The Feasibility of Matching the Taliban's Sharia-Based Order with Davis's Theory of the Sacred Society

скачать Авторы:

- Mohammad Abedi Ardakani - подписаться на статьи автора

- Seifabadi, Mohsen Shafiee - подписаться на статьи автора

Журнал: Social Evolution & History. Volume 24, Number 1 / March 2025 - подписаться на статьи журнала

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2025.01.06

Mohammad Abedi Ardakani, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran

Mohsen Shafiee Seifabadi, Ardakan University, Yazd, Iran

ABSTRACT

The Taliban*, in its two governments (1996–2001 and after August 2021), tried to establish an order based on religious laws and principles. The main question in this regard is whether or not this order is based on any theoretical framework. Apparently, among the various existing theories, the Taliban's Sharia-based order is more akin to Davis's theory of the ‘sacred society’. Hence, by drawing on a theoretical framework the principal elements of which are proposed by Davis, this article seeks to assess the Sharia-based order of the Taliban and its social aftermaths and to compare them with Davis's sacred society. The second question to answer is whether the Taliban's intended order accords with Davis's sacred society. The results show that, in their second term of governance, the Taliban strived to conduct actions deemed ‘abnormal’ by the international community with greater caution and gentleness, but they continue to pursue the same goals and methods as during their first regime. This involves opposing modern norms and values accepted by the international community. Research findings suggest that, while the characteristics described by Davis for his traditional and reactive sacred society largely match those of the society under the Taliban rule in both periods of their governance, there are notable differences in detail.

Keywords: Afghanistan, Davis, sacred society, Sharia-based order, the Taliban*.

1. INTRODUCTION

Talibanism is a politico-ideological movement that emerged as a reaction to the inability of the Mujahideen government, led by Burhanuddin Rabbani, to establish a widely accepted political system. After capturing Kabul in 1996, the Taliban seized the power fr om the Mujahideen warlords in Afghanistan. Their motto was to ‘enforce Islamic Sharia and to stamp out corruption and sins’. In their rule, they showed a very strict facet of Islamic Sharia, rooted in their specific religious interpretations and Pashtun tribal traditions. Their state was short-lived, overthrown by the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

Twenty years later, however, in August 2021, they managed to return to power by recapturing Kabul and ousting the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Throughout both regimes, the Taliban aimed to establish a centralized and authoritarian system referred to as the ‘Islamic Emirate*,’ characterized by a Sharia-based order.

During their second tenure, the Taliban returned to power twenty years after their first rule. During this interim period, the administrations of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani, backed by the U.S. and its allies, implemented economic, political, and cultural reforms, achieving notable successes in areas such as the establishment of modern state organizations, elections, freedom of the press and women's rights, more than ever before in the country's history. Despite these advances, their governments ultimately failed and collapsed, demonstrating the challenges a traditional society like Afghanistan faces in establishing and expanding modern institutions.

Given the above considerations, there appears to have been little significant change in the Taliban's goals and methods in their second term compared to their first term. The same inflexibility observed during their first rule persists. However, based on their previous experience of governance, rather than fr om an ideological stance, the Taliban recognize the need to engage cautiously and meticulously with Afghan society and its citizens in order to gain the international support and legitimacy crucial to their survival.

This study aims to clarify whether the Taliban's Sharia-based rule in their first and second governments can be interpreted under Davis's definition of the sacred society. Accordingly, the primary question of this study is whether this rule fits Charles Davis's definition.

The importance of addressing this question lies in the need for the international community to understand whether the Taliban's Sharia-based order can adapt to international norms and values and embrace modern civilization, or whether it will persist in its opposition to them. If the latter continues, the Islamic Emirate is likely to face significant challenges and lose the chance for international recognition and membership in the global community. Thus, this research serves as a test to evaluate the critical issue of the struggle between ‘tradition and modernity’ and the ‘socialization of modern renewal versus the Taliban's Sharia-based order’. Ignoring the outcome of this struggle is not an option for any individual, state, organization, or institution.

2. METHODOLOGY

This study is descriptive-analytical and adopts a comparative qualitative approach. Although comparative studies are various in forms, this study is based on the ‘Pattern Matching’ method first coined by Donald Campbell in 1970. The method relates the data to the theory, and the hypothesis is that there is one pre-existent theoretical pattern about an important given problem or event. In other words, there is a theory or a set of theories about a given problem or event that suggest and predict patterns. Considering the facts, it is then assessed whether the problem or event in question fits this theoretical pattern, or whether the problem or event has occurred in accordance with this pattern. On the basis of this method, one can determine whether the problem or event follows or matches the expected pattern (Chalabi 2007: 21–22). In this respect, the main goal of the research is to determine whether Davis's theory of the sacred society matches the Sharia-based rule of the Taliban in the two periods of their power in Afghanistan and whether it has such a capability.

3. THE BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

There are several studies conducted on the sacred society, religious rule and chaotic conditions in Afghanistan. The latter subject addresses the attitudes and behavior of the Taliban. However, no research has been conducted using the approach of this study. So far, only a few researchers have employed Davis's theory of the sacred society. For example, Zakeri (2020) in an article entitled ‘The Sacred and the Moral in Post-revolutionary Society: Desacralized Sacred’, Mohadessi (2019) in the book God and Street, Zahed (2015) in the book Existence and the Sacred Thing, Shariati and Zakeri (2015) in an article entitled ‘The Status of Religion in Iran: Desacralized Sacred’, Aref Hosseini (2008) in the book The Sacred Utopia: A Criticism of the Four Patterns of Utopia set by Western Thinkers Compared with the Islamic Utopia of Mahdi, and Mohammadi (1998) in the book Following the Sacred, in Love with the Secular: An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion in Iran have tried to analyze the process of secularization in Iran with all its ups and downs. Each, in their own way, has attempted to determine the relationships between the secular and the sacred things in Iran, especially after the Islamic Revolution. While these attempts are in some ways consistent with Davis's theory of the sacred society, they depart fr om his generalizing theory by being specific to Iran.

On the other hand, many research works have been conducted on the traditional Afghan society and the Taliban with a particular outlook about the situation. In his article ‘Afghanistan: The Shifting Religious Order and Islamic Democracy’, Anwar Ouassini (2018) assesses the relationship between the religious system and the newly-formed democratic organizations in Afghanistan. He argues that the legitimation of the political sphere by the Islamic religious order reveals that the Islamic authority and legitimacy given to political institutions is shaped by political interests, not by a religious doctrine. In their research entitled ‘The Effect of Religious Restrictions on Forced Migration’, Kolbe and Henne (2014) evaluate thirteen countries, including Afghanistan, which are responsible for the most forced migrations. They believe that Afghanistan has suffered the most from religious violence. In their article entitled ‘Did Secularism Fail? The Rise of Religion in Turkish Politics’, Taydas et al. (2012) compared the Iranian and Afghan societies and stated that Afghanistan adopted a more moderate attitude toward a religious state in the post-1995 era. The rulers in this country were willing to incorporate religion into the public and social domains, but they did not believe in a state-based religion as a proper one. In the article ‘Religion, State, and Democracy: Analyzing Two Dimensions of Church-State Arrangements’, Michael Driessen (2010) believes that in Islamic countries, especially in Afghanistan, the empowerment of religious authority can pave the way for dangerous Taliban policies and expose the society to a sacred form of violence.

What distinguishes this study from the existing works is that it a) matches the Sharia-based order of the Taliban, in both governments, with the theoretical pattern of the sacred society proposed by Davis, b) analyzes the changes in modern Afghanistan, c) analyzes the differences in Afghanistan over time, and d) expresses the reason for the change in the political and social behavior of the Taliban.

