. Revolutions and Modernization Traps. Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 219–238. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_8.

Grinin L. 2022b. Revolutions of the 21st Century as a Factor of the World System Reconfiguration. Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 973–996. Cham: Springer Nature.

Grinin L. E., Issaev L. M., and Korotayev A. V. 2016. Revolutions and Instability in the Middle East. 2nd ed. revised, supplemented. Мoscow: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Исаев Л. М., Коротаев А. В. Революции и нестабильность на Ближнем Востоке. 2-е изд., испр. и доп. М.: Моск. ред. изд-ва «Учитель»).

Grinin L. E., and Korotayev A. V. 2014. Revolution vs Democracy (Revolution and Counterrevolution in Egypt). Polis 3: 139–158. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Kоротаев А. В. Революция vs демократия (революция и контрреволюция в Египте). Полис 3: 139–158).

Grinin L. E. and Korotayev A. V. 2016. The Middle East, India and China in Globalization Processes. Moscow: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Kоротаев А. В. Ближний Восток, Индия и Китай в глобализационных процессах. М.: Моск. ред. изд-ва «Учитель»).

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2022. The Arab Spring: Causes, Conditions, and Driving Forces. Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change / Ed. by J. A. Goldstone, L. Grinin, and A. Korotayev, pp. 595–624. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_23

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2023a. Africa – The Continent of the Future. Challenges and Opportunities. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 225–238. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_13

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2023b. The Future of Revolutions in the 21st Century and the World System Reconfiguration. World Futures 79(1): 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2022.2050342

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2024a. Africa – The Continent of the Future. Demographic and Economic Challenges and Opportunities. World Futures 80(1): 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2024.2315262

Grinin L., and Korotayev A. 2024b. Discussion among the Fifth-Generation Circle. A Rejoinder to Mark Beissinger, Daniel Ritter, Valentine Moghadam, Egor Fain, and Alisa Shishkina. Critical Sociology 50(6): 1109–1141. https://doi.org/10.1177/08969205241254125

Grinin L. E., Korotayev A. V., Issaev L. M., and Shishkina A. R. 2015. Introduction. Reconfiguration of the World-System and Increasing Risks of Political Instability. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks: The Ukrainian Rift / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, L. M. Issaev, and A. R. Shishkina, pp. 4–19. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Гринин Л. Е., Коротаев А. В., Исаев Л. М., Шишкина А. Р. Введение. Реконфигурация Мир-Системы и усиление рисков политической нестабильности. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков: Украинский разлом / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, Л. М. Исаев, А. Р. Шишкина, c. 4–19.Волгоград: Учитель).

Grinin L., Korotayev A., and Tausch A. 2019. Islamism, Arab Spring, and the Future of Democracy. World System and World Values Perspectives. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91077-2

Hagesteijn R. R. 2008. Early States and ‘Fragile States’: Opportunities for Conceptual Synergy. Social Evolution & History 7(1): 82–106.

Harish S. P., and Paik C. 2016. State and Development: A Historical Study of Europe from 0 AD to 2000 AD (No. 219). Households in Conflict Network.

Hilbe J. 2011. Negative Binomial Regression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hobsbawm E. 1999. The Age of Revolution. Europe 1778–1848. Rostov-on-Don: Feniks. In Russian (Хобсбаум Э. Век революции. Европа 1778–1848. Ростов н/Д.: Феникс).

Huntington S. P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ikenberry G. J. 2006a. Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq by Francis Fukuyama. Foreign Affairs 85(3): 152–153.

Ikenberry G. J. 2006b. Liberal Order and Imperial Ambition: Essays on American Power and International Order. Cambridge: Polity.

Jackson R. H. 1990. Quasi-States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kenny Ch. 1999. Why aren't Countries Rich? Weak States and Bad Neighbourhoods. The Journal of Development Studies 35(5): 26–47.

Kerr A., and Wright E. (Eds.) 2015. A Dictionary of World History. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. URL: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199685691.001.0001/acref-9780199685691.

Khokhlova A. A., Korotayev A. V., and Tsirel S. V. 2017. Unemployment and Social and Political Destabilization in Western and Eastern Europe: The Experience of a Quantitative Analysis. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks / Ed. by L. E. Grinin, A. V. Korotayev, L. M. Issaev, and K. V. Meshcherina, pp. 37–82. Volgograd: Uchitel. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Хохлова А. А., Цирель С. В. Безработица и социально-политическая дестабилизация в странах Западной и Восточной Европы: опыт количественного анализа. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков / Отв. ред. Л. Е. Гринин, А. В. Коротаев, Л. М. Исаев, К. В. Мещерина, c. 37–82. Волгоград: Учитель).

