Вернуться на страницу ежегодника Следующая статья

The Extent of Military Involvement in Nonviolent Civilian Revolts and Their Aftermath (Download pdf)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/978-5-7057-6354-2_05

Karen Rasler, Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana, USA

William R. Thompson, Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Hicham Bou Nassif, Claremont McKenna College California, USA

Abstract

The paper deals with the analysis of the role of military's position in the outcomes of civilian uprisings and revolutions. Civilian protest campaigns (or revolutions) that appear to drive autocrats fr om office are dramatic affairs. However, in most cases it is not civilian protestors alone who can be credited for the regime change outcome. The military serve as significant veto players. They can work to keep the autocrats in office, they can support the civilian uprisings, or they can participate in some negotiated compromise that may be worked out. Whatever the case, the authors contend that the more significant and overt the military role in these affairs, the less likely it is that the post-revolutionary outcome is democratic in nature. How and to what extent they play a role is assessed through an investigation of 36 nonviolent, civilian revolts that brought about successful regime change since 1945. In each case, we measure, albeit crudely, the breadth of civilian participation and the nature of the military involvement. These indicators are then compared with democratization levels five and ten years after the nonviolent civilian revolt. The authors find that protest campaigns can certainly bring down regimes, but in most cases, only if the military permits it. When the military is least involved in toppling the regime, the new subsequent regime is likely to be more democratic. When the military is highly involved, the nature of the new regime is predictably less de-mocratic.

Keywords: military involvement, civilian revolts, revolutions, protests.

1. Military Involvement

As part of what has come to be known as the Arab Spring, three Middle Eastern autocrats lost their long-held political positions in Tunisia (Ben Ali), Egypt (Mubarak), and Yemen (al Saleh) as a result of nonviolent popular revolts.[1] Fr om 2010–2012, in fact, a quarter of all autocrats who left office did so in the context of a mass revolt (Kendall-Taylor and Franz 2014). More recent cases involve Omar Hassan al-Bashir (Sudan) and Abdelaziz Bouteflika (Algeria) in 2019.[2] Not only did these leadership changes occur, but a rewriting of the institutional rules of the political systems occurred as well. Like other cases of successful nonviolent civilian revolts[3], do they matter in the long run? Do they lead to less autocracy and more civilian rule? Or, do they eventually lead to disappointing outcomes associated with greater autocracy? The empirical record suggests that there is a great deal of variation in the possible outcomes of these campaigns. Recent empirical research that relies on cross-national data has demonstrated that nonviolent mass revolts have been associated with a greater rate of success in achieving democratic outcomes than violent campaigns (such as mass insurgencies). We argue, however, that the long-term outcomes of these nonviolent protest campaigns are complicated and yield more mixed results.[4] One reason for this is that behind the scenes of most nonviolent protest campaigns lurks the question of what the military will do. For instance, the name for the Georgian Rose Revolution is attributed to a last-minute decision to have civilian protesters carry long stem roses to show the military units defending the legislative building that the civilians were unarmed (on the Georgian Revolution see Khodunov 2022). Flowers in gun barrels often demonstrate some implicit military acceptance of civilian dissent, even if only at the lower ranks. But the problem remains that considerable uncertainty often characterizes civil-military relations as protest campaigns turn into explicit threats to the survival of an autocratic incumbent regime.

Not surprisingly, autocrats attempt to prolong their rule by using police and security forces to repress popular protests. Sometimes, they also call out the military to defend their threatened regimes. Sometimes, the military obliges and sometimes it does not. Armed forces can choose to remain neutral bystanders.[5] Or, they can intervene at the end of an intensifying protest campaign, remove the targeted ruler, and retain control of the state. Occasionally, the military will fragment into opposing factions. Regardless of what it actually decides to do, the military always has the potential to intervene on behalf of, or against, the political status quo, and for that reason it has the capacity to be a significant veto player in nonviolent civilian revolts.

We contend that the more significant and overt the military role in internal revolts, regardless of who their action is intended to benefit and including nonviolent civilian resistance campaigns, the less likely post-revolutionary politics will be as democratic as they might have been otherwise. Military interventions do not always lead to autocratic outcomes, but they are more likely to do so because the military usually prefers corporate interests, political order and stability over wide participation in politics.[6] If the military has been a major player in the political system, it will act to preserve its corporate and political interests regardless of who takes power.[7] To the extent that it is heavily involved in the political transition, its preferences are more likely to be translated into the structure of the ensuing political system.

Besides the military, we also acknowledge that other factors play an important role, such as the scale and scope of protest campaigns. Some research shows that broad-based campaigns (large numbers of protesters across political, economic and social sectors) are not only more likely to be successful in bringing down regimes but also associated with more democratic outcomes in their aftermath (Ackerman and Karatnycky 2005; Chenoweth and Stephan 2011: 61). We believe that such an outcome is certainly not guaranteed, because there is always the potential that a small and narrow group will emerge to dominate the revolutionary process either during or after the ousting of an incumbent group. Nonetheless, we maintain that for the most part, post-revolutionary regimes tend to resemble the organization of the group(s) responsible for overthrowing the old regime. This is especially true if a revolutionary party, religious group, or military leadership is at the head of the revolution.

This paper addresses how these two conflicting principles – nonviolent civilian protest and military involvement – have worked out in the past and how they might play out in the future. Nonviolent civilian revolts usually encompass a mix of both – civilian protests of varying size and scope and military involvement of various kinds. They are not normally complementary, but one or the other plays an important role in determining whether political systems transition to more democratic or autocratic outcomes. How and to what extent they play a role is determined through an investigation of 36 nonviolent civilian revolts that brought about successful regime change since 1945. In each case, we measure, albeit crudely, the breadth of civilian participation and the nature of the military involvement. These indicators are then compared with democratization levels five and ten years after the nonviolent civilian revolt. We hypothesize that higher levels of military involvement during these revolts will lead to less democracy, while nonviolent revolts that involve broad-based coalitions of civilian protesters with lesser military involvement will lead to more democracy.

2.

Theoretical and Empirical Research

on the Outcomes of Nonviolent Protest Campaigns

Most of the research that shows there is a positive association between successful protest campaigns and long-term democratization comes fr om cross-national quantitative studies that compare nonviolent and violent civilian campaigns. Unlike nonviolent campaigns, violent insurgencies reflect a state of rebellion where dissidents are committed to changing the status quo through tactics of armed force in the context of civil wars and secessionist movements. The evidence that nonviolent protest campaigns are associated with long-term democratization relative to violent campaigns is quite robust across different measures of democracy, control variables, cases and methodologies. For instance, after examining every regime transition fr om 1972 to 2005, Ackerman and Karatnycky (2005) find that those transitions that involved mainly nonviolent mass actions experienced higher levels of freedom (derived fr om Freedom House measures) in the long run than those actions that involved violent oppositions. Meanwhile, Johnstad (2010) follows up this study with statistical tests that relied not only on Freedom House measures but also data fr om Polity IV and The Economist Intelligence Unit's index of democracy. While controlling for economic growth, he shows that Freedom House, Polity IV and the Economist data all agree that transitions associated with major violence fr om opposition groups were less likely to result in long-term high quality democracy than transitions associated with nonviolent mass actions.

Stradiotto and Guo (2010) tackle this same question fr om a different theoretical and statistical angle. Using regression and hazard rate models, they ask whether a certain type of democratic transition mode will result in higher levels of democracy and endure the longest over ten years. Theoretically, they identify four types of transitions: conversion (elite led democratic reforms); cooperative (democratic reforms-based pacts between government and opposition groups); collapse (violent revolution-led reforms) and foreign intervention (externally imposed democratic reforms).

Of these four types, ‘cooperative transitions’ are mostly closely associated with nonviolent protest campaigns as the political process is marked by cycles of protests (strikes, demonstrations) and repression that lead to political compromise and reforms. Cooperative transitions are ‘opposition-led transitions’ where political outsiders successfully mobilize mass support to dislodge incumbent elites fr om their political positions. Cooperative transitions are usually associated with opposition groups and incumbents that are relatively equal in power, which contributes to bargaining and negotiation since neither side can be assured of victory through the use of violence. Consequently, these transitions are likely to lead to greater democratization through agreements about electoral rules, civilian-military relations, and the participation of new political actors.