4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

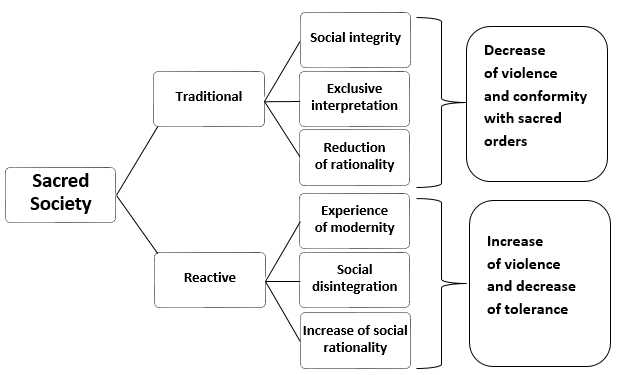

Religiously speaking, societies can be divided into three types with respect to the way they organize their social order. They include sacred, secular, and pluralist societies. Among them, a sacred society, which can be either traditional or reactive, is greatly uniformed. According to Charles Davis, such societies, as opposed to secular ones, consider social order as a superhuman entity which is devoid of the rationalistic dimensions of man (Mohaddesi 2019: 50–53). In their view, the social order has a transcendental origin, i.e., they see social order and its rules as God-given, far from being a human construct, remaining intact and flawless over time (Mohadessi 2007: 78). The legitimacy of the rulers in such societies depends heavily on their animosity towards non-religious societies. The relationship between these two societies is not an easy one. They either coexist in a state of mutual ignorance or isolation, or recourse to war and violence to compel conversion or submission (Davis 1994: 122). Hence, a sacred society is a religious society that emphasizes religion and religious authority in its various layers. Even the political power is viewed from a religious and sacred perspective because it is considered to be ordained by God. Therefore, the absolute obedience to the authorities in such societies is not a civil obligation but a religious duty, which shows the degree of faith and sincerity of individuals (Firahi 2003: 21 and 25). Furthermore, in such societies, the socio-political order originates from the transcendental. Therefore, the absoluteness of the transcendental is transferred to something that is limited or finite. Challenging such a system has hazardous consequences, and the guardians of this system are beyond criticism. Normally, the violators of these rules are deemed as outsiders and satanic (Mohaddesi 2007: 90).

Davis continues to say that there are two types of sacred society. The first is a ‘traditional sacred society’ in which modernity and its features are not to be found; hence, it can continue to exist as long as it is intact from the effects of modernity. In such a society, the direct and pervasive influence of religion as a superhuman or sacred entity is evident. That is why it is monolithic and accepted in its entirety by the people, whose management does not require repression and extreme violence (Mojtabaiee 1973). The other type of sacred is a ‘reactive sacred society’ formed to oppose modernity (Davis 1994: 123). Through its particular understanding of religion, this society considers the social and political order to come from God. To be more precise, God is enslaved by certain religious institutes to consecrate a particular social and political order (Mohaddesi 2007: 93). To resist disintegrating and relativistic processes, such a society begins to monopolize the social rule. However, since it faces many obstacles in achieving its goals, it gradually leads to strictness and violence at different social levels. According to Davis, it is basically impossible to sustain a traditional sacred society in the modern age because unity is one of its primary characteristics. Globalization and the revolution in communication through the development of media and virtual networks have led to the dissolution of traditional borders and the independence of large and small societies. Consequently, the restoration of unity in a society in which people's presuppositions have been changed by modernity and they have come to rationalization is always accompanied by violence.

Fig. 1. Davis's conceptual model of a sacred society

According to the above model, in a sacred society and system, contrary to a secular society, the belief in the transcendental and sacred origin of political rule consecrates all the laws. It is precisely for this reason that any opposition to the rulers of such a society is forbidden (Firahi 2003: 25–27). This society is not receptive to pluralism, and the monolithic political order is based on violence and submission rather than on dialogue and compromise (Mohaddesi 2007: 78).

After the dimensions of Davis's theoretical pattern are specified, it is time to compare the Taliban's sacred society and Sharia-based order with these dimensions to detect whether or not they fit together.

5. DAVIS'S SACRED SOCIETY AND

SOCIAL ORDER

IN BOTH TALIBAN GOVERNMENTS

According to Davis's theory, which classifies sacred societies into traditional and reactive forms, this study analyzes the Taliban rule in both of its governments, the first from December 1, 1996 to 2001 and the second since August 2021.

5.1. Davis's Traditional Sacred Society and the Taliban Order

In the name of religion and their own interpretation of it, the Taliban started to set up and implement particular plans and programs the ultimate aim of which was to bring Afghanistan under Sharia law. In this vein, their attempt to reconstruct the Afghan society can be described as a Sharia-based order. The ideological foundations of the Taliban system stem from four primary factors, including a) Deobandi thought, b) Islamic Sharia modeled on the practices of the Rashidun Caliphs, c) Pashtunwali tribal beliefs, and d) Wahhabism (Badakhshan and Keshavarz Shokri 2023; Tajik and Sharifi 2009: 41–42; Rashid 2000: 219–305; Ahmadi 1998: 27; Shahraki 2021: 74). Now, it is time to see whether this order fits Davis's traditional sacred society. The fit will be assessed in terms of the four main features of Davis's theory, including social integrity, exclusive interpretation of Islam, reduction of rationality, and reduction of violence.

5.1.1. Social integrity

The Taliban came to power at a time when Afghanistan was still a traditional society with very few features of modernity. Given that a pre-modern society is integrated and that people's life-worlds tend rather to be the same (Burger et al. 2002: 73), the Taliban faced an ethnically diverse society but almost a unified one in terms of culture and intelligence during their first rule in the 1990s, when socialization process and socializing organizations were not very different. They encountered scattered and partisan ethnic identities, with Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks being the most influential groups. The Taliban recruited their followers primarily from the Pashtun tribes on both sides of the Durand Line in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the largest ethnic group and the founders of Afghanistan (Qureshi 1996: 99; Sungur 2016: 441). As a result, they emerged with a more cohesive and powerful tribal structure compared to other ethnic groups (Sajjadi 2001: 54; Najafi 2010: 43; Arzagani 2012: 60; Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 53). Ethnically, the population is about 55–60 per cent Pashtun, so they are ardent supporters of the Taliban, who come from the same ethnic group. Due to their well-known identity, based on a distinct tribal system and language, the Taliban have a significant influence on the other Afghan ethnic groups (Tajik and Sharifi 2008: 41–42; Vatanyar 2023: 438).

These ethnic disparities, especially the unequal distribution of power, have contributed significantly to socio-political problems such as ethnic conflicts, stalled state-nation building processes and exacerbated political crises. These factors are potential or actual obstacles to social integration (Norouzi, Lavasani, and Nazifi 2023: 270; Rotberg 2009; Maizland 2021: 4). However, despite these ethnic challenges, the Taliban faced a society marked by backwardness, tradition, prejudice, and resistance to modernity and renewal, with similar socialization processes and institutions. In such a society, national identity, patriotism, and a preference for national interests over ethnic considerations had not yet emerged among the general populace (Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 52; Edwards 2010: 967).

While ethnicity is a fundamental framework for both cohesion and division within Afghanistan's traditional society, the role of religion as a unifying factor among different ethnic groups should not be overlooked. Unlike ethnicity, religion seeks solidarity and identity beyond the narrow confines of family, tribe, sect or nationality, extending to the broader ‘Ummah’. The Taliban leveraged religious sentiments to foster unity among the masses and promise a return to security (Fazli 2022: 115–116). According to the statistics, 70–80 per cent of Afghans lived in the rural areas before 1964. There was a traditional, rational and intellectual system with less complexity than in modern times. Furthermore, Islam as the religion of 99 per cent of the people and Sunnism as the religious sect of about 80–89 per cent of the society were more conducive to unity (Kramer 2021: 3). Weak links between urban and rural areas, and between Afghan villages and the outside world, strengthened the Taliban's power. The relatively deep ties between rural inhabitants and religious forces, along with the influence of religious leaders as guides to worldly and spiritual salvation, provided the Taliban with an opportunity to attract the masses and foster unity among them (Maizland 2021: 4).

Based on these factors, what Davis calls ‘social integrity’ as one of the characteristics of a sacred society holds true about the first Taliban's government in Afghanistan as its primary characteristic.

5.1.2. The exclusive interpretation of Islam

In his definition of a traditional sacred society, Davis holds that this society, unlike a secular society, sees the social order of divine ordinance as being well away from human agency (Davis 1994: 122). This situation was also present in Afghanistan during the first period of the Taliban rule. According to the Taliban, there is only one way to bring order to society, and that is through adherence to their interpretation of Islamic Sharia. Their primary objective was the revival of the Caliphate within the political structure of Islam in the form of the ‘Islamic Emirate’ (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 45–44). They even referred to their state as an Islamic state. Gradually, in practice, religion became a tool at the service of the Taliban; in other words, religion turned into an ‘ideological tool of the state’. In fact, the state-based religion is the direct output of a religious state. From this perspective, the Taliban believe that the legitimacy of such a state will be undermined when the unfaithful forces take power (Mohaddesi 2007: 88; Glinski 2020: 3). Such an attitude toward Islam in this state defines people as merely passive and submissive agents. It is the state and religious leaders that have the right to interpret and impose divine orders, and people have no right to ever cooperate or participate in the power and decision-making processes. The Taliban considered their state as a divinely ordained to change the Afghan society. Hence, the relation between the sacred thing and the power structure allows the ruling individuals and groups to impose their own tastes, attitudes and hegemony on the society, creating a socially unified atmosphere (Maley 1998; Badakhshan and Keshavarz Shokri 2023: 304; Hossein Khani 2011: 215–216).