Korotayev A. V., Grinin L. E., Issaev L. M., Bilyuga S. E., Vas'kin I. A., Slinko E. V., Shishkina A. R., and Meshcherina K. V. 2017. Destabilization: Global, National, Natural Factors and Mechanisms. Moscow: Uchitel. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Гринин Л. Е., Исаев Л. М., Билюга С. Э., Васькин И. А., Слинько Е. В., Шишкина А. Р., Мещерина К. В. Дестабилизация: глобальные, национальные, природные факторы и механизмы. М.: Моск. ред. изд-ва «Учитель»).

Korotayev A., Shulgin S., Ustyuzhanin V., Zinkina J., and Grinin L. 2023. Modeling Social Self-Organization and Historical Dynamics. Africa's Futures. Reconsidering the Limits to Growth. A Report to the Russian Association of the Club of Rome / Ed. by V. Sadovnichy et al., pp. 461–490. Cham: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34999-7_20

Korotayev A. V., Slinko E. V., Shulgin S. G., and Bilyuga S. E. 2016. Intermediate Types of Socio-Political Regimes and Socio-Political Instability: The Experience of Quantitative Cross-National Analysis. Politia: Analiz. Khronika. Prognoz 3: 31–51. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Слинько Е. В., Шульгин С. Г., Билюга С. Э. Промежуточные типы социально-политических режимов и социально-политическая нестабильность: опыт количественного кросс-национального анализа. Полития: Анализ. Хроника. Прогноз 3: 31–51).

Korotayev A. V., Vaskin I. A., and Bilyuga S. E. 2017. Olson – Huntington Hypothesis on the Curvilinear Relationship between the Level of Economic Development and Socio-Political Destabilization: The Experience of Quantitative Analysis. Sotsiologicheskoye obozreniye 16(1): 9–49. In Russian (Коротаев А. В., Васькин И. А., Билюга С. Э. Гипотеза Олсона – Хантингтона о криволинейной зависимости между уровнем экономического развития и социально-политической дестабилизацией: опыт количественного анализа. Социологическое обозрение 16(1): 9–49).

Korotayev A., Vaskin I., Bilyuga S., and Ilyin I. 2018. Economic Development and Sociopolitical Destabilization: A Re-Analysis. Cliodynamics 9(1): 59–118. https://doi.org/10.21237/c7clio9137314

Korotayev A., Zhdanov A., Grinin L., and Ustyuzhanin V. 2024. Revolution and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century. Cross-Cultural Research: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971241245862

Korotayev A., Zinkina J., Kobzeva S., Bogevolnov J., Khaltourina D., Malkov A., and Malkov S. 2011. A Trap at the Escape from the Trap? Demographic-Structural Factors of Political Instability in Modern Africa and West Asia. Cliodynamics 2(2): 276–303. https://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio22217

Kostin M., and Korotayev A. 2024. USAID Democracy Promotion as a Possible Predictor of Revolutionary Destabilization. Comparative Sociology 23(2): 240–278. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-bja10102

Landa R. G., and Savateyev A. D. 2015. Political Islam in North Africa. Islamic Radical Movements on the Political Map of the Modern World. Vol. 1 / Ed. by A. D. Savateyev, and E. F. Kisriyev, pp. 126–180. Moscow: Lenand. In Russian (Ланда Р. Г., Саватеев А. Д. Политический ислам в странах Северной Африки. Исламские радикальные движения на политической карте современного мира. Т. 1 / Отв. ред. А. Д. Саватеев, Э. Ф. Кисриев, pp. 126–180. М.: Ленанд).

Lipset S. M. 1959. Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy. American Political Science Review 53(1): 69–105.

Londregan J. B., and Poole K. T. 1996. Does High Income Promote Democracy? World Politics 49: 1–30.

Medvedev I., Ustyuzhanin V., Zhdanov A., and Korotayev A. 2022. Application of Machine Learning Methods to Rank Factors and Predict Unarmed and Armed Revolutionary Destabilization in the Afrasian Macrozone of Instability. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks 13: 131–210. https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6184-5_06. In Russian (Медведев И. А., Устюжанин В. В., Жданов А. И., Коротаев А. В. Применение методов машинного обучения для ранжирования факторов и прогнозирования невооруженной и вооруженной революционной дестабилизации в афразийской макрозоне нестабильности. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков 13: 131–210).