Utilizing the Political Regime Dataset originally created by Gasiorowski (1996), Stradiotto and Guo identify regime changes in 57 countries fr om 1973 to 1995 as well as measure country-year democracy (Polity IV) scores for each. They control for region, type of institutional arrangement, prior regime type and democratic history, and finally income level. Their dependent variable of post-transition democratic levels is measured at three time intervals: as an average of three, six and ten years. Their regression results show that, as hypothesized, ‘cooperative’ transitions are strongly associated with higher democratic quality scores across all three time periods, while the remaining transition modes failed to have any significant effect across the same intervals. To examine the longevity of democracy, Stradiotto and Guo estimate hazard rate models which get at the question of democratic survival rates; their results show that cooperative transitions were associated with a statistically significant 96 % lower risk of democratic death than other transition modes.

Next, Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) produced a new dataset, NAVCO (Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes), documenting 323 violent and nonviolent resistance campaigns (102 of which were nonviolent) fr om 1900–2006. Controlling for the duration of these conflicts as well as the level of democracy at the end of these conflicts, they demonstrate that nonviolent campaigns were more likely to have a higher level of post-conflict democracy (as determined by various Polity IV measures) than violent ones, measured five years after the conflict ended.

Utilizing Chenoweth and Stephan's (2011) NAVCO dataset, Celestino and Gleditsch (2013) conduct a more sophisticated country-year analysis that included all nonviolent and violent cases with Polity IV measures of transitions from autocratic regimes to democracy, as well as transitions from one autocratic regime or coalition to another autocratic regime, from 1900–2004. They hypothesized that nonviolent campaigns are more likely to be associated with transitions from autocratic regimes to democracy, while violent campaigns would be associated with a transition from autocracy to another autocracy. They control for national income level, regime age, and the proportion of neighboring states were democratic. The last variable is based on prior research that shows transitions to democracy are more likely when autocracies have a high share of democratic neighbors (Gleditsch and Ward 2006).

Equally important, Celestino and Gleditsch (2013) lay out several causal mechanisms that account for why nonviolent campaigns will be associated with transitions to democracy, which have direct relevance for our study below. Nonviolent campaigns that bring together large numbers of participants across economic, political and social segments of society can bring down regimes by encouraging elite defections, forcing major governmental reforms, and escalating the scale and scope of the protests that result from backfire effects of state repression. In the aftermath of leadership changes, nonviolent campaigns are likely to produce greater democratization because the distribution of power is dispersed among many actors inside and outside of the government. Since there are many centers of political power among diverse actors engaged in the protests, political groups are likely to support power sharing arrangements that both reduce autocratic tendencies and support democratic practices. In short, nonviolent campaigns in comparison to violent ones are more likely to bring down regimes as well as foster democracy in the long run.

As for violent campaigns, Celestino and Gleditsch (2013) argue that they are both more likely to fail in bringing down regimes and more likely to increase autocratization in the long run. Since violent campaigns tend to occur in the periphery and involve smaller numbers of dissidents, states are more successful in defeating them through repression and military resources. Moreover, states that repress violent campaigns are likely to become more autocratic over time as those states centralize their authority through their defeat of armed opposition groups and the repression and/or marginalization of peaceful dissidents.

In a nutshell, Celestino and Gleditsch's empirical analyses (2013) show that nonviolent campaigns do indeed have a strong statistical impact, making transitions to democracy more likely, while violent campaigns have less association with long-term democracy but a significant long-term impact by raising the likelihood of later autocracy. An additional key finding is that nonviolent campaigns increase the probability of a democratic transition even more when there is a heavy presence of neighboring democratic states.

Additional research by Bayer et al. (2016) argues that democratic regimes that come into being as a result of a nonviolent resistance campaign are less prone to democratic breakdown when compared with democracies that were the result of violent resistance or those which were installed without any kind of resistance movement. They maintain that nonviolent protest campaigns produce a civic political culture that has stabilizing effects on the subsequent democratic regime. This civic culture creates constraints and incentives that encourage compromise and cooperation among various constituent interests, which insures democratic longevity in the post-transition period. Nonviolent protest campaigns thereby reduce political polarization and power struggles among political actors. Finally, nonviolent protest campaigns avoid the problems associated with the demobilization of armed groups and prior human rights violations that often complicate the transition process associated with violent campaigns. Bayer et al. (2016) therefore test the hypothesis that democratic regimes that have experienced nonviolent protest campaigns during their transition phases will survive longer than democratic regimes that have not experienced such campaigns.

Relying on two cross-national datasets, the NAVCO (2.0) version and Ulfelder's (2010) political regimes data, Bayer et al. (2016) combined information on the duration of democratic regimes with information on the presence of nonviolent protest campaigns during these transitions from 1955 to 2010 time period. They conducted hazard rate models for 112 democratic regimes, out of which 69 experienced a democratic breakdown, with the remaining 43 regimes being without a breakdown by the end of the time period. They controlled for GDP levels, military legacies, previous instability, population size, urbanization and the presence of neighboring democracies. Their hazard rate models demonstrate that nonviolent campaigns were associated with a statistically significant positive effect on the duration of democratic regimes. Bayer et al. (2016) concluded that there is a ‘democratic dividend of nonviolent resistance’ that increases the success rates for both transitions to democracy and their longevity.[8]

Recently, Kim and Kroeger (2019) examined the relationship between anti-regime protests (both violent and nonviolent) and democratic transitions in all authoritarian regimes from 1950 to 2007. They argue that there are four pathways to these outcomes as a result of mass revolts. One way is through the direct overthrow of an autocracy with the subsequent installation of a democratic regime. A second causal pathway is that mass revolts coerce incumbents into democratic reforms by threatening their survival. A third avenue is that mass revolts bring about elite splits which promote negotiated democratic reforms. Finally, such revolts encourage leadership change within the existing autocratic regime. Collecting a sample of 3,200 observations for 233 authoritarian governments, Kim and Kroger estimate a CRE (correlated random effects) probit model on democratic transitions and anti-regime protests.[9] They control for the effects of civil society strength, the history of recent national multiparty elections, the size of the military, GDP per capita, and the regional presence of other democracies. Their empirical evidence shows that anti-regime protests overall increase the probability of autocratic regime breakdowns. Moreover, nonviolent protests are associated with democratic transitions while violent protests are more likely to lead to autocratic transitions. While their empirical results corroborate Celestino and Gleditsch's (2013) earlier findings, Kim and Kroeger also find evidence for Celestino and Gleditsch's four causal mechanisms that link nonviolent protests and increased democratization.

3.

The Problem of Comparing Nonviolent

and Violent Campaigns

This body of empirical quantitative research is impressive, but we believe that comparing nonviolent protest campaigns with violent ones in determining the probability of long-term democratization is misleading. We suggest that there are significant conceptual differences between violent and nonviolent campaigns and any comparisons between the two will in all likelihood increase the probability of finding empirical results that associate nonviolent protest campaigns with long-term democratization trends, while violent ones will not have them.

In fact, Celestino and Gleditsch (2013: 390) make the case for us. They show that nonviolent and violent campaigns have significant differences in that violent campaigns (civil wars, insurgencies, revolutions) tend to be fought in the periphery and often involve groups that are ethnically distinct from the groups that dominate the political system. However, nonviolent campaigns are frequently urban phenomena which are typically broad-based across economic, political and social sectors. In addition, violent campaigns are frequently small guerrilla-type affairs and rest on a small recruitment base. In contrast, successful nonviolent campaigns are highly dependent on a large number of participants who create a bandwagon effect over time. Regimes are less likely to repress large-scale nonviolent actions given their concerns about generating backfire effects and increasing the probability of police/security/military defections or fragmentation.