Thus, the society that the Taliban governed by during their first period of rule was exclusive and served the Taliban's interests, much like Davis's concept of a sacred traditional society. Their interpretation of Islam was among the most primitive, brutal, and anti-intellectual. They had an inflexible interpretation of Islam that was not forward-looking or aimed at societal development, but rather regressive and reliant on violence. Therefore, violence, rigidity, and extremism were the three prominent characteristics of the Taliban (Baker 2021: 8; Matinuddin 1999: 78; Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 202).

The Taliban sought to eradicate all signs of a modern state from the society they governed. Through the imposition of strict and exclusive laws and decrees, they also organized various political and social affairs based on their interpretation of Islam. The Taliban leader, Mullah Omar, who was introduced as the ‘Commander of the Faithful’, based his governance on Sharia, the traditions of the Prophet (PBUH), and the Rashidun Caliphs, and considered the primary mission of the Taliban to be the implementation and promotion of Islamic Sharia in society (Badakhshan and Keshavarz Shokri 2023: 304–305; Roy 2008: 62; Fazli 2022: 122). Although the group modeled its decision-making on the Pashtun tribal council (Jirga), with its growing power, all the decisions were made solely by Mullah Omar. As a result of his individual decisions and instant orders, the ugly face of the Taliban, which was supposed to establish an Islamic state, was exposed (Fazli 2022: 115; Badakhshan and Keshavarz Shokri 2023: 304–305; Hossein Khani 2011: 215–216). The statements by Mullah Ahmad Wakil, the Taliban's spokesman at that time, about Mullah Omar clearly reveal his authority and discretion:

Decisions are based on the beliefs of the Commander of the Faithful. We do not need consultation; we believe that our actions are based on the tradition (rules and actions of the Prophet Muhammad). We follow the beliefs of the Emir. Here, we do not have a president, but we have the Commander of the Faithful. Mullah Omar holds the highest position, and the government cannot make decisions without his approval. The principle of public elections is against Sharia, and that is why it is avoided (Roy 2008: 23).

This aligns with Davis's theoretical pattern of the monolithic nature of traditional sacred societies.

5.1.3. The reduction of rationality

In Davis's theoretical pattern, the third criterion for a traditional sacred society is the reduction of rationality. Basically, in premodern societies, the high level of social integrity and the unified meaning-making order across different segments form a common lifeworld in which emotion overcomes reason (Burger et al. 2002: 74). According to Davis, the individuals in traditional sacred societies are believed to be incompetent to solve problems related to human life and destiny; salvation does not depend on individual's will, but it is transcendental and supernatural. The return to a transcendental origin is necessary and right (Davis 1994: 125).

One of the consequences of the Taliban's rise to power in 1996 was extremism, superficiality, dogmatism, and the suspension of rationality in individual, social, and political matters. During the first period of the Taliban rule, they fought and opposed all norms of the international community, manifestations and symbols of modernity, development, and nation-building processes (Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 202–203 and 207–208; Shahraki 2021: 71 and 77–79). Instead of relying on the principle of equality and recognizing reasonable civil rights, this group operated on the basis of ethnic and tribal socialization. Despite the Taliban's claim to follow and be loyal to Islamic Sharia, in practice, they adhered more to the traditions and laws of the Pashtun tribe. They strived for the superiority of their tribal and ethnic group, claiming, for instance, that the tribe of the Muslim Caliph must be the superior tribe (Fazli 2022: 117–118; Vatanyar 2023: 438; Mojdeh 2003: 33).

Apart from the Taliban's irrational and illogical considerations on ethnic issues, their reliance on and adherence to religion was also entirely outside the realm of rationality and wisdom. Their fundamentalist views were incompatible with any form of modern rationality. They were and are fanatics with a very superficial and literal understanding of the religion. Their opposition to the teaching of experimental and natural sciences like chemistry and physics and replacing them with religious sciences to provide a basis for individuals' happiness and salvation, the preference of the madrasas over schools, the resort to violence and inflexibility, the pursuit of intense sectarian hostilities, especially against Afghan Shiites, the strong opposition to Western civilization, the regression to pre-modern times, the rigid interpretation of religious concepts, self-righteousness, and the excommunication of other Islamic sects and denominations are only a small part of their violence, ignorance, and alienation from rationality (Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 193; Ahmadi 1998: 27; Shahraki 2021: 193; Sardarnia and Hosseini, 2014: 59; Emami 1999: 90; Bakhshayeshi Ardestani and Mirlotfi 2011: 34; Rashid 2000: 75; Amini and Arifani 2021: 66).

The worst part of this scenario is the Taliban's attitude and behavior towards Afghan women. They believe that women symbolize the honor and dignity of men and, therefore, must be protected (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 48; Morshedizad 2001: 44). With this mindset, during the first period of the Taliban rule, women were deprived of all individual and social rights and freedoms. Girls were confined to their homes and banned from education. Women were not allowed to leave the house, travel without a male guardian, work in public or private institutions, drive a car, buy and sell goods, walk around the city, or participate in political, social, and economic activities. They were only allowed to attend funerals, visit the sick, and make urgent purchases. They also had to wear a burqa (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 42–48 and 56; Rasouli 2016: 339–360; Kashani, 1998: 58; Abbaszadeh Marzbali and Taleshi Kelti 2022; Maghsoudi and Ghalladhar 2011: 180; Harrison 2022). Notably, of the 33 decrees issued by the Taliban's Department of Promotion of Virtue in 1996, 14 were specific to women, and 17 were common to both men and women (Tajik and Sharifi 2009: 42).

The restrictions and deprivations imposed on women are highlighted in the book Al-Emarah al-Islamiyah wa Nizamha, considered as the constitution and manifesto of the Taliban movement, written by Abdul Hakim Haqqani. It explicitly states that politics and governance are exclusively for men and that women have no right to enter these domains under any circumstances (Abdul Hakim Haqqani, 1443 AH/2022 AD [N.d.]). Men were not spared from certain restrictions either. For example, they were required to wear turbans, keep their hair short, grow beards, wear shalwar kameez, pray in congregation and avoid individual prayer. According to the Taliban's sacred orders, their state strongly opposed radio, television, music, painting, sculpture and other arts for all men and women. The historic Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed as Afghanistan's cultural heritage. They only acknowledged cricket as a legitimate sport in the country (Clements 2003: 2019; Bankiyan Tabrizi and Naderi Chalav 2023: 31; Marsden 2000: 60, 62, and 75).

The Taliban deemed their irrational actions, such as mutilations, lashings, deprivation women of many human rights and freedoms, particularly education, torture of opponents, destruction of ancient artifacts and statues, to be in compliance with Muhammadan Sharia (Pollowitz 2014: 6). However, according to many rational thinkers worldwide, these actions are completely incompatible with reason.

5.1.4. The reduction of violence

As mentioned above, according to Davis, in an integrative and culturally uniformed traditional sacred society, every individual accepts the social order there, and public relations stem from a transcendental will. Hence, there is no space for questioning; everyone should conform to the religious laws as interpreted by the religious elites and not be deceived by modern rationality. According to Davis, a result of the dominance of this form of traditional sacred society is the reduction of violence.

The experimental studies of the first Taliban government suggest that this theoretical element by Davis, i.e. the reduction of violence, has nothing to do with that rule of theirs; rather, it was quite different in the case of Afghanistan. The fact is that the Taliban's violence was more noticeable at that time compared to the present (Maley 2001: 14). A distinguishing characteristic of the Taliban during this period is ‘violence’ and ‘inflexibility’ (Sarafraz 2011: 111–115; Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 45; Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 202). The assassination, torture, and murder of opponents by the Islamic Emirate were so excessive that the only countries which formally recognized it were Pakistan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia (Shaffer 2006: 283; Badakhshan and Keshavarz Shokri 2023: 303). Thus, the Taliban gradually increased the discontent of people, especially the non-Pash-tun ethnic groups. This was due to their reductionist religious attitudes, inflexible mindset, violent methods to achieve their goals, which they saw as complying with those of the Prophet, glorification of war as a symbol of power, and rejection of peaceful methods such as persuasion, dialogue, and negotiation (Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 202). The Taliban turned blind eyes to consecutive UN resolutions and expelled many foreigners from Afghanistan. Homosexuals and adulterers were stoned to death, and the hands of thieves were amputated. People were dragged out of their shops for mass prayers in the mosques. They treated people according to tribal laws. They would not negotiate with the Akhavans, Jamaatis and Maududis (Clements 2003: 219).