Messner J. J., Nate H., Taft P., and Blyth H. (Eds.) 2015. Fragile States Index. The Fund for Peace. Report. URL: https://library.fundforpeace.org/library/fragilestatesindex-2015.pdf.

Moore B. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Olson M. 1982. The Rise and Decline of Nations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Riches Ch., and Palmowski J. (Eds.) 2016. A Dictionary of Contemporary World History. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. URL: http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191802997.001.0001/acref-9780191802997.

Romantsova S. (Ed.) 2005. Countries of the World: Travellers' and Erudites' Guide. Kharkov. In Russian (Романцова С. Страны мира: справочник для эрудитов и путешественников. Харьков).

Rotberg R. (Ed.) 2004. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Harvard, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rueschemeyer D., Stephens E. H., and Stephens J. D. 1992. Capitalist Development and Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Slinko E., Bilyuga S., Zinkina J., and Korotayev A. 2017. Regime Type and Political Destabilization in Cross-National Perspective: A Re-Analysis. Cross-Cultural Research 51(1): 26–50.

Smith A. D. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Blackwell.

Starodubrovskaya I., and Mau V. 2004. Great Revolutions. From Cromwell to Putin. Moscow: Vagrius. In Russian (Стародубровская И., Мау В. Великие революции. От Кромвеля до Путина. М.: Вагриус).

Tilly C. 1992. Coercion, Capital and European States: AD 990–1992. Wiley-Blackwell.

Ustyuzhanin V., and Korotayev A. 2022. Regression Modeling of Armed and Unarmed Revolutionary Destabilization in the Afrasian Macrozone of Instability. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks 13: 211–244. https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6184-5_07. In Russian (Устюжанин В. В., Коротаев А. В. Регрессионное моделирование вооруженной и невооруженной революционной дестабилизации в афразийской макрозоне нестабильности. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков 13: 211–244).

World Countries. 1986. A Reference Book. Moscow: Politizdat. In Russian (Страны мира: справочник. М.: Политиздат).

Zhukov E. M. (Ed.) 1961–1976. Soviet Historical Encyclopedia. Moscow: Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya. In Russian (Жуков Е. М. Советская историческая энциклопедия. М.: Сов. Энциклопедия).

Zinkina J. V., and Korotayev A. V. 2022a. Forecasting Some Demographic Structural Risks of Socio-Political Destabilization in the Countries of Eastern and Southern Africa. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks 13: 363–402. DOI: 10.30884/978-5-7057-6184-5_11. In Russian (Зинькина Ю. В., Коротаев А. В. К прогнозированию некоторых структурно-демографических рисков социально-политической дестабилизации в странах Восточной и Южной Африки. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков 13: 363–402).

Zinkina J. V., and Korotayev A. V. 2022b. Forecasting Some Demographic Structural Risks of Socio-Political Destabilization in the Countries of Northern and Western Africa. Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks 13: 322–362. DOI: 10.30884/978-5-7057-6184-5_10. In Russian (Зинькина Ю. В., Коротаев А. В. К прогнозированию некоторых структурно-демографических рисков социально-политической дестабилизации в странах Северной и Западной Африки. Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков 13: 322–362).

Appendix

Database on the Age of Statehood

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Afghanistan | 1919 | Independence from the UK | Afghanistan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Albania | 1913 | Independence from the Ottoman Empire | Albania. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Algeria | 1962 | Independence from France | Algeria. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Andorra | 803 | Independence from the Crown of Aragone | Andorra. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Angola | 1975 | Independence from Portugal | Angola. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Antigua and Barbuda | 1981 | Independence from the UK | Antigua and Barbuda. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Argentina | 1816 | Declared independence from Spain | Argentina. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Armenia | 1990 | Independence from the USSR | Armenia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Aruba | 1996 | Autonomy from the Netherlands | Aruba. A Dictionary… 2016 |