Still, states are very likely to repress and justify the use of repression when they are faced with violent campaigns. Hence, a key intervening influence here is state repression which is likely to influence the long-term trajectories of both democratization and autocracy levels. States' reluctance to use repression increases the probability that nonviolent protest campaigns are likely to be successful in comparison to violent campaigns. And, greater willingness of the states to employ repression against armed insurgents is likely to generate spillover effects associated with greater state centralization and the political marginalization of opposition groups. Moreover, states' military advantages over violent insurgents are likely to produce campaign failures. Therefore, instead of comparing nonviolent and violent campaigns, we recommend that successful nonviolent protest campaigns should be compared by themselves.

In their path-breaking book, The Arab Spring: Pathways of Repression and Reform, Brownlee, Masoud, and Reynolds (2015) do exactly that. They compare three states whose leaders were brought down as a result of nonviolent protest campaigns in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen during 2011.[10] Although they explain what brought about mass protests and leadership changes in these cases, their later chapters are especially pertinent because the authors trace the reasons for why democratic breakthroughs were unsuccessful in two of these cases (Egypt and Yemen) from 2011–2012.

The authors challenge the earlier quantitative studies that suggest the primary explanations for post-transition democratization can be attributed solely to the role of opposition groups and political insiders during and after nonviolent protest campaigns. Specifically, Brownlee et al. (2015) dispute the claims that nonviolent protest campaigns alone insure that negotiation, compromise and dispersed power among groups will produce post-transition democracies. Instead, they believe that two pre-existing structural factors are critical for consolidating democracy: strong state institutions and pluralistic civic societies. While Yemen lacked both of these qualities which explains its failed democratization, Tunisia and Egypt had strong state institutions and strong enough civic societies to pressure armed forces to defect from the executive and compel incumbents to comply with popular demands for democratic elections. Despite these advantages, Egypt's pre-existing civic society was dominated by Islamic religious institutions that provided Islamic parties with enormous resources to mobilize their voters in the founding election. The result was an imbalance between Egypt's Islamic forces and secular groups within the new government. As the new government moved to solidify Islamic power in government institutions, secular groups protested and the military intervened with a coup. Tunisia, however, had a stronger (more pluralistic) pre-existing civic society that reflected a mix of powerful actors among labor unions, professionals' and women's organizations, as well as religious and other secular institutions – all of which were able to mobilize large voting blocs in the founding election. The result was a new government with cross-cutting cleavages among key constituencies. Consequently, democracy was far more durable in Tunisia than in Egypt. Of course, this story of comparative durability remains very much in play.

The takeaway from the research by Brownlee et al. (2015) on nonviolent protest campaigns, regime breakdown, and democratic transition and consolidation in the Arab Spring cases is that structural factors in society are more important to the survival of democracy than the characteristics of the campaigns themselves. We agree with their views, because another important structural factor involves the historical propensity of the military to ins ert itself in politics, especially during broad-based protest campaigns, which we believe also critically influences the trajectory toward or away from democratization.

4.

The Role of Military Intervention During

and After Nonviolent Protest Campaigns

Despite the success of nonviolent protesters in some countries in the Arab Spring, nonviolent civilian resistance campaigns overthrow governments less frequently than we realize. And, in cases wh ere it does happen, protesters often deserve less credit for the political changes that occur in the aftermath. Behind the scenes, the military is a critical player in the downfall or survival of autocratic regimes (Bellin 2012; Lutterbeck 2013; Droz-Vincent 2014; Pion-Berlin, Esparza, and Grisham 2014). Although sometimes soldiers may march in the streets or direct their tanks at a presidential palace, the military frequently plays a more covert role. Of course, the military has demonstrated that it has the capacity to overthrow regimes without civilian assistance. In these cases, military rebellion may be sufficient to cause the overthrow of dictators (and non-dictators). But, when large scale civilian resistance campaigns emerge and popular demands shift from narrow reforms to broader ones advancing government resignations, the military may be the pivotal player that actually brings about the removal of rulers. If the military pledges its support to a threatened regime, autocrats are more likely to remain intransigent and in office. If the military withdraws its support from a threatened regime, autocrats are more likely to be forced to capitulate.

One prominent student of revolution summarizes revolutionary prospects in the following way:

For a revolution to succeed, a number of factors have to come together. The government must appear so irremediably unjust or inept that it is widely viewed as a threat to the country's future; elites (especially in the military) must be alienated from the state and no longer willing to defend it; a broad-based section of the population, spanning ethnic and religious groups and socioeconomic classes, must mobilize; and international powers must either refuse to step in to defend the government or constrain it from using maximum force to defend itself. Revolutions rarely triumph because these conditions rarely coincide… (Goldstone 2011).

Barany stresses the role of the military even more and, in the process, advances both a generic and a specific Middle Eastern generalization:

No institution matters more to a state's survival than its military and no revolution within a state can succeed without the support or at least the acquiescence of its armed forces. This is not to say that the army's backing is sufficient to make a successful revolution; indeed, revolutions require so many political, social, and economic forces to line up just right, and at just the right moment, that revolutions rarely succeed. But support from a preponderance of the armed forces is surely a necessary condition for revolutionary success.

How a military responds to a revolution is the most reliable predictor of that revolution's outcome. When the army decides not to back the regime (Tunisia, Egypt), the regime is most likely doomed. Wh ere the soldiers opt to stick with the status quo (Bahrain, Syria), the regime survives. Wh ere the armed forces are divided (Libya, Yemen), the result is determined by other factors such as foreign intervention, the strength of the opposition forces, and the old regime's resolve to persevere (Barany 2011: 24, 32–33).

Thus, for all the very real dramas going on in the street and liberally captured by the media for global consumption, some of the real drama is not captured by the television cameras. Nonviolent civilian overthrows of governments are rarer than is typically thought to be the case. What are more common are the interactions between civilian protests and the loss of military support.[11] It follows that what happens after the regime falls is not solely a function of the demands of the civilian protestors. What the military wants is also likely to matter.[12]

We can state this a bit more strongly. The more the military is involved in government overthrows, the more likely they will become critical veto actors in determining the shape and direction that new regimes will take (Tusalem 2014). Nonetheless, strong military involvement does not guarantee some form of continued autocracy even though military institutions value order and stability. Governmental reforms will depend on a variety of factors including negotiations with civilian politicians, the nature of state-military-civic society interactions, and the degree to which military commanders can control their own troops.

The military can choose to ally with civilian politicians and parties that support the existing state or it may choose to respond to civilian demands for military intervention.[13] In the event of a regime downfall, a provisional, transitional junta may represent a coalition of civilian and military actors which determines if and how much political reforms take place. Alternatively, the military may take on the transitional responsibilities exclusively, either for a brief period or for an extended one. And, in some cases, military transitional regimes can transition further to civilian regimes led by a former high-ranking military figure who has been elected to office.

In addition, how militaries interact with civilians depends in part on what type of political role the military has played in the immediate past. For instance, after a prolonged period of military rule, the military may choose to surrender its political power voluntarily because its leaders have not ruled more successfully than their civilian predecessors. This sentiment is especially likely if there has been political-economic deterioration in the country during military rule. Lastly, the military may step down if staying in power threatens to irreparably damage the institution should internal disputes about how best to proceed threaten to fragment its command and control.

Transition outcomes are also dependent on the type of civilian-military relations that prevailed prior to the overthrow (Brownlee et al. 2015). Militaries can be highly professional, politically neutral organizations with little or no involvement in politics. The other extreme is that the armed forces – usually in the aftermath of a radical regime change effected by the military – are highly politicized and become one of the main pillars supporting the new regime. In between these two ends of the continuum are situations in which the military has a privileged position in society, acts as a major player in the economy and/or regime, but wh ere rulers may have created various types of coup-proofing arrangements. The latter include situations wh ere the regular military is supervised by ideological commissars or controlled by an ethnic minority that also controls the state. Or, the military may be out-gunned by national guards, party militias, or units controlled by the members of the ruler's family. In some cases, the regular military is simply not allowed to possess live ammunition.

Thus, when one invokes the ‘military’, we must recognize that military institutions and civil-military arrangements do not come in one convenient category. As noted by Barany (2011), strong and relatively autonomous military institutions are most likely to act as a unified organization, as seen in Egypt, wh ere the militaries decided not to defend the incumbent ruler. Weak and penetrated (e.g., ethnically dominated) military institutions are less likely to act or, if they do, they tend to support the incumbent regime, as in Syria. And, when these militaries act against the regime, it is more likely to be in a fragmented or non-hierarchical way – along the lines witnessed in Libya and Yemen.