According to reports by the international human rights organizations, the Taliban killed thousands of Afghans during their first government in 1996. One example is the massacre of thousands of Hazaras in Mazar-i-Sharif in a few days in August 1998, which was considered genocide. According to Human Rights Watch reports, after Mazar-e Sharif fell into the hands of the Taliban, their leader declared that Shia Hazaras were infidels and worthy of killing and looting. The mass killing of those people in such provinces as Sar-e Pol and Bamiyan from 1999 to 2001 is an example of religious violence (Giustozzi 2009: 249).

5.2. Davis's Reactive Sacred Society and the Taliban's Rule

With the fall of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in 2021, the second period of the Taliban's Islamic Emirate began. During the Republic era, efforts were made to democratize and modernize Afghanistan with the support of Western governments, particularly the United States. These efforts included rebuilding and reinforcing the police and the army, holding presidential and parliamentary elections, reviving the modern administrative and tax systems, enhancing infrastructures and the institutional foundations of the government and civil society, reducing poverty, taking serious steps against terrorists, and boosting economic and social conditions. Efforts were also aimed at creating governmental institutions, gaining international recognition (Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 48), promoting human rights, especially women's rights, facilitating their participation in political, social, and cultural spheres, ensuring various freedoms and enabling their employment in government and private sectors (Hosseini 2023: 289–388; Kazem 2005: 507–517; Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 49–51). Many women were appointed as judges, and some even entered the parliament (Snow and Benford 2000: 85). However, these efforts did not achieve significant and tangible results. Several reasons can be cited for this failure, the most important of which include:

· These measures were limited to specific sectors and groups within Afghan society, resulting in the persistence of unfavorable conditions during the Republic, especially for women. These included a lack of legal protection, imprisonment of girls and women for fleeing their homes (Human Rights Watch 2012: 288–293), and divisions within the military and security forces. All this led to dissatisfaction (Moghaddas 2021: 60–61), widespread corruption, arbitrary and ethnic-based appointments and dismissals, embezzlement of public funds, lawlessness, and nepotism (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 54).

· The lack of a consistent war strategy against the Taliban, the centralization and monopolization of power in the presidential palace (Schroden 2021: 21), the inability of the central government to establish order, security and justice, ethnic and tribal diversity overshadowing national unity, ethnic conflicts and the lack of a cohesive national identity (Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 196; Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 50–53), internal governmental disputes leading to a crisis of authority, and a lack of consensus on national interests (Marzbani and Amiri 2023: 162; Gazerani, Athari Allaf, and Arian Manesh 2022: 130–135).

·

These

numerous challenges and obstacles reflect the fragility of the state and the

significant decline in its power during the Republic era. In reality, the

Karzai and Ghani administrations could not effectively

address the challenges posed by traditional forces (Moghim 2023: 541–542),

because neither had national roots, but sprang from

a confederation of tribes. As a result, behind all the formal developments, the

principle of ethnic and tribal identity, solidarity and corresponding loyalties

prevailed (Salehi Amiri 2010: 82–83; Sardarnia and

Hosseini 2014: 53).

· Considering the above points, it can be seen that the society over which the Taliban rule during their second period in power is not fundamentally different from the society of their first rule or even the republican era. Thus, it cannot be definitively said that the contemporary Afghan society has moved beyond the traditional sacred society envisaged by Charles Davis. Once again, different ethnic groups, primarily lacking a participatory political culture, are striving to assert their tribal dominance, thereby creating a fertile ground for ethnic conflicts (Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 53). In other words, ethnic differences, along with the gap between modern and sacred orders have led to disruption and chaos (Joscelyn 2021: 15).

· Hence, this study also seeks to identify whether the Taliban's Sharia-based rule in modern Afghanistan is consistent with the elements of Davis's traditional reactive society, including, social disintegration, Afghans' experience of modernity, the growth of social rationality, and the increase in violence.

5.2.1. The disruption of social integration

According to Davis, when a traditional sacred society is exposed to modernity and its elements, integrity and unity among its members give way to disintegration and separation, and the absolutist view of the origin of social order gives way to cultural relativism. Thus, despite planned efforts to sustain integrity and monopolized social order, cultural disruption, relativism and pluralism are bound to occur (Davis 1994: 123). Historical and experimental evidence shows that Davis's re-cent claim is testified with respect to the Afghan society, in its entirety, under the second Taliban rule.

With the Taliban's return to political power, social and political integration has been disrupted. Conflicts and clashes of interests exist between different ethnic groups and social forces, as well as between government officials and agents themselves. The Pashtun ethnic group has a more cohesive tribal structure than other ethnic groups, and is more powerful due to its dominance in leadership and key government positions, seeking to impose its dominance over other tribes and ethnicities (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 53–54; Maizland 2021: 4). This situation plays a significant role in creating fragmentation, division, and tension in the society, threatening the national unity. The Taliban's ethnic and sectarian revenge exacerbates this (Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 51–52; Rotberg 2009: 58).

The above problem is not limited to the social system and its forces; it also extends to government officials and agents. During the first period of the Taliban rule, there was more integration and unity among them than during the second period. In the early years of the movement, Mullah Omar managed to present himself as a charismatic and enigmatic savior, but his leadership style later led to opposition against him (Bahrami 2023; Bankiyan Tabrizi and Naderi Chalav 2023: 35; Qandil 2022). In the second period, internal differences among the Taliban have become apparent. For instance, in February 2022, some of the most prominent Taliban leaders criticized the country's direction. For example, Sirajuddin Haqqani, the interior minister and leader of the Haqqani network, stated that the Taliban's monopoly on power was tarnishing their entire system. Mohammad Yaqoob, the defense minister and son of Mullah Omar, advised the Taliban to meet the people's demands. Abbas Stanikzai repeatedly voiced his opposition to the ban on girls' education. Meanwhile, Hibatullah Akhundzada issued decrees banning Taliban officials from polygamy, yet they continued to practice it, disregarding his orders. Furthermore, Taliban forces ignored Akhundzada's general amnesty order and continued extrajudicial killings (Qandil 2022). Akhundzada tried to suppress his opponents by appointing trusted allies and supporters from Kandahar to government positions and even moving his decision-making center from Kandahar to Kabul (Mahmoudi 2020: 218).

Consequently, figures like Haqqani, Mohammad Yaqoob Mujahid, and Abdul Ghani Baradar, the deputy prime minister for economic affairs, are more pragmatic compared to other leaders like Akhundzada and advocate for balanced international relations. Some Taliban members, including Mujahid and Baradar, despite being part of the Kandahari Taliban, oppose Akhundzada's policies. Haqqani is mainly based in southeastern and eastern Afghanistan, but Akhundzada governs Afghanistan with the support of a small circle of religious leaders and his supporters in Kandahar. Haqqani places key relatives in government positions (Bahrami 2023; Qandil 2022). Baradar led the peace negotiations with the United States and holds weaker positions than the other Taliban branches. Military leadership belongs to Mohammad Yaqoob, and the Haqqani network is under Haqqani's control (Bahrami 2023). After Mullah Omar's death in 2013, the Taliban fragmented into different factions. The political branch led by Baradar pursued negotiations, while the military branch, led by Akhundzada, aimed to revive the Islamic Emirate through military operations (Mahmoudi 2020: 218).

Certainly, the challenges facing the Taliban are not limited to internal conflicts. Currently, they face several opponents, both outside and inside Afghanistan. The external opponents are based in countries such as Turkey, Tajikistan, and European nations. Internally, there are non-Afghan extremist groups like Tahrik-e Taliban in Pakistan, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Ansarullah in Tajikistan, the East Turkistan Islamic Movement, and particularly ISIS of Khorasan.* The Taliban lack the serious resolve to combat these groups. They have been fighting alongside these groups for years, sharing familial and kinship ties. They fear that a serious confrontation with these groups could have a negative impact on their own troops. Consequently, they lack the necessary capacity to control the terrorist groups present on the Afghan soil (Bathaee, Shafiei Sarvestani, and Esmaeili 2023: 157; Bahrami 2023; Vatanyar 2023: 446; Hosseini 2018: 199). Although the Taliban pledged to sever ties with al-Qaeda* as part of the Doha Agreement with the United States, in practice, they have not strictly adhered to this commitment. The assassination of Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader and mastermind of al-Qaeda by American drones near the Taliban palace indicates that the Taliban have violated this agreement (Vatanyar 2023: 447).

Therefore, one of the factors threatening the Taliban's governance is their internal conflicts and power struggles. They currently face a crisis of order and security (Sardarnia and Hosseini 2014: 54). This situation has led to the reinforcement of Salafi-Jihadi groups in Afghanistan and has provided an opportunity for terrorist groups to operate freely in the country (Lafraie 2009: 104–105).