Australia | 1901 | Independence from the UK | Australia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Austria | 1918 | The First Republic | Austria. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Azerbaijan | 1991 | Independence from the USSR

| Azerbaijan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

The Bahamas | 1973 | Independence from the UK | Bahamas. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Bahrain | 1971 | Independence from the UK | Bahrain. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Bangladesh | 1971 | Independence from Pakistan | Bangladesh. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Barbados | 1966 | Independence from the UK | Barbados. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Belarus | 1991 | Independence from the USSR | Belarus. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Belgium | 1839 | Recognized independence from the Netherlands | Belgium. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Belize | 1981 | Independence from the UK | Belize. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Benin | 1960 | Independence from France | Benin. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Bhutan | 1907 | Monarchy under the Wangchuck dynasty | Bhutan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1992 | Independence from Yugoslavia | Bosnia and Herzegovina. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Botswana | 1966 | Independence from the UK | Botswana. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Brazil | 1822 | Recognized independence from Portugal | Brazil. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Brunei Darussalam | 1984 | Independence from the UK | Brunei Darussalam. |

Bulgaria | 1908 | Independence from the Ottoman Empire | Bulgaria. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Burkina Faso | 1960 | Independence from France | Burkina Faso. A Dictio-nary... 2015 |

Burundi | 1962 | Independence from Belgium | Burundi. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Cambodia | 1953 | Independence from France | Cambodia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Cameroon | 1960 | Independence from France | Cameroon. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Central African Republic | 1960 | Independence from France | Central African Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Chad | 1960 | Independence from France | Chad. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Chile | 1810 | Recognized independence from Spain | Chile. A Dictionary... 2015 |

China | 2070 | First Pre-imperial Dynasty | China. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Ciskei | 1981 | Nominal national state | Ciskei. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Costa Rica | 1838 | Recognized independence from Spain | Costa Rica. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Cote d'Ivoire | 1960 | Independence from France | Cote d'Ivoire. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Croatia | 1992 | Independence from Yugoslavia | Croatia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Czechoslovakia | 1918 | Independence | Czechoslovakia. A Dictio- |

Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1960 | Independence from Belgium | Congo, the Democratic Republic ... A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 1948 | Creation of the State | Korea, Democratic People's Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Denmark | 1320 | Unification | Denmark. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Djibouti | 1977 | Independence from France | Djibouti. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Dominica | 1978 | Independence from the UK | Dominica. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Dominican Republic | 1924 | Independence from the United States | Dominican Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

East Timor | 2002 | Restoration of independence | Timor-Leste. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Ecuador | 1822 | Recognized independence from Spain | Ecuador. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Egypt | 1922 | Independence from the UK | Egypt. A Dictionary... 2015 |

El Salvador | 1903 | The independent State | El Salvador. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Equatorial Guinea | 1968 | Independence from Spain | Equatorial Guinea. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Eritrea | 1993 | The legal status of the State | Eritrea. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Estonia | 1918 | Recognized independence | Estonia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Ethiopia | 1941 | Creation of the State | Ethiopia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Fiji | 1970 | Independence from the UK | Fiji. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Finland | 1919 | Recognized independence from the Russian Empire | Finland. A Dictionary... 2015 |

France | 1066 | Unification of France | France. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Gabon | 1960 | Independence from France | Gabon. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Gambia | 1965 | Independence from the UK | Gambia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Ghana | 1957 | Declared Independence from the UK | Ghana. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Georgia | 1991 | Recognized Independence from the USSR | Georgia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Germany | 1867 | German unification | Germany. A Dictionary... 2015 |

German Democratic Republic | 1949 | Division of Germany | German Democratic |

Greece | 1833 | Recognized Independence from the Ottoman Empire | Greece. A Dictionary... |

Grenada | 1974 | Independence from the UK | Grenada. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Guatemala | 1821 | Declared independence from Spain | Guatemala. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Guinea | 1958 | Independence from France | Guinea. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Guinea Bissau | 1974 | Recognized independence from Portugal | Guinea-Bissau. |

Houthi in North Yemen | 2015 | Assumption of power by the Houthis in the North of Yemen | Yemen North. A Dictio-nary... 2015 |

Iceland | 1944 | Withdrawal from the Danish Monarchy | Iceland. A Dictionary... 2015 |

India | 1947 | Independence from the UK | India. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Indonesia | 1945 | Declared independence from the Netherlands | Indonesia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Iran | 550 | Achaemenid Empire | Iran, Islamic Republic of. |