Despite these variations and whether the military acts as a unified or fragmented actor, we are interested more broadly in the extent of the military involvement in situations wh ere civil resistance campaigns threaten the survival of national rulers. We argue that the more heavily involved the military is during the campaign, the more likely it is that its involvement will work against future democratization.[14] Our reasoning is based on the logic that democratization proceeds most readily in environments that facilitate its emergence and maintenance. Income inequalities, low economic development, social cleavages and illiteracy fail to facilitate democratization.[15]

Likewise, political systems in which the military are salient political actors also fail to support democratization (Tusalem 2014). Military politicians and military organizations in general have interests that are unlikely to prioritize democratization largely because it is not as salient as external defense, institutional welfare, domestic order and stability and personal ambitions. One last consideration is that military actors that are highly salient are also likely to reside in settings which hinder democratization processes. These settings are usually less developed and devoid of strong civic associations which can support oppositional mobilization. As societies become more economically developed and complex, the political salience of the military tends to recede.[16]

Nor do we wish to underestimate the role of civilian protesters in bringing down national rulers. Without broad-based protest campaigns involving dissidents demanding political change, we find it unlikely that incumbent regimes will step down. Protest campaigns create political opportunities that increase the likelihood of the fall of the regime. However, we argue that protest campaigns do not deserve all of the credit for regime changes. In fact, we believe that protest campaigns fail more often than they succeed. Other factors play important roles as well. For instance, protesters may not have the stamina or the willingness to sustain a large protest campaign beyond a few days. Regime rulers that are targeted may not be vulnerable due to strong alliances within and outside their ruling cliques. So long as they have access to adequate coercive forces to repress civilian protesters, rulers can survive and outlast protest campaigns.

Although scholars of nonviolent protest are well aware of the significance of the military's role, our impression is that they are inclined to acknowledge it but are unwilling to grant it any autonomous status.[17] To do so would detract from the efficacy of nonviolent protest and its implications for civilian/civil society and political power. Instead, they tend to treat the military's actions as a response to the tactics of protestors (nonviolent protests are less likely to provoke a military response, while violent protests invite it). We argue that the military's choices are an important independent factor in the outcomes of successful, as well as unsuccessful, protests. At the same time, we do not want to exaggerate the relative role of the military. We acknowledge that during the course of a protest campaign the military is part of a complex set of interactions between domestic and in some cases international actors. Hence, the military is not necessarily the only factor that determines the events during and after protest campaigns.

Accordingly, we propose to compare the relative strength of civilian protest with the role of the military in the outcomes of successful, nonviolent, regime transitions. We are not examining the factors that led to successful overthrows. Rather, we are interested in post-success outcomes. More specifically, whether or to what extent these transitions lead to more or less democratic political systems is the main question. Our argument is simple. The most salient political actors that bring about government transition will have a strong influence on the subsequent changes in that regime. We expect that democratic political changes are more likely to occur in the aftermath of protest campaigns that are broad in both their scale and scope of participation. We also expect that this outcome is less likely to happen in the event that the military plays a significant role during the course of the protest campaign. Although we are agnostic about whether broad-based protest campaigns or military involvement has a greater theoretical impact than the other, we do suspect that the extent of military involvement will have a stronger influence. Some 70 years ago, Chorley (1943[1973]: 20) wrote that ‘The rule then emerges clearly that governments... which are in full control of their armed forces and are in a position to use them to full effect have a decisive superiority which no rebel force can hope to overcome’.

On civilian uprisings, she also wrote that

The spontaneous mass uprising … goes forward by the sheer impetus of its own tremendous weight. … It has the qualities of the rising flood-tide or the mountain avalanche. At the same time it has the defects of these qualities. The tide turns from flood to ebb and the avalanche expends itself perhaps before any objective of real importance has been swept out of its track. Unless the spontaneous mass uprising can be captured and directed by competent leadership, it will end in failure. It may topple over a weak … [regime] but it will be unable to hold its gains (Chorley 1943[1973]: 40).

Chorley may have been overly pessimistic about mass uprisings but her point is that deploying armed forces against rebels is more likely to be successful than are the chances of mass uprisings to prevail, all other things being equal. We use a similar logic for expecting military involvement in nonviolent transitions to be at least as significant as the breadth of the popular revolt. There is no reason, of course, why both of them cannot be significant or why they cannot generate contradictory influences on what happens after governments fall.

One problem with examining successful, nonviolent, protest movements is a small sample size which restricts the degrees of freedom necessary for multiple variables to be examined simultaneously. Nonetheless, we believe that there are several rival hypotheses that need to be considered as well. One is the nature of the regime. Regime overthrows tend to involve autocracies that become less autocratic subsequently. We maintain that different types of autocracies will have different proclivities toward greater democratization. Geddes (1999a: 136), for instance, finds that military regimes have a 31 % likelihood of becoming more stable and democratic while personalist regimes have only a 16 % likelihood. The type of regime under attack, therefore, is a possible intervening variable.[18] At the same time, the distribution of wealth in political systems can play a role influencing greater democratization. Systems with higher average income levels are better able to sustain democratization, even if low average levels do not necessarily deter attempts to democratize (Przeworski et al. 2000).

The Cold War is another possible intervening variable (Nepstad 2011). Superpowers frequently supported military regimes (and their domestic intervention in mass uprisings) in order to uphold a global and local status quo. Therefore, the question is whether military involvement in nonviolent protest campaigns and more autocratic post-transition regimes were more likely to occur during the Cold War than afterwards (e.g., post-1988). Finally, different regions will also have variable tendencies toward supporting democratization efforts. Europe, for instance, possesses a number of states that are already highly democratic and has relatively strong international organizations (the European Union, NATO) that can be used to encourage democratization. Moreover, valued NATO membership can be withheld if a new regime fails to meet certain regional expectations of democratization. Beyond Europe, other regions are more autocratic than democratic and hence, they lack the organizational vehicles that can promote favored outcomes. We believe that a state in the Middle East is more likely to remain autocratic after a protest campaign than one that is located in Europe. In short, regional influences may be an important factor on regime changes.

5. Research Design and Methodology

5.1. Sample

Our cross-national sample for nonviolent protest campaigns that had successful outcomes is derived from Nepstad's list (2011: xv) which yielded 20 cases between 1978 and 2005.[19] We then supplemented this list with an additional 16 successful cases that are found in Chenoweth and Stephan's (2011: 233–236) list of nonviolent campaigns. Despite the reliance on two data lists, there is a great deal of agreement between Nepstad and Chenoweth and Stephan on what nonviolent protest campaigns represent. Nepstad defines her cases as citizen uprisings or civilian resistance against local regimes and rulers. These revolts involve mostly nonviolent tactics, such as demonstrations, protests, boycotts and strikes. Because these cases yielded successful overthrows of sitting governments, Nepstad refers to them as ‘nonviolent revolutions’. However, we prefer Chenoweth and Stephan's concept of ‘nonviolent civil resistance campaigns’, because it avoids the question of just what a ‘revolutionary outcome’ actually means and it avoids entangling the causes of outcomes from those that bring about civil resistance campaigns in the first place.[20] For Chenoweth and Stephan, a nonviolent civil resistance campaign is ‘a series of observable, continual, purposive mass tactics in pursuit of a political objective’ (Ibid.: 14). These campaigns can last days or years; they are likely to have leadership; they have relatively clear beginnings and endings; and they involve political actions that involve non-institutional (and frequently illegal) anti-regime tactics (e.g., boycotts, sit-ins, protests, strikes, and demonstrations).[21] Fortunately, Nepstad's 20 cases that formed the original core of our sample are also found in Chenoweth and Stephan's list of nonviolent civil resistance campaigns. Since we are only interested in nonviolent civil resistance campaigns that lead to changes in governments, we found additional 16 post-1945 cases in the Chenoweth-Stephan list that are compatible with our original 20 cases.