However, Davis's perspective that ‘the confrontation of a sacred traditional society with modernity and its manifestations leads to cultural relativism replacing the absolutism of the general source of social order’ does not apply to the Taliban-ruled society in its second term. Despite two decades of the republic governance and efforts to build a new state-nation relationship, the attempts have essentially failed. As a result, the society under the current Taliban rule does not differ significantly from the traditional society under the first Taliban regime. Neither have the perspectives and positions of the Afghan people on various social, political, cultural and economic issues changed to embrace modernity and democracy, nor have the nature and methods of Taliban governance evolved to accept political development and transformation. On the one hand, people are grappling with ignorance, poverty and inequality. On the other hand, political leaders are entangled in power struggles, ethnic biases, and extremist ideologies. Therefore, the diversity and plurality in such a society is primarily ethnic and tribal rather than cultural (Edwards 2010: 967; Rotberg 2009: 58; Roy 1993: 73; Mojdeh 2003: 33). Cultural relativism, the emergence of skepticism towards traditional values and the adoption of a participatory political culture occur in a society wh ere people have achieved sufficient intellectual and political maturity and wh ere government officials see themselves as the people's servants, not their guardians.

5.2.2. The experience of modernity by Afghans

According to Davis, when modernity succeeds in making inroads into a traditional sacred society, influencing people's thoughts and actions, and making them doubt their anti-modern reactions, there will be a change in the society. Hence, as modernity spreads, with the ease of communication and universal technology, one can expect a new social order whose prominent characteristics are social disruptions and differences (Davis 1994: 123). This situation does not apply to the society under the Taliban in their second era. Despite some fundamental changes that occurred during the republic period, the current Afghan society remains traditional, closed, and undemocratic. Taliban officials still oppose modern values, new civilities, democracy and its requirements; instead, they advocate regression, Salafism, fundamentalism, and a rigid dogmatic interpretation of religion marked by violence and strictness, piety and a sacred view of historical achievements (Yousaf-zai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 201; Fazli 2022: 111–112). The socialization of the Taliban is oriented towards local channels, on one hand, and religious channels, on the other. Thus, their perspective on matters is both subnational, or ethnic, and transnational because it is based on traditional moral and religious values that are not accepted by the international community. In the Taliban's traditional governance, international norms and values are considered illegitimate and, therefore, not taught to their followers. This Taliban approach implies an anti-social or anti-international community stance for the Afghan nation. The Taliban view their domestic policies as independent and different from the international community. Similarly, they attempt to internalize local-religious norms and values, keeping the Afghan nation away from the influences of modern identity and civility. Additionally, state-building is pursued through coercion, force, and policies of exclusion and suppression (Yousafzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 203–201; Marsden 2000: 110–109). Furthermore, as in their first period of rule, the Taliban disregard human rights, especially the rights and freedoms of women and ethnic minorities, and continue the same violent, harsh, and prejudiced treatment as before, and there is no sign of democracy in their governance (Tohidi and Qasemishahi 2022: 699).

All the aforementioned considerations not only highlight the ‘abnormal’ internal and external behavior of the Taliban but also suggest that they will remain unrecognized by the rest of the world if they avoid accepting international norms and values or engaging in international socialization (Yousafzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023: 193 and 207–208). These abnormalities have led some to describe the current state of the Taliban as neither a full-fledged government nor a complete mo-vement, but rather a liminal state between a government and a movement (Ibid.: 194). During their first period of rule, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates recognized the Taliban, but, in the current period, no country or global organization has recognized their government. Only dialogues with their representatives have taken place, or their representatives have participated in some global conferences (Ansari 2002: 153; Savari et al. 2022: 96; Azizi 2021: 7). Countries like China, Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Turkmenistan have handed over the Afghan embassy to the Taliban representatives without officially recognizing their government (Tohidi and Qasemishahi 2022: 695–696).

It should be noted that although the overall nature and governance style of the Taliban in the new period has not changed significantly compared to the first period, some minor and secondary changes can be observed. For example, the Taliban have realized that if they continue to pursue their goals and ideals as violently and overtly as before, the pressure and obstacles on the part of the international community will persist, posing a serious threat to the maintenance of their government. Therefore, they may gradually seek to change their behaviors and policies, even if only superficially. They may reduce violence (Mahmoudi 2020: 214). In any case, given that more than 20 years have passed since their first rule, and that unintended changes have occurred both in the Afghan society and globally during this relatively long period, they are trying to manage the society with more caution and fear. At present, parts of the Afghan population, especially women, are dissatisfied and protest against the Taliban's policies. The most dissatisfied individuals are likely to be those affected by the reforms that took place during the republican period. Despite the failure of the state-building and democratization process in Afghanistan during the republican era, some positive effects of those reforms, albeit minor, have permeated contemporary society and parts of the Afghan population. Therefore, it cannot be completely denied that the reforms during the republic did not have a positive impact on the current Afghan society in areas such as political institutions, political participation, political parties, minority rights, various freedoms, women's rights, and education (Sajjadi 2009: 164; Sharifi and Adamou 2018: 3).

5.2.3. Increase of social rationality

According to Davis, in a reactive sacred society, social order and the meaningfulness of social life do not depend on rational discussion which leads to a negotiation among discrepant opinions. Therefore, it is possible to express different opinions and achieve fairly rational results (Davis 1994). This feature of Davis's theory partially matches Afghanistan under the second Taliban rule. In contemporary Afghan society, there are signs of change in thoughts and attitudes among some sections of the population exposed to the manifestations of modernity, including mass media and virtual networks. These individuals have come to understand that they should question the Taliban leaders' claim that their aim to establish the Islamic Emirate is nothing more than the implementation of Sharia law. They should also consider the possibility that the Taliban have turned religion into a tool for governance. Considering that the Taliban viewed the Islamic republic government under Karzai and Ashraf Ghani as a secular government which promoted corruption and immorality and served the United States (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 54–53; Maizland 2021: 4), people ask themselves whether the Taliban are now subject to criticism for their governance? Achieving such an understanding, which means recognizing the true nature of the Taliban's religious government, can be seen as a sign of growing social rationality (Sajjadi 2009: 11–10). Therefore, from the perspective of these segments, although the Taliban claim to be committed to implementing Sharia rules and acting in accordance with religious interests, they may have to overlook some religious norms when necessary, for example, in the pursuit of power (The Visual Journalism Team 2021: 2).

However, beyond this group, the majority of the society still lacks intellectual and cultural maturity and is unable to act beyond the confines of local and ethnic considerations. The thinking of the majority of the Afghan population is influenced by a traditional and archaic society interwoven with various customs and tribal traditions, making it difficult to identify a single framework for defining the identity of the Afghan people. Such a population lacks the instrumental rationality to prioritize national interests over ethnic considerations and national patriotism (Fazli 2022: 115; Marsden 2000: 93; Roy 1993: 73).

This situation also applies to the Taliban leaders and their governmental officials. Although a combination of internal and external factors necessitates that the Taliban reflect more critically on their self-serving and so-called official interpretations of religion and recognize that such an approach to religion has rendered religious values and norms invalid and made them unacceptable to part of the current Afghan generation (Hassan 2021: 25), they continue to resist and persist in pursuing their irrational goals and ideals. They are also ensnared by ethnic considerations and insist on the superiority of the Pashtun ethnicity over others, thus attempting to impose their tribal inclinations, intertwined with religious considerations, on the people of Afghanistan (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 55; Fazli 2022: 116; Mojdeh 2003: 33).

5.2.4. The increase of violence

To delineate his theoretical pattern, Davis says that, after the permeation of modernity into the reactive sacred society, disintegration occurs, and cultural relativism appears in consequence. This change makes political leaders try to artificially restore integrity and monopolize social order. Since they fail to do so and people do not care about the rulers' attempts, it makes violence and pressure the only choice for the state. In this way, the minimum amount of tolerance that exists in the traditional sacred society disappears in the reactive sacred society (Davis 1994: 122).