Iraq | 1932 | Independence from the UK | Iraq. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Ireland | 1921 | Independence from the UK | Ireland. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Israel | 1948 | Recognized independence | Israel. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Italy | 1861 | Unification of Italy | Italy. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Jamaica | 1962 | Independence from the UK | Jamaica. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Japan | 660 | Creation of the State | Japan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Jordan | 1946 | Mandate territory | Jordan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Kazakhstan | 1991 | Recognized Independence from the USSR | Kazakhstan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Kenya | 1963 | Independence from the UK | Kenya. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Kiribati | 1979 | Independence from the UK | Kiribati. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Korea, Republic | 1948 | Independence from Japan | Korea, Republic of. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Kosovo | 2008 | Declaration of Independence | Kosovo. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Kuwait | 1961 | Independence from the UK | Kuwait. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Kyrgyzstan | 1991 | Recognised Independence from the USSR | Kyrgyzstan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Qatar | 1971 | Independence from the UK | Qatar. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Lao People's Democratic Republic | 1953 | Independence from France | Lao People's Democratic Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Latvia | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Latvia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Lebanon | 1945 | Independence from France | Lebanon. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Lesotho | 1966 | Independence from the UK | Lesotho. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Liberia | 1847 | Recognized independence | Liberia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Libya | 1951 | Liberation from Britain and France | Libya. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Liechtenstein | 1866 | Liberation from Germany | Liechtenstein. A Dictio-nary... 2015 |

Lithuania | 1918 | Declaration of independence from Germany | Lithuania. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Luxembourg | 1815 | Independence from the Netherlands | Luxembourg. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Madagascar | 1960 | Independence from France | Madagascar. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Macedonia | 1993 | Recognized independence from Yugoslavia | Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia |

Malawi | 1964 | Independence from the UK | Malawi. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Malaysia | 1963 | Independence of the State | Malaysia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Maldives | 1965 | Independence from the UK | Maldives. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Mali | 1960 | Independence from France | Mali. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Malta | 1964 | Independence from the UK | Malta. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Mauritania | 1960 | Independence from France | Mauritania. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Mauritius | 1968 | Independence from the UK | Mauritius. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Morocco | 1956 | Independence of the State | Morocco. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Marshall Islands | 1991 | Independence of the State | Marshall Islands. A Dictio- |

Mexico | 1836 | Recognized independence from Spain | Mexico. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Micronesia | 1986 | Creation of the State | Micronesia, Federated States of. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Moldova | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Moldova, Republic of. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Monaco | 1861 | Creation of the State | Monaco. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Mongolia | 1911 | Independence from the Qing Empire | Mongolia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Montenegro | 2006 | Restoration of independence from Yugoslavia | Montenegro. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Mozambique | 1975 | Independence from Portugal | Mozambique. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Myanmar | 1948 | Independence from the UK | Myanmar. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Namibia | 1990 | Independence from South Africa | Namibia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Nauru | 1968 | Independence from the UK | Nauru. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Nepal | 1769 | Creation of the State | Nepal. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Netherlands Antilles | 1954 | Creation of the State | Netherlands Antilles. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Netherlands | 1648 | Creation of the State | Netherlands. A Dictionary... 2015 |

New Zealand | 1907 | Great Britain dominion | New Zealand. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Nicaragua | 1838 | Recognized independence from Spain | Nicaragua. |

Niger | 1960 | Independence from France | Niger. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Nigeria | 1960 | Recognized independence from the UK | Nigeria. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Norway | 1807 | Creation of the State | Norway. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Oman | 130 | Creation of the State | Oman. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Pakistan | 1947 | Great Britain dominion | Pakistan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Palau | 1994 | Compact of Free Association with the USA | Palau. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Palestine, state | 1988 | Declaration of independence | Palestine, State. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Panama | 1903 | Independence from Colombia | Panama. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Papua – New Guinea | 1975 | Recognized independence from Australia | Papua New Guinea. |

Paraguay | 1811 | Recognized independence from Spain | Paraguay. A Dictionary... 2015 |

The People's Democratic Republic of Yemen | 1967 | Creation of the independent state | Yemen People's Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Peru | 1821 | Recognized independence from Spain | Peru. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Philippines | 1946 | Independence from the USA | Philippines. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Poland | 1987 | Creation of the State | Poland. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Portugal | 1179 | Recognition of the State | Portugal. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Romania | 1878 | Independence from the Ottoman Empire | Romania. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Russian Federation | 1991 | Creation of the State | Russian Federation. |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Rwanda | 1962 | Independence from Belgium | Rwanda. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1983 | Independence from the UK | Saint Kitts and Nevis. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Saint Lucia | 1979 | Independence from the UK | Saint Lucia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Samoa | 1962 | Independence from New Zealand | Samoa. A Dictionary... 2015 |