Despite their agreement about the criteria for nonviolent civil resistance campaigns, Nepstad and Chenoweth and Stephan diverge a little on how they define whether these campaigns were successful. Nepstad (2011: xiii) employs a very simple criterion: success is the removal of an existing regime or ruler. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011: 14) maintain that a campaign is successful if it meets two criteria: a) the campaign achieves its stated goals within a year of its peak activities, and b) the campaign has a discernible effect on an outcome and the outcome is a direct result of the campaign (e.g., regime change). Despite these differences, Nepstad's cases of success are identical to Chenoweth and Stephan's coding for success in these 20 overlapping cases. Therefore, our sample is composed of 36 cases of nonviolent civil resistance campaigns that had successful outcomes, all of which were associated with regime change. In this situation, we adhere to Nepstad's definition of success.[22]

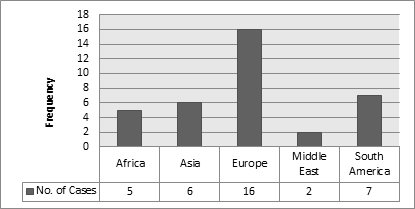

These cases are shown in Table 1.[23] Our sample includes cases as early as 1958 and as late as 2005. Ten of the 36 cases began in 1989 and ended by 1992, and six of these cases are associated with popular revolts against Soviet-supported non-democratic governments in Eastern Europe. The bar chart in Fig. 1 shows that almost half of the 36 cases occurred in Europe with South America providing the next highest number of cases with seven campaigns. Africa, Asia and the Middle East provide the remaining 13 cases.[24]

Table 1. Nonviolent Protest Campaigns with Successful Outcomes, 1974–2005

|

Beginning

|

Ending Year |

Campaign Name If Available |

Location |

|

1958 |

1958 |

|

Venezuela |

|

1960 |

1960 |

Student Revolution |

South Korea |

|

1974 |

1974 |

Carnation Revolution |

Portugal |

|

1974 |

1974 |

|

Greece |

|

1977 |

1979 |

Iranian Revolution |

Iran |

|

1977 |

1981 |

Pro-Democracy Movement |

Argentina |

|

1981 |

1989 |

Solidarity |

Poland |

|

1983 |

1989 |

|

Chile |

|

1983 |

1986 |

|

Philippines |

|

1984 |

1994 |

Anti-Apartheid |

South Africa |

|

1984 |

1985 |

Diretas Ja |

Brazil |

|

1984 |

1985 |

|

Uruguay |

|

1985 |

1985 |

|

Haiti |

|

1985 |

1985 |

|

Sudan |

|

1989 |

1989 |

Singing Revolution |

Estonia |

|

1989 |

1989 |

Pro-Democracy Movement |

Latvia |

|

1989 |

1991 |

Pro-Democracy Movement/Sajudis |

Lithuania |

|

1989 |

1992 |

|

Mali |

|

1989 |

1989 |

Velvet Revolution |

Czechoslovakia |

|

1989 |

1989 |

Pro-Democracy Movement |

East Germany |

|

1989 |

1989 |

Pro-Democracy Movement |

Hungary |

|

1989 |

1992 |

People Against Violence |

Slovakia |

|

1989 |

1990 |

|

Slovenia |

|

1989 |

1989 |

|

Bulgaria |

|

1991 |

1993 |

Active Voices |

Madagascar |

|

1997 |

1998 |

|

Indonesia |

|

1999 |

2000 |

|

Croatia |

|

2000 |

2000 |

|

Serbia |

|

2000 |

2000 |

|

Peru |

|

2001 |

2004 |

Orange Revolution |

Ukraine |

|

2001 |

2001 |

Second People Power Movement |

Philippines |

|

2001 |

2001 |

|

Zambia |

|

2003 |

2003 |

Rose Revolution |

Georgia |

|

2005 |

2005 |

Cedar Revolution |

Lebanon |

|

2005 |

2005 |

Tulip Revolution |

Kyrgyzstan |

|

2005 |

2005 |

|

Thailand |

Source: Nepstad 2011; Chenoweth 2011.

Fig. 1. Protest campaigns by region variable measures

5.2. Five- and Ten-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Levels

We are interested in whether regimes become more democratic after governments are brought down by civilian protests. A straightforward approach is to ask how democratic a post regime transition is shortly after an overthrow (five years) and then a little longer down the road (ten years). The two dependent variables in this analysis are derived from Polity II scores denoting the level of democratization in each location wh ere a protest campaign occurred. The Polity II scores are obtained from Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) which were derived from the Polity IV dataset[25]. We identify the democratization level in each location for a protest campaign five years after the campaign has ended for a short-term observation on the democratization score. The ten-year post-campaign Polity II score for each case reflects a potentially longer-term effect on democratization. The variation of these two variables is shown in Table 2. We find that on a cross-national basis these two post-campaign democratization variables are correlated at 0.96 despite losing five cases in the ten-year post-campaign sample (i.e., Ukraine 2001; Georgia 2003; Lebanon 2005; Kyrgyzstan 2005; Thailand 2005). Ideally, we would have preferred to calculate a change in the democratization level for each location, comparing the pre-campaign level with the post-campaign democratization levels five and ten years later. Unfortunately, the changes in these cross-national democratization variables show little variation because the within-country differences are quite small. Hence, the restricted variance for the overall democratization change variables undermines our regression models. Nonetheless, we did correlate, on a cross-national basis, a democratization variable that is based on the democratization scores for each location one year prior to a protest campaign with our two indicators for five- and ten-year post-campaign democratization levels. We found that the correlations between these variables are quite low. For instance, the correlation between the democratization variable one year prior to the protest campaign with the democratization variable five years after the campaign is 0.17, while the correlation between the pre and ten year post-campaign democratization variables is 0.18. These low correlations indicate that on an absolute level, there are significant differences in the democratization scores prior to and after the successful protest campaigns cross-nationally. In short, there is movement in the democratization levels five and ten years later across the sample.

Table 2. Variation of key variables in OLS regression models

|

|

Extent |

Peak Membership |

Five-Year Post-Campaign Democratization |

Ten-Year Post-Campaign Democratization |

GDP Per Capita |

Democratic Neighborhood |

|

Mean |

2.92 |

347,431 |

6.44 |

6.65 |

5,131 |

402 |

|

Median |

2.00 |

150,000 |

7.50 |

8.00 |

5,158 |

333 |

|

Maximum |

5.00 |

2,000,00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

10,820 |

1 |

|

Minimum |

0.00 |

2,500 |

–5.20 |

–5.40 |

665 |

0 |

|

Std. Dev. |

1.53 |

500,196 |

3.87 |

4.22 |

3,028 |

299 |

|

Observations |

(36) |

(36) |

(36) |

(31) |

(36) |

(31) |

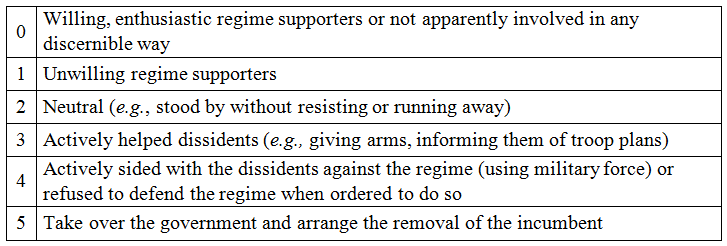

5.3. Extent of Military Defection

This independent variable is an ordinal measure of the degree of disloyalty among the armed forces and varies between 0 and 5, with 5 representing the highest level of military defection. Each of the 36 protest campaigns were studied to determine which value was most appropriate for each case. The variable itself reflects the following scale[26]:

Table 3. Variation Degree of Military Disloyalty

5.4. Peak Membership

Peak membership is an important variable, because Chenoweth and Stephan (2011: 39–45) maintain that in the context of nonviolent protest campaigns large participation levels are highly correlated with successful outcomes for several reasons. First, excessively large mass mobilizations indicate that a broad segment of society is engaged and this diversity makes it harder for governments to repress the public without generating a backlash effect that escalates the scale and scope of future protests. Hence, governments are careful about adopting indiscriminate repressive violence to demobilize protesters. The unintended consequence is that bystanders join the protesters as the perceived costs of protesting declines. Another reason that peak membership is likely to be highly correlated with success is the presence of dense and overlapping social networks that sustain participation, encourage innovative tactical diversity, and insure a unified opposition around shared goals and strategies. Consequently, mass participation and nonviolent disruptive action enhance the leverage that the public has vis-à-vis governmental adversaries by directly pressuring institutional allies and third parties to withdraw their support and bring about governmental reforms.