In modern Afghanistan, which is considered as a reactive sacred society according to Davis's pattern, historical and experimental evidence shows that the situation somewhat validates Davis's view, because the violence employed by the second Taliban government is no less than that in their first government. Thus, tyranny and obscurantism have been revived by the Taliban once again. Despite international opposition, the Taliban continue on a path that is incompatible with the accepted international norms. Violence and rigidity remain as the prominent features of Taliban governance, stemming from the traditional Pashtun culture (Shahraki 2021: 74; Bakhshayeshi and Mirlotfi 2011: 34; Vatanyar 2023: 439). While they claim that their government is established based on Islamic Sharia law, modelled on the Rashidun Caliphs, and outwardly emphasize principles such as equality, brotherhood, opposition to all forms of tribal and linguistic prejudices, and the protection of the lives, property, security and peace of Afghan Muslims, the Taliban’s policies and practices have contradicted these tenets. Consequently, this relative tolerance has been violated, and violence has replaced it (Fazli 2022: 125–126). Enumerating the acts of violence committed by the Taliban would be a long list beyond the scope of this paper. Just a few examples of the Taliban's violent and irrational behaviors in their new rule include banning the publication of materials in any language other than Pashto on their official radio and newspaper ‘Sharia’, harassing, restricting and even killing of ethnic minorities, especially Shias in Mazar-e Sharif and the other Hazara areas (Fazli 2022: 125), strong opposition to modern societal development, modern civility and other manifestations of modernity (Amini and Arifani 2021: 306; Shahraki 2021: 75; Yousefzai, Sinaei, and Rafat 2023; Norouzi, Lavasani, and Nazifi 2023: 270), forcing men to grow beards, wear turbans, cut their hair short and wear traditional attire (Bankiyan Tabrizi and Naderi Chalav 2023: 31), requiring women to wear hijab and burqas, banning them from education, leaving the house, traveling and taking government or non-government jobs, and advising them to completely obey their husbands (Vatanyar 2023: 441; Habibi 2021: 127; Hosseini 2023: 389; Bathaee, Shafiei Sarvestani, and Esmaeili 2023: 160 and 173), and violent and inhumane treatment of women and misogyny (Bakhshi and Nourmohammadi 2023: 42 and 57–55; Taheri 2022: 95; Saeedi 2021; Hosseini 2023: 388–384; Mohammadi 1998: 68). The emergence of some discontent in the Afghan society and the flight of some elites from the country have compelled the Taliban be more cautious and reflective in their violent and strict actions, especially because the Taliban leaders know that confronting universities, closing or postponing education, and dealing with faculty members and students have very negative impacts not only on domestic opinion, but also on the views of other nations, governments, and international organizations towards them (Ali and Lan-day 2021: 36). This can increase the pressure on their newly-established government by human rights activists, women's rights defenders, political figures, journalists and social network users and, as a result, disrupt the order of the reactive sacred society (Semple 2015).

So the Taliban have somehow come to the realization that Afghans expect them to show a more lenient behavior and to reconsider their attitudes towards different layers of the society, especially their opponents and women. If they put violence aside and, instead, choose proper words and deeds, they can gain legitimacy and a stronger stance in competitive processes such as elections. There is no need for violence, war and terror to rule. Although the Taliban lack such a capacity (Nada 2021), there is evidence that they have shown more patience from the beginning of their new term in power and have tried to project a new image of themselves as changeable beings. The result of the discussions above is more or less consistent with Davis's theory of violence in a reactive sacred society.

6. CONCLUSION

This study sought to answer the question ‘whether or not the Taliban's intended rule in both of their governments matches Davis's theory of the sacred society’. What Davis calls a sacred society is a society in which social order is of a divine nature. Since it is not man-made, it is unquestionable. According to Davis, such a society comes in two forms. The first is a traditional sacred society which is integrative, monolithic, rigid, and anti-rational. The output of such a society is the reduction of violence and the observance of laws. The second is a reactive sacred society, which is a disintegrated society marked with relativism and cultural diversity, as well as increased rationality due to the permeation and influence of modernity. Since the state tries to restore integrity and monopolize the social order, it ends up with increased violence and absence of any form of easy-going behavior.

The results show that the Sharia-based rule intended by the Taliban in their previous and current governments in Afghanistan (the first from 1996 to 2001 and the second from 2021 onwards) matches Davis's theory in general, but not in detail. The society ruled by the Taliban in the first period corresponded to Davis's traditional sacred society, because its divine ordinance corresponded to the characteristics of a traditional sacred society mentioned by Davis, such as social integrity, stricture, counter-rationalism, and monopoly, especially in the case of religious interpretations. The only exception is violence. Davis believes that violence is reduced in a traditional sacred society because of its unified nature. However, historical and experimental evidence shows that violence increased in the traditional sacred society of Afghanistan during the first Taliban rule, as the Taliban employed increasing terror and threat to achieve their goals.

The Afghan society in the second period of Taliban rule resembles a ‘reactive sacred society’ as Davis describes it, and at the same time has some differences. The similarity lies in the Taliban leaders' goal of opposing modern civilization, the manifestations of modernity, and internationally accepted norms, which were the legacy of two decades of republican governance, manifested in such elements as democracy, rationalism, equality, freedom, elections, parliament, respect for human rights and women's rights. According to Davis, the Afghan society under the Taliban rule can be deemed as a reactive sacred society, in which the rulers are afraid of the penetration and expansion of modernity. Hence, they try their best to prevent it. Also, as Davis notes, the reactive sacred society ruled by the Taliban has traces of social fragmentation and division. Contrary to what Davis says, this fragmentation is not due to relativism, cultural diversity, or application of instrumental rationality, but rather it originates from ethnic, linguistic and tribal prejudices.

On the other hand, what distinguishes this society from Davis's reactive sacred society is that such a society, according to Davis, resorts to increasing and extensive violence because of its contact with modernity and the government's attempt to re-establish divine social order and restore unity. Despite resorting to violence during their second term in power and in comparison to their first term, the Taliban have acted more cautiously and meticulously overall. Therefore, if the level of their violence has not decreased in this period compared to the previous one, it has not increased either. While the Taliban aim to restore the absolute divine and sacred origin of the social order and maintain the unity and exclusivity in today's Afghan society, which may be transformed by the encroachment of modernity, they have realized that they will not be recognized by states and global organizations as long as they continue to use the current violent and irrational methods to pursue their goals and insist on continuing their abnormal behavior, which is in no way acceptable to the international community. This will make the serious challenges they face now more severe and complex. The Taliban's behavior indicates that they are unpredictable, so we will have to wait and see what happens in practice in the future.

The above considerations and views on the first Taliban government lead to the truth that Davis's theoretical framework does not completely match the reality of the so-called sacred societies. In a sense, his theory and the reality of the societies that he studies are different. In his book entitled Religion and the Making of Society: Essays in Social Theology, Davis mentions the post-revolutionary Iran as the best example of a sacred society, though, here again, there is not a complete match between theory and practice. Therefore, it can be concluded that what Davis identifies as the characteristics of a reactive and traditional sacred society only partially matches the societies known by the same name in history, and not more than that.

NOTE

* The organization is banned on the territory of the Russian Federation.

REFERENCES

Abbaszadeh Marzbali, M. and Taleshi Kelti, K. 2022. Taliban and Retrieving the Sovereignty: Strong Movement. Weak Nation-State. The Fundamental and Applied Studies of the Islamic World 4 (3): 105–130. doi: 10.22034/ FASIW.2022.350464.1179.

عباس زاده مرزبانی، محسن و کوثر طالشی کلتی. 1401. طالبان و بازیابی حاکمیت: جنبش قوی، دولت – ملت ضعیف. مطالعات بنیادین و کاربردی جهان اسلام. سال چهارم، شماره 13، صص 130-105.

Ahmadi, H. 1998. Taliban, Roots, Causes of Emergence and Growth Factors. Political-Economic Information 13 (132): 24–39.

احمدی، حمید 1377. «طالبان، ریشه ها و عوامل رشد». اطلاعات سیاسی-اقتصادی، سال 13، شماره 132، صص 39-24.

Ali, I., and Landay, J. 2021. U.S. to reduce Kabul Embassy to Core Staff, Add 3,000 Troops to Help. Reuters, August 13. URL: https://www.chan-nelnewsasia.com/world/us-reduce-kabul-embassy-core-staff-add-3000-tro-opshelp-21094....

Amini, M., and Arifani, D. 2021. The Taliban & Afghanistan: Conflict & Peace in International Law Perspective. International Journal of Law Reconstruction 5 (2): 306–316. https://doi.org/10.26532/ijlr.v5i2.17704.

Ansari, F. 2002 .Political-Social Developments of Afghanistan. Tehran: Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

انصاری، فاروق. 1381. تحولات سیاسی – اجتماعی افغانستان. تهران: وزارت امور خارجه.

Arzagani, M. 2012. The Rainbow of Afghan Nations. Kabul: Sobhe Omid.

ارزگانی، مسیح. 1391. رنگین کمان اقوام افغانستان، کابل: صبح امید.

Gazerani, S., Athari Allaf, H. and Arian Manesh, M. 2022. The US Presence and Exit from Afghanistan: Theory of Justly War. American Strategic Studies 2 (5): 125–145. doi: 10.27834743/ASS.2212.1065.

