Markets in Africa. The Example of Sapon Traditional Market: An Evolution of Cultural Values in the Spatial Planning of Oke-Ona, Abeokuta

скачать Авторы:

- Titilayo Elizabeth Anifowose - подписаться на статьи автора

- Teminijesu Isreal Oke - подписаться на статьи автора

- Olabode Ifetola Oyedele - подписаться на статьи автора

- Ayomipo Akintunde Fadeyi - подписаться на статьи автора

- Taiye Oladoyin Alagbe - подписаться на статьи автора

- Oluwatoyin Abiodun Adebayo - подписаться на статьи автора

Журнал: Social Evolution & History. Volume 24, Number 1 / March 2025 - подписаться на статьи журнала

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/seh/2025.01.05

Titilayo Elizabeth Anifowose, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

Teminijesu Isreal Oke, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

Olabode Ifetola Oyedele, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

Ayomipo Akintunde Fadeyi, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

Taiye Oladoyin Alagbe, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

Oluwatoyin Abiodun Adebayo, College of Environmental Science, Bells University of Technology Ota, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

Traditional markets are not merely places of trade; they play a crucial role in the cultural and economic fabric of African societies, serving as vibrant hubs for commerce, social interactions, and cultural exchange. Furthermore, they embody historical significance, community identity, and planning, especially in urban settings. In Abeokuta, towns such as Oke-Ona have traditional markets as integral parts of their spatial planning patterns, distinguishing them fr om modern urban structures. This study focuses on the Sapon market in Oke-Ona, Abeokuta, with the aim of identifying the cultural values that shape its spatial patterns. This study employs an inductive qualitative approach, using spatial analysis and other analytical methods, to explore the relationship between the traditional market and the urban layout of Oke-Ona. Using descriptive qualitative methods and in-depth interviews, this study highlights how the spatial values of the traditional space of Egba-Oke-Ona inform the market morphology. The findings reveal that: (1) The Sapon market is a historical element of Abeokuta's spatial layout and a crucial component of Oke-Ona town. (2) Oke-Ona is a traditional Yoruba town with a belief system that emphasises the harmony between the universe and human endeavours. It follows a tripod model in which the palace represents governance, the market represents economic activity, and the religious centre represents spiritual life. (3) The integration of the traditional market into the urban environment reflects the Sapon concept, illustrating its significance within both Oke-Ona and the larger Abeokuta urban areas. Despite the morphological changes since the establishment of the market, particularly in terms of the palace square and the size of the city, traditional values remain the primary drivers of these transitions.

Keywords: Abeokuta, cultural values, spatial morphology, spatial planning, traditional markets.

1. INTRODUCTION

The geographical location of the traditional market holds significant importance in the establishment of urban centres. Embedded within the urban framework, traditional markets play a multifaceted role. Markets provide affordable food and essential goods, particularly for low-income consumers, and act as critical entry points for smallholder farmers and street vendors (Davies et al. 2022). They foster economic development by creating employment opportunities, especially for women, and by supporting local economies through informal trade networks (Omeihe and Omeihe 2023; Cook et al. 2024). These markets serve as vital cultural spaces that reflect local heritage and community activities, preserving unique traditions amidst modern economic pressures, while facilitating social interactions and community bonding, thereby reinforcing cultural identity and continuity within rapidly urbanizing environments (Saharuddina et al. 2022; Cook et al. 2024).

These characteristic roles exhibited by markets foster intimacy and connections between traders and consumers (Rahadi 2012). The existence of traditional markets is intertwined with social advantages, such as cultural norms, belief systems, and economic transactions, which enhance interconnectedness and dependability among market participants (Andriani and Ali 2013). Dewey (1962) argued that within traditional market landscapes, a symbiotic relationship exists between commercial practices, societal norms, and economic structures. The conceptualisation of markets within contemporary settings, as exemplified by Dongdaemun in Korea, functions not only as a commercial hub, but also as an embodiment of the organizational structures among vendors and the social hierarchy that shape the interactions of market participants, which evolve to form a robust social fabric (Kim et al. 2004). Socio-economic activities and spatial configurations dictate the operational dynamics that determine patterns of movement. The proximity of residential areas to the city centre emerges as a pivotal element influencing the ease of access to various amenities and spaces that facilitate communal engagements (NÆss and Jensen 2004). Empirical evidence underscores the integrative role of traditional markets as integral components of cultural landscapes and communal spaces within urban environments where residents maintain and nurture social ties (Ekomadyo 2012). Several scholars have expounded on the pivotal role played by traditional markets as central nodes for local exchange of goods and services, which subsequently catalyze diverse activities within urban confines (Sirait 2006).

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. History and Role of Markets in Africa

2.1.1. Historical Development of Markets in Africa

The historical development of markets in Africa is a compelling narrative that spans fr om ancient times through the colonial period and in the post-colonial era, reflecting profound shifts in African societies. These markets, integral to the continent's socio-economic fabric, have evolved fr om simple barter systems to complex trade networks, adapting to the changing demands of their environment.

10. Pre-Colonial Era. In the pre-colonial era, African markets were pivotal to the continent's extensive trade networks, linking diverse communities across vast distances. These markets were often strategically located at crossroads, near rivers, or along major trade routes, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. For instance, the Swahili coastal markets, such as those at Kilwa and Zanzibar, were crucial in connecting Africa with the Arab world and Asia. These markets traded in gold, ivory, and slaves, among other goods, thus playing a significant role in global trade long before European colonization (Nyamnjoh 2003).

Similarly, the markets of West Africa, notably those along the trans-Saharan trade routes, were central to the economic and cultural life of cities like Timbuktu and Gao. These markets were not only commercial hubs but also centres of learning and cultural exchange, attracting scholars, traders, and travellers fr om all over the world (Hiskett 1994). The Hausa market towns of Kano and Katsina also exemplified the sophistication of pre-colonial African trade systems, where textiles, grains, and livestock were exchanged on a large scale (Aviat and Coeurdacier 2007).

2. Colonial Influence. The advent of colonialism brought significant disruption to African markets. Colonial powers imposed new economic systems and restructured the existing market practices to serve their interests. Indigenous markets that thrived under traditional systems faced competition fr om European imports and