We obtain a peak membership count variable from Chenoweth and Stephan's (2011) dataset. Peak membership is determined by the highest number of participants reported to have been engaged in protest activity at any single time during the course of the campaign.[27] Chenoweth and Stephan rely on estimated counts provided by numerous encyclopedic and open sources to generate these participation figures.[28] Table 2 shows that the variation from the low to high levels of peak membership is skewed to the larger sizes. Hence, logged peak membership will be used for the subsequent regression models.

5.5. Economic Development, Authoritarian Regime Types, the Cold War and Regional EffectsPrevious research also shows that transitions to democracy are likely to be influenced by several other variables. For instance, higher income countries are likely to be positively associated with greater changes in democratization than poorer ones; certain types of authoritarian regimes (e.g., military governments) are more likely to transition to democracies while other types (e.g., single party and personalist governments) are less likely (Geddes 1999a); and finally, governments could have been less likely to shift toward greater democratization during the Cold War. We also need to consider regional influences since 44 % of our sample is derived from European cases.

Economic development will be measured as the real GDP per capita in the year prior to each case of a protest campaign.[29] Type of authoritarian government is operationalized as a single party, military or personalist government based on Geddes' definition. Each type is represented in the regression models below as dummy variables.[30] The government designations were applied to those locations in the year prior to each protest campaign case. The Cold War is represented as a dummy variable which is coded 1 for those protest campaigns that began before 1989 and 0 for the remaining cases. Finally, the European cases in the sample were represented as 1, while the others are designated as 0. We also include a measure for the neighborhood effects of democracy. When states reside in highly democratic regions, one can expect that governments will transition to democracy successfully. We rely on a measure used by Celestino and Gleditsch (2013) that calculates the proportion of neighboring states that are democracies within 500 km of a state's borders.

6.

Bivariate Correlations Among Independent

and Dependent Variables

Unfortunately, the limited sample size makes it impossible to estimate our key variables of interest while controlling for income, regime type, the Cold War and region in a single regression model. One possible solution would be to expand the sample to include other types of internal revolts or include cases that had both successful and unsuccessful outcomes. For instance, we could expand the sample to include violent as well as nonviolent episodes of internal revolt that were associated with successful outcomes. However, most of the violent cases that we observe in the Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) data involve low-intensity asymmetrical or guerrilla warfare which we believe are not equivalent to protest campaigns. Participants in protest campaigns are usually demonstrating peacefully and if violence occurs, it is the outcome of clashes between local security forces and the participants, as the government tries to demobilize the protesters. In cases of asymmetrical warfare, rebels are recruited and organized along military lines with the intention of waging war against the government, colonial or foreign occupation forces. Although both situations are instances of internal revolts, we do not think that the presence or absence of violence is enough to make them comparable. Another possible way to extend the sample would be to include protest campaigns that ended in failure. If our research question centered on why some campaigns were more successful than others, this would be a viable strategy. However, we are interested in comparing the impact of success on future levels of governmental change, for example, greater democratization. Since we assume that failed protest campaigns are less likely to produce governmental changes, we prefer to focus on the successful campaigns.

The downside to maintaining cross-national equivalence is dealing with a small sample size, especially when the key variables under investigation – peak membership and extent of military defection – are likely to be correlated with other variables that we would like to control for. Hence, our ability to estimate a single regression model is severely hampered. Therefore, we will opt for a simple strategy that involves estimating several regression models for both the short- and long-term democratization level. This means that in some of our models, one of our independent variables of interest is not likely to be estimated in the presence of another highly collinear control variable.

Table 3 provides the bivariate correlations among the post-five year democratization dependent variable, and the independent variables of extent of military defection, peak membership and the remaining control variables.

Table 3. Bivariate Correlations Between Five-Year Democracy and Independent Variables (N = 31)

|

Five- Year Democracy |

Military Defection |

Logged Membership |

GDP per capita |

Military Regime |

Prop. Dem. Neighbors |

Personalist |

Single Party |

Europe |

|

|

Five-Year Dem. |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Defection |

–.23 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L. Membership |

.07 |

–.15 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GDP/pc |

.49 |

–.21 |

.07 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military Regime |

.16 |

–.15 |

–.28 |

.30 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Democratic Neighbors |

.17 |

–.16 |

.14 |

.25 |

–.17 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

Personalist |

–.15 |

.68 |

–.12 |

–.32 |

–.23 |

–.20 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Single Party |

.27 |

–.38 |

.02 |

.30 |

–.19 |

.21 |

–.10 |

1.00 |

|

|

Europe |

.35 |

–.20 |

–.05 |

.41 |

–.08 |

.33 |

–.28 |

.49 |

1.00 |

|

Cold War |

–.28 |

.13 |

–.03 |

.19 |

.45 |

–.13 |

.09 |

–.25 |

–.38 |

Table 4. Bivariate Correlations Between Ten-Year Democracy and Independent Variables (N = 26)

|

Ten Year Democracy |

Military Defection |

Logged Membership |

GDP per capita |

Military Regime |

Prop. Dem. Neighbors |

Personalist |

Single Party |

Europe |

|

|

Ten-Year Dem. |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Defection |

–.38 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L. Membership |

–.01 |

–.15 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GDP/pc |

.50 |

–.34 |

.07 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military Regime |

.23 |

–.17 |

–.29 |

.33 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Democratic Neighbors |

.22 |

–.21 |

.09 |

.28 |

–.21 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

Personalist |

–.21 |

.74 |

–.11 |

–.33 |

–.28 |

–.25 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Single Party |

.29 |

–.43 |

.04 |

.34 |

–.23 |

.21 |

–.17 |

1.00 |

|

|

Europe |

.40 |

–.25 |

–.11 |

.50 |

–.09 |

.28 |

–.31 |

.56 |

1.00 |

|

Cold War |

–.20 |

.13 |

.01 |

.22 |

.43 |

–.21 |

.00 |

–.37 |

–.24 |

7. OLS Regression Models

We estimate two ordinary least square regression models for the five- and ten-year post-campaign democratization dependent variables and our key variables of interest – extent of military defection and logged peak membership. We will also estimate similar regression models that exclude one of these key variables in the event that one of them is highly collinear with the control variables of income, regime type, region, proportion of democracies in the neighborhood and Cold War. In addition to our key independent variables of extent of military defection and logged peak membership, we introduce dummy variables to control for three outliers (Iran, Haiti and South Korea).[31]

(a) Y1 (Five-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level) = β0 + β1 (Extent of Military Defection)t + β2 (Logged Peak Membership)t + β3 (Iran)t + β4 (Haiti)t + β5 (South Korea)t + ε0

(b) Y1 (Ten-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level) = β0 + β1 (Extent of Military Defection)t + β2 (Logged Peak Membership)t + β3 (Iran)t + β4 (Haiti)t + β5 (South Korea)t + ε0

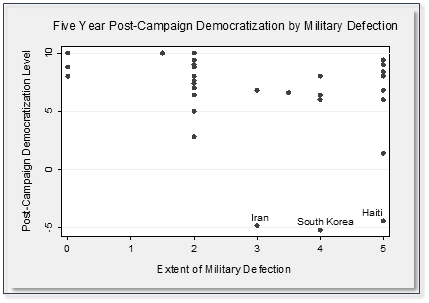

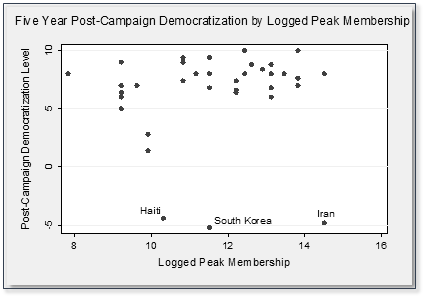

Fig. 2. Scatterplots of Five-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level by Military Defection and Peak Membership (N = 36)

Fig. 2 demonstrates the outlier problems in the bivariate scatterplots between the independent variables and the five-year post-campaign democratization variable. While the bivariate correlation between logged peak membership and the five-year post-campaign democratization variable is –0.07 in the presence of these three outliers, this correlation becomes 0.23 when we exclude the outliers.[32] We are reluctant to drop at least two of these outliers (Haiti and South Korea), because these cases behave according to our hypothesized relationships. In both cases, the extent of defection is high (5 in Haiti and 4 in South Korea), while the democratization levels for both the five- and ten-year post-campaign periods are among the lowest in the sample. Nonetheless, their extreme scores may bias the regression outcomes in favor of the defection variable. The Iranian case, however, is distinctly different. While defection level has a middling value (3), peak membership participation is the highest in the sample. Meanwhile, the Iranian democratization levels for both five- and ten- year post-campaign periods are among the lowest scores in the sample. Hence, the Iranian case does not behave according to our theoretical expectations. Since we have a small sample, deleting cases may undermine the validity of our findings. Therefore, we have opted to fit these cases with a dummy variable as a con-servative strategy.