San Marino | 1291 | Independence from the Roman Empire | San Marino. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Sao Tome and Principe | 1975 | Independence from Portugal | Sao Tome and Principe. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Saudi Arabia | 1932 | Creation of the State | Saudi Arabia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Senegal | 1960 | Independence from France | Senegal. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Serbia | 1878 | Creation of the Principality of Serbia | Serbia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Seychelles | 1976 | Independence from the UK | Seychelles. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Sierra Leone | 1961 | Independence from the UK | Sierra Leone. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Singapore | 1965 | Independence from the UK | Singapore. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Slovakia | 1993 | Independence from Czechoslovakia | Slovakia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Slovenia | 1991 | Independence from Czechoslovakia | Slovenia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Solomon Islands | 1978 | Independence from the UK | Solomon Islands. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Somalia | 1960 | Independence | Somalia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

The Soviet Union | 1922 | Treaty on the creation of the USSR | Soviet Union. A Dictionary... 2015 |

South Africa | 1961 | Independence from the UK | South Africa. A Dictionary... 2015 |

South Sudan | 2011 | Independence from Sudan | South Sudan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Sri Lanka | 1948 | Dominion of Great Britain | Sri Lanka. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

St.Vincent and the Grenadines | 1979 | Independence from the UK | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Sudan | 1956 | Independence from the UK | Sudan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Suriname | 1975 | Independence from the Netherlands | Suriname. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Swaziland | 1968 | Independence from the UK | Swaziland. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Sweden | 1523 | Creation of the State | Sweden. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Switzerland | 1848 | Unification of the State | Switzerland. |

Syrian Arab Republic | 1941 | Independence from France | Syrian Arab Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Taiwan | 1949 | Unrecognized independence from the PRC | Taiwan, Province of China. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Tajikistan | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Tajikistan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Tanzania | 1967 | Independence from the UK | Tanzania, United Republic. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Thailand | 1238 | Creation of the State | Thailand. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Togo | 1960 | Independence from France | Togo. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Tonga | 1970 | Independence from the UK | Tonga. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Transkei | 1976 | Creation of the State | Transkei. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Trinidad and Tobago | 1962 | Independence from the UK | Trinidad and Tobago. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Tunisia | 1955 | Independence from France | Tunisia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Turkey | 1923 | The legacy of the Ottoman Empire | Turkey. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Turkmenistan | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Turkmenistan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Tuvalu | 1978 | Independence from the UK | Tuvalu. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Uganda | 1962 | Independence from the UK | Uganda. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Continuation of Table

Country | Year of Independence | Status of the Country | Source |

Ukraine | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Ukraine. A Dictionary... 2015 |

The United Arab Emirates | 1971 | Independence from the UK | United Arab Emirates. A Dictionary... 2015 |

The United States of America | 1783 | Completion of the separation of the United States from Great Britain | United States. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Uruguay | 1828 | Independence from Brazil | Uruguay. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Yugoslavia | 1929 | Creation of the State | Yugoslavia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Uzbekistan | 1991 | Recognized independence from the USSR | Uzbekistan. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Zambia | 1964 | Recognized Independence from the UK | Zambia. A Dictionary... 2015 |

Zimbabwe | 1980 | Recognized Independence from the UK | Zimbabwe. A Dictionary... 2015 |

* This research has been supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project № 24-18-00650).

[1] It should be noted that our researches did not confirm this hypothesis.

[2] On the description and methodology of the Cross National Time Series (CNT) see Korotayev, Khokhlova, and Tsirel 2017: 37–82.

[3] Deciles by age of the statehood include the following values: the 1st decile – up to 9 years; the 2nd decile – from 9 to 17 years; the 3rd decile – from 17 to 25 years; the 4th decile – from 25 to 35 years; the 5th decile – from 35 to 47 years; the 6th decile – from 47 to 64; the 7th decile – from 64 to 99 years; the 8 decile – from 99 to 140 years; the 9th decile – from 140 to 205; the 10th decile – over 205 years.

[4] Thus, in the two decades after World War II, successful coups d'etats occurred in 17 of 20 Latin American countries (only Mexico, Chile and Uruguay maintaining constitutional processes) (Huntington 1968).