گارزانی، سعید. حنیف اطهری علاف. محمد آرمین منش. 1401. «حضور و خروج آمریکا از افغانستان؛ رویکرد نظریه جنگ اخلاقی»، مطالعات راهبردی آمریکا، سال 2، شماره 5، بهار، ص140-125

Azizi, S. 2021. The Recognition of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (Taliban) from the Perspective of International Law. International Studies Journal (ISJ) 18 (2): 7–22. doi: 10.22034/isj.2021.301775.1571.

عزیزی، ستار. 1400. شناسایی امارت اسلامی افغانستان (طالبان) از منظر حقوق بین الملل. مطالعات بین المللی. سال 18. شماره 70. صص 22-7.

Badakhshan, M., and Keshavarz Shokri, A. 2023. Political History of Afghanistan with an Emphasis on the Taliban Group. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, 27 Ordibehesht 2023. Alireza Pourrostam (collector) (pp. 291–314). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

بدخشان، مجتبی و کشاورز شکری، عباس. 1402. تاریخ سیاسی افغانستان با تأکید بر گروه طالبان. در: نخستین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، 27 اردیبهشت 1402. علی رضا پوررستم (گردآورنده). صص 288-265. مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد.

Bahrami, M. R. 2023. Taliban is the Main Shareholder of Power in Afghanistan. The speech of the former ambassador of Iran in Kabul in the third panel, the first national conference of Afghanistan and future prospects, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, 27 May 2023.

بهرامی، محمدرضا.1402. «طالبان عمده ترین سهامدار قدرت در افغانستان»، سخنرانی سفیر پیشین ایران در کابل در پنل سوم، اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اردیبهشت.

Baker, S. 2021. The Taliban have Declared the ‘Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,’ the Same Name It Used when it Brutally Ruled the Country in the 1990s. Business Insider, August 19. URL: https://www.businessinsider.com/taliban-declares-islamic-emirate-of-afghanistan-2021-8.

Bakhshayeshi Ardestani, A., and Mirlotfi, P. 2011. The Role of Political Soci-alization in the Formation of Talibanism in Afghanistan. Political Science and International Relations 4 (44): 29–56.

بخشایشی اردستانی، احمد؛ میرلطفی، پرویزرضا 1390. نقش جامعه پذیری سیاسی در شکل گیری طالبانیزم در افغانستان. علوم سیاسی و روابط بین الملل، دوره 4، شماره 44، صص 56-29.

Bakhshi, A., and Nourmohammadi, R. 2023. A Comparative Study of Women's Participation in the Taliban Government and the Republic in Afghanistan after September 11. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 61–41). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

بخشی، احمد. نور محمدی، ریحانه. ۱۴0۲. «بررسی تطبیقی مشارکت زنان در دولت طالبان و جمهوری در افغانستان پسا یازده سپتامبر»، در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد،27 اریبهشت. صص 61-41.

Bankiyan Tabrizi, A. M., and Naderi Chalav, M. 2023. A Comparative Study of the Approach of the Islamic Republic of Iran towards the Taliban's Rise to Power in 1996 and 2012. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 26–39). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

بانکیان تبریزی امیر محمد. نادری چلاو، محمد. 1402. بررسی مقایسه ای رویکرد جمهوری اسلامی ایران نسبت به قدرت گیری طالبان در سا ل های ۱۹۹۶ و 2021. در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اریبهشت. صص 39-26.

Bathaee, S. Y., Shafiei Sarvestani, E., and Esmaeili, B. 2023. Challenges Facing Afghanistan under the Leadership of the Taliban and its Future Scenarios 15 (3): 156–181.

بطحایی، سیدیحیی. شفیعی سروستانی، اسماعیل، و اسماعیلی، بشیر. 1402. چالش های پیش روی افغانستان تحت زعامت طالبان و سناریوهای آینده آن. روابط خارجی. سال 15. شماره 59. صص 182-157.

Burger, P., Burger, B., and Kellner, H. T. 2002. The Homeless Mind, Modernization and Awareness. Translated by Mohammad Savoji. Tehran: Nei.

Chalabi, M. 2007. A Textbook on Qualitative Research (Adaptive Historical) for PhD Students. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University.

چلبی، مسعود.1386. جزوه درس روش تحقیق کیفی (تطبیقی - تاریخی)، دوره دکترا، تهران: دانشگاه شهید بهشتی.

Clements, F. A. 2003. Conflict in Afghanistan: An Encyclopedia (Roots of Modern Conflict). ABC-CLIO. Bloomsbury Academic.

Davis, C. 1994. Religion and Making of Society: Essays in Social Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Driessen, M. D. P. 2010. Religion, State, and Democracy: Analyzing Two Dimensions of Church-State Arrangements. Politics and Religion 3 (1): 55–80.

Edwards, L. M. 2010. State-Building in Afghanistan. International Review of the Red Cross 92 (880): 991–967.

Emami, H. 1999 .Afghanistan and the Rise of the Taliban. Tehran: Shab.

امامی، حسام الدین. 1378. افغانستان و ظهور طالبان، تهران: شاب.

Fazli, R. 2022. A Comparative Study between the Islamic Emirate of Taliban in Afghanistan 1996–2001 and the Totalitarian State Model in the West. State Studies 8 (30): 93–132. doi: 10.22054/tssq.2022.70292.1335.

فضلی، رز. 1401. بررسی مقایسه ای میان امارت اسلامی طالبان در افغانستان و الگوی تمامیت خواه در غرب. دولت پژوهی، سال 8. شماره 30. صص 132-93.

Firahi, D. 2003. The Political Order and the State in Islam. Tehran: Samt.

فیرحی، داود.1382. نظام سیاسی و دولت در اسلام، تهران: سمت.

Giustozzi, A. 2009. Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia University Press.

Glinski, S. 2020. Feeling Abandoned by Kabul, Many Rural Afghans Flock to Join the Taliban. Foreign Policy, September 24. URL: https://foreignpo-licy.com/2020/09/24/taliban-kabul-rural-afghans-join-peace-deal/.

Habibi, Z. A. 2021. Crisis and Economic Challenges of the Taliban. International Security Monthly. Tehran: Abrar Maaseir.

حبیبی، ضامن علی. 1400. «بحران و چالش های اقتصادی طالبان»، ماهنامه امنیت بین الملل، تهران: ابرار معاصر.

Haqqani, A.-H. N.d. The Islamic Emirate and its System, presented by Hibatullah Akhundzadeh. Beirut: Dar Al-Ulum Sharia Library.

حقانی، عبدالحکیم) (1443 ه.ق- 2022 م)، الاماره الاسلامیه و نظام ها، قدم له هبه الله آخوندزاده، بیجا: مکتبه دارالعلوم الشرعیه.

Harrison, E. 2022. Taliban Order all Afghan Women to Cover Their Faces in Public. The Guardian.com. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/07/taliban-order-allafghan-women-to-wear-burqa.

Hassan, Sh. 2021. An Afghan Warlord who Steadfastly Resisted the Taliban Surrendered. Others may Follow his Lead. The New York Times, August 13. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/13/world/asia/afghanistan-mo-hammad-ismail-khan.html.

Hosseini, M. A. 2018. Pakistan's Foreign Policy towards Afghanistan. Negah Maasar Quarterly 2 (2): 188–201.

حسینی، محمدعلی. 1397. «سیاست خارجی پاکستان در قبال افغانستان. نگاه معاصر. سال2. شماره 2. صص 201-188.

Hosseini, S. M. A. 2008. The Sacred Utopia: A Criticism of the Four Patterns of Utopia Set by Western Thinkers Compared with the Islamic Utopia of Mahdi. 2nd ed. Tehran: Daftare Aghl.

حسینی، سیدمحمد عارف. 1387. نیک شهر قدسی: نقادی چهار الگو از جامعه آرمانی اندیشمندان غرب و مقایسه آن ها با جامعه آرمانی حضرت مهدی. چاپ دوم. تهران: دفتر عقل.

Hosseini, S. S. 2023. Investigation of Social Damage Caused by Violence against Women by the Taliban Regime. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects. Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 383-400). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

حسینی، صدیقه سادات. 1402. «بررسی آسیب های اجتماعی ناشی از خشونت علیه زنان توسط حاکمیت طالبان»، در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اریبهشت. صص 400-383.

Hossein Khani, E. 2011. Afghanistan's Security and the Issue of Gaining Power Regarding the Taliban. Political Sciences 15 (16): 205–240.

حسینخانی، الهام. 1390. امنیت افغانستان و مسئله قدرت یابی درباره طالبان. علوم سیاسی، شماره 16. صص 240-205.

Human Rights Watch. 2012. World Report 2012: Events of 2011. URL: https://archive.crin.org/en/library/publications/human-rights-watch-world-report-2012.htm.