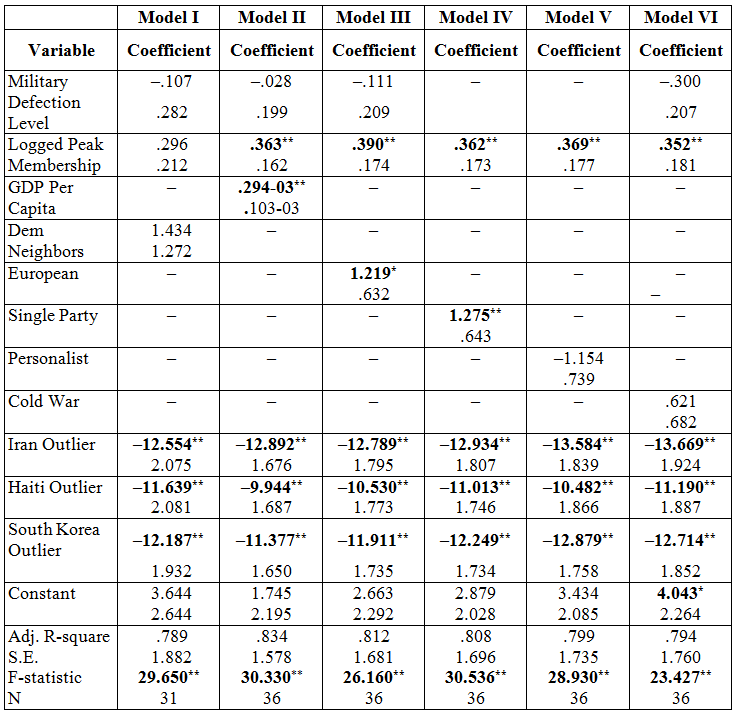

8. Results

The OLS regression estimates are provided in Table 5. In the short term (the five-year post-campaign democratization outcome), logged peak membership is statistically significant and in the correct positive direction in five of the six models with the exception of Model I wh ere the proportion of democratic neighbors is present. Meanwhile, the extent of military defection is not statistically related to democratization level in the four models in which it appears but in all cases it is negatively signed as expected. As for the remaining variables, Table 5 shows that GDP per capita has a strong positive relationship to the democratization outcome (see Model II); that single party regimes and Europe are also positive and significantly related to democratization level (see Models III and IV); that personalist authoritarian regimes have a weak but negative effect on democratization (Model V); and finally, that the Cold War is unexpectedly positively but weakly related to democratization (Model III). The Cold War estimate is problematic because the bivariate correlations show that Cold War cases are negatively related to the two dependent variables. The bivariate scatter plots also indicate that the mean level of democratization is lower for the Cold War cases, and a bivariate regression model also shows that the Cold War is negatively related to both democratization variables. Yet, in a multivariate regression model, the estimates are positive. We believe that the small samples, the outliers, and the degree of correlation between Cold War and the defection variables have combined to produce a biased estimate with the wrong sign.

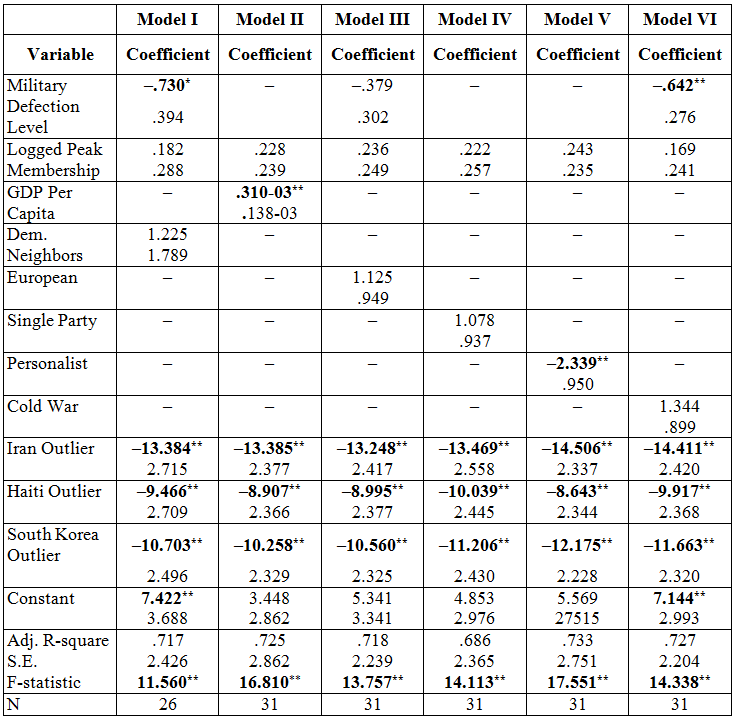

Table 6 presents the results for a ten-year look at democratization levels. In this case, the extent of military defection is strongly and negatively related to democratization in two of the regression models (Models I and VI). Meanwhile, peak membership is positive but weakly related in all of the six models. These results reverse the pattern that we observe in the five-year post-campaign democratization level. Meanwhile, GDP per capita continues to have a strong positive relationship to democratization. Unlike the five-year democratization outcome results, personalist regime has a strong negative influence on democratization (Model V). The Cold War coefficient is estimated in the wrong direction and depicts the same problem for the earlier regression model in Table 4.

Considering the small sample sizes in both Tables 5 and 6, we are less interested in the level of statistical significance than we are about understanding the nature of the impact of the independent variables on post-campaign democratization variables. Hence, we derive the predictive probability estimates based on our earlier models and we include the results for the statistically significant coefficients in Table 7. We expect to observe that the shift from the baseline estimate of our two dependent variables will be negative for the extent of military defection as hypothesized, while we expect that there will be a positive shift from the baseline estimate of the dependent variables in the presence of logged peak membership. Meanwhile, the remaining variables are also expected to have a positive increase in the dependent variables with the exception of personalist regime which is expected to be negatively related. These directional relationships are indeed reflected in the Clarify-derived results. In the short term, we observe that GDP per capita has the strongest impact on democratization five years after a protest campaign with a 26 % increase, followed by peak membership with a 16 % increase, single party regime with a 14 % increase and finally, the Europe cases were associated with an 11 % increase.

As for the longer-term influence of the independent variables on democratization level ten years after a protest campaign, Table 7 shows a very different pattern. In this situation, peak membership is not included since its regression coefficient across six models failed to be statistically significant. Meanwhile, extent of military defection leads to a strong 20 % decline in democratization, which is a strong contrast to its lack of statistical significance for the five-year democratization variable. GDP per capita continues to exert the same influence on democratization ten years after in comparison to its influence for the five-year democratization level. Lastly, personalist regimes are associated with a 26 % decline in the long-term level of democratization.