Joscelyn, T. 2021. U.N. Report Cites New Intelligence on Haqqanis' Close Ties to al Qaeda. FDD's Long War Journal, June 7. URL: https://www.long-warjournal.org/archives/2021/06/u-n-report-cites-new-intelligence-on-haq-qanis-clos....

Kashani, S. 1998. Violation of Women's Rights in Afghanistan. Women's Rights Journal 1 (2): 59–98.

کاشانی، سارا. 1377. نقض حقوق زنان در افغانستان. نشریه حقوق زنان، شماره 2. صص 59-58.

Kazem, A. 2005. Afghan Women under the Pressure of Tradition and Modernity. California: Series of Publications on Afghanistan.

کاظم، عبدالله.2005. زنان افغان زیر فشار عنعنه و تجدد، کالیفرنیا/ میومند: سلسله نشرات درباره افغانستان.

Kolbe, M., and Henne, P. 2014. The Effect of Religious Restrictions on Forced Migration. Politics and Religion 7 (4): 665–683.

Kramer, A. E. 2021. Leaders in Afghanistan's Panjshir Valley Defy the Taliban and Demand an Inclusive Government. The New York Times, August 18. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2021/08/18/world/taliban-afghanistan-news#taliban-panjshir-valley.

Lafraie, N. 2009. Resurgence of the Taliban Insurgency in Afghanistan: How and why? International Politics 46 (1).

Maghsoudi, M., and Ghalladhar, S. 2011. Afghan Women's Participation in the New Power Structure after the September 11 Incident. International Relations Studies Quarterly 4 (17): 179–210.

مقصودی، محتبی. غله دار، ساحره. .1390. مشارکت زنان افغانستان در ساختار جدید قدرت پس از حادثه 11 سپتامبر. مطالعات روابط بین الملل، دوره 4. شماره 17. زمستان، صص 210-179.

Mahmoudi, Z. 2020. Perspectives and Scenarios of the Position of the Taliban in the Future Governance of Afghanistan (with an emphasis on media approaches). International Media 5 (6): 203–225.

محمودی، زهره. 1399. چشم انداز و سناریوهای جایگاه طالبان در عرصه حکمرانی آینده افغانستان، با تأکید بر رویکردهای رسانه ای. پژوهشنامه رسانه بین الملل. سال 5. شماره 6. صص 225-203.

Maizland, L. 2021. The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Realation. URL: www.cfr.org/backgrounder/taliban-Afghanistan.

Maley, W. 1998. Fundamentalism Reborn?: Afghanistan and the Taliban. New York: New York UP.

Maley, W. 2001. Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban. C. Hurst & Co.

Marsden, P. 2000. The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan. Translated by Kazem Firozmand. Tehran: Markaz.

مارسدن، پیتر. 1379. طالبان: جنگ، مذهب و نظم نوین در افغانستان، ترجمه کاظم فیروزمند. تهران: نشر مرکز.

Marzbani, F., and Amiri M. A. 2023. Investigating the Consequences of the Withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan on Iran's Issues. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 166–155). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

مرزبانی، فروزان. آخوندپور امیری، محمد. 1402. بررسی پیامدهای خروج ایالات متحده از افغانستان بر مسائل ایران»، در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اریبهشت. صص 166-155.

Matinuddin, K. 1999. The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997. Oxford University Press.

Moghaddas, A. 2021. The Study of Causes and Contexts of the Taliban's Return to Power in Afghanistan: A Three Level Analysis. Political Sociology of the Islamic World 2 (9): 55–82.

مقدس، اعظم. 1400. بررسی علل و زمینه های بازگشت طالبان به قدرت در افغانستان؛ یک تحلیل سه بعدی (2021-2015). جامعه شناسی سیاسی جهان اسلام، دوره 9. شماره 2. صص 82-55.

Moghim, M. H. 2023. The Role of the Fragility of the State on the Collapse of the Republic in Afghanistan. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 553–529). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

مقیم، محمدحارث. .1402. نقش شکنندگی دولت بر فروپاشی جمهوریت در افغانستان. در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اریبهشت. صص 553-529.

Mohaddesi, H. 2007. The Future of a Sacred Society: The Socio-Political Facilities and Perspectives of Religion in the Post-revolution Iran. The Quarterly Journal of Iranian Sociological Association 8 (1): 72–112.

محدثی، حسن. 1386. آینده جامعه قدسی: امکانات و چشم انداز اجتماعی – سیاسی دین در ایران پساانقلابی. جامعه شناسی ایران. دوره 8. شماره1، صص112-72.

Mohaddesi, H. 2019. God and Street: The Transcendental and the Socio-Political Order. 2nd ed. Tehran: Naghde Farhang.

محدثی، حسن. 1398. خدا و خیابان: نسبت امر متعال و نظم اجتماعی- سیاسی، چاپ دوم، تهران: نقد فرهنگ.

Mohammadi, M. 1998. Following the Sacred, in Love with the Secular: An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion in Iran. Tehran: Ghatreh.

محمدی، مجید. 1377. سر بر آستان قدسی، دل در گرو عرفی: درآمدی بر جامعه شناسی دین در ایران معاصر. تهران: قطره.

Mojdeh, V. 2003. Afghanistan and Five Years of Taliban Rule. Tehran: Nei.

مژده، وحید. 1382. افغانستان و پنج سال سلطه طالبان. تهران: نی.

Mojtabaiee, F. 1973. The Platonic Utopia and Kingdom. Tehran: The Cultural Association of Ancient Iran.

مجتبايي، فتح الله. 1352. شهر زيباي افلاطون و شاهي آرماني، تهران: انجمن فرهنگ ايران باستان.

Morshedizad, A. 2001. The Misfunction of Tradition and the Rise of the Taliban. Journal of the Book of the Month of Social Sciences 24 (41): 45–42.

مرشدی زاد، علی .1380. کژکارکردی سنت و ظهور طالیان. مجله کتاب ماه علوم اجتماعی. شماره 24-41. صص 45-42.

Nada, G. 2021. Iran, Afghanistan and the Taliban. Iranprimer, July 28, 2021. URL: https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2021/jul/28/iran-afghanistan-and-ta-liban.

Najafi, A. 2010. Ethnic, Cultural and Linguistic Diversity in Afghanistan. Regional Research 1 (5): 39–80.

نجفی، علی. 1389. تنوع قومی، فرهنگی و زبانی در افغانستان. پژوهش های منطقه ای. شماره5. صص 80-39.

Norouzi, M., Lavasani, S. A.-S., and Nazifi, N. 2023. Factors and Components of the Cycle of Fragility of the State and the Collapse of Political Systems in Afghanistan. Proceedings of the First National Conference of Afghanistan and Future Prospects, Alireza Pourrostam (collector), 27 April 2023 (pp. 288–265). Mashhad: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.

نوروزی، مجتبی. لواسانی، شکوه السادات و نظیفی نازنین. 1402. عوامل و مؤلفه های چرخه شکنندگی دولت و فروپاشی نظام های سیاسی در افغانستان، در: مجموعه مقالات اولین همایش ملی افغانستان و چشم اندازهای آینده، علیرضا پوررستم (گردآورنده) مشهد: دانشگاه فردوسی مشهد، 27 اریبهشت . صص 288-265.

Ouassini, A. 2018. Afghanistan: The Shifting Religio-Order and Islamic Democracy. Politics and Religion Journal 12 (2).

Pollowitz, G. 2014. The Taliban Warns ISIS of Being Too Extreme. National Review, December 31. URL: www.nationalreview.com/the-feed/taliban-warns-isis-being-too-extreme-gre....

Qandil, M. 2022. Challenges to Taliban Rule and Potential Impacts for Region. URL: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/challen-ges-taliban-rule-and-potential-impacts-r....

Qureshi, S. M. M. 1996. Pakhtunistan: The Frontier Dispute between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pacific Affairs 39 (1/2), Spring – Summer. URL: http:// ui.daneshlink.ir.

Rashid, A. 2000. Taliban; Islam, Oil and the New Big Game. Translated by Asadullah Shafaei and Sadegh Bagheri. Tehran: Danesh Hasti.

رشید، احمد. 1379. طالبان؛ اسلام، نفت و بازی بزرگ جدید، ترجمه اسدالله شفایی و صادق باقری، تهران: دانش هستی.

Rasouli, Y. 2016. The Irreversible Achievements of Women in Afghanistan. Contemporary Thought 2 (5): 339–360.

رسولی، یاسین. 1395. دستاوردهای برگشتپذیر زنان افغانستان. اندیشه معاصر. سال 2. شماره 5. صص 360-339 .

Rotberg, R. 2009. Failed States, Collapsed States, Weak States. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution Press.