Table 5. Estimates of OLS Models for Five-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level

Although the samples are small, which may decrease the reliability of the findings, we believe that in this cross-national study, the results have important implications. For instance, a large broad-based coalition of protesters has an impact on increasing democratization levels within five years of a protest campaign. However, this outcome appears to be mitigated by the role that the military plays in the longer post-campaign period. The findings suggest that despite shifts in democratization levels in the short term, the role of the military is more important in the longer term. In other words, short-term gains achieved by nonviolent civil resistance campaigns may be offset by long-term losses due to the continuing involvement of the military, which as an institution is unwilling to support and maintain deep democratization changes.

Table 6. Estimates of OLS Models for Ten-Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level

Note: Standard errors are reported below coefficients. *p < = .10; **p < = .05.

9. Conclusion

Unfortunately, nonviolent civilian protest campaigns that overthrow governments are not sufficiently common to facilitate problem-free statistical analysis. Nearly half of all the cases have taken place in the one region most likely to facilitate democratization and least likely to be characterized by strong military involvements. Nonetheless, some improvement in democratization is usually generated by successful political transitions of this type, but the type of regime that is overthrown clearly makes some difference as well. Still, our investigation of the protest campaigns that have occurred between 1945 and 2006 provide respectable empirical support for our basic propositions. The size, scale and scope of nonviolent protest campaigns matter but they appear to matter most for immediate, shorter-term changes in the direction of greater democratization. The extent of military involvement also matters but its influence is manifested more strongly in a slightly longer-time frame, and in a negative direction.

What do these findings tell us? One strong implication is that nonviolent civilian protest campaigns that overthrow regimes represent complex sets of interactions among domestic and international actors. Protest campaigns can certainly bring down regimes, but in most cases, only if the military permits it. When the military is least involved in toppling the regime, the new subsequent regime is likely to be more democratic in the longer term. However, if the military is highly involved, the nature of the new regime is predictably less democratic in the long run, even if democratization does occur in the first few years. In short, despite the drama and suspense associated with large-scale protest campaigns, a considerable proportion of the most significant political activity is taking place behind the scenes and after the initial regime change. What will the military do when civilian protests swell and threaten an autocratic regime's survival? What will the military do after it has collectively abstained from providing the regime with any coercive support? What will the military do after it has overtly joined the rebellion against the incumbent regime?

Table 7. Post-Estimation Predictive Probabilities for Five- and Ten- Year Post-Campaign Democratization Level

|

Post CampaignTime Period |

Variable |

Expected

Y |

95

% |

%

Change from |

|

aFive-Year Democratization Level |

Logged Peak Membership |

7.485 |

6.392, 8.577 |

+16 |

|

GDP Per Capita |

8.116 |

6.800, 9.431 |

+26 |

|

|

European Region |

7.122 |

6.203, 8.042 |

+11 |

|

|

Single Party Regime |

7.365 |

6.254, 8.476 |

+14 |

|

|

bTen-Year |

Extent of Military Defection |

5.107 |

3.384, 6.831 |

–20 |

|

GDP Per Capita |

8.385 |

6.590,10.179 |

+26 |

|

|

Personalist Regime |

4.919 |

3.366, 6.506 |

–26 |

Notes:

a) Predictive Values for peak membership and GDP/per capita are derived from Model II (Table 5); for Europe and Single Party Regime, predictive values are derived from Models III and IV respectively (Table 5).

b) Predictive Value for Extent of Defection is derived

from Model 1 (Table 6); for peak membership and GDP/pc, predictive values are

derived from Model II (Table 6), and

for Personalist Regime, Model 5 (Table 6) is used.

c) Percentage change values of Y are derived from baseline estimates of Y wh ere X variables are held at their mean level for the appropriate OLS models in Tables 5 and 6. All of the estimated values of Y in the baseline models fell within a 95 % confidence interval. Baseline value for Y = Five Yr. Change in Democratization = 6.444; Baseline Values for Y = 10 Yr. Change = 6.360 (Model I) and 6.645 for remaining models.

Our findings suggest that military involvement tends to pull in the opposite direction than that of civilian reformers. This may not happen all the time. But, what seems most remarkable to us is that we know much more about the waxing and waning of civilian protest campaigns than we do about why militaries do what they do. One obvious reason is that the political involvement of the military is often more covert than the civilian protests that occur publically in the main square. A second reason is that getting access to military decision-makers for the purpose of probing their motives is difficult. Yet, the main reason for knowing less than we should is our tendency to view nonviolent civilian protest campaigns through rose-colored lenses. While we do not want to take anything away from the awesome spectacle that civilian resistance to autocratic regimes provide, we still need to acknowledge that other factors and processes are present. Sometimes, the protests in the streets are not wh ere the action that determines the most lasting impact happens to be.

References

Abrahamian E. 2011. Mass Protests in the Iranian Revolution, 1977–1979. Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Nonviolent Action from Ghandi to the Present / Ed. by A. Roberts, and T. G. Ash. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ackerman P., and Duvall J. 2000. A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Ackerman P., and Karatnycky A. (Eds.) 2005. How Freedom is Won: From Civic Resistance to Durable Democracy. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

Albrecht H., and Koehler K. 2020. Revolutionary Mass Uprisings in Authoritarian Regimes. International Area Studies Review 23(3): 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2233865920909611

Albrecht H., and Ohl D. 2016. Exit, Resistance, Loyalty: Military Behavior During Unrest in Authoritarian Regimes. Perspectives on Politics 14(1): 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592715003217

Alexander R. 1964. The Venezuelan Democratic Revolution. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Allen P. M. 1995. Madagascar: Conflicts of Authority in the Great Island. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Almeida P. 2008. Waves of Protest: Popular Struggle in El Salvador, 1925–2005. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Arcenaux C. L. 1997. Institutional Design, Military Rule, and Regime Transition in Argentina (1976–1983). Bulletin of Latin American Research 16: 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3050(96)00025-3

Argentieri F. 2008. Hungary: Dealing with the Past and Moving into the Future. Central & East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy / Ed. by S. L. Wolchik, and J. L. Curry, pp. 215–232. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Aslund A., and McFaul M. 2006. Revolution in Orange: The Origins of Ukraine's Democratic Breakthrough. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Barany Z. 2011. The Role of the Military. Journal of Democracy 22(4): 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2011.0069

Baskin M., and Pickering P. 2008. Former Yugoslavia and Its Successors. Central & East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy / Ed. by S. L. Wolchik, and J. L. Curry, pp. 281–316. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Bayer M., Bethke F. X., and Lambach D. 2016. The Democratic Dividend of Nonviolent Resistance. Journal of Peace Research 53(6): 758–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316658090

Beissinger M. R. 2002. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bellin E. 2012. Reconsidering the Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Lessons from the Arab Spring. Comparative Politics 44(2): 127–149. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/deref/http%3A%2F%2Fdx.doi.org%2F10.5129%2F001041512798838021.

Bidelux R., and Jeffries I. 2006. The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. London: Routledge.

Bresnan J. (Ed.) 1986. Crisis in the Philippines. The Marcos Era and Beyond Bresnan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brooks R. 2013. Abandoned at the Palace: Why the Tunisian Military Defected from the Ben Ali Regime in January 2011. Journal of Strategic Studies 36(2): 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2012.742011

Brooks R 2017. Military Defection and the Arab Spring. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. URL: https://oxfordre.com/politics.

Brownlee J., Masoud T., and Reynolds A. 2015. The Arab Spring: Pathways of Repression and Reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruszt L., and Stark D. 1992. Remaking the Political Field in Hungary: From the Politics of Confrontation to the Politics of Competition. Eastern Europe in Revolution / Ed. by I. Banac, pp. 15–55. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Budryte D. 2005. Taming Nationalism? Political Community Building in the Post-Soviet Baltic States. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Bueno de Mesquita B., Smith A., Siverson R., and Morrow J. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bugajski J. 2008. Bulgaria: Progress and Development. Central & East European Politics: From Communism to Democracy / Ed. by S. L. Wolchik, and J. L. Curry, pp. 361–404. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Burggraaff W. J. 1972. The Venezuelan Armed Forces in Politics, 1935–1959. London: Taylor and Francis.

Celestino M. R., and Gleditsch K. S. 2013. Fresh Carnations or All Thorn, No Rose? Nonviolent Campaigns and Transitions in Autocracies. Journal of Peace Research 50(3): 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022343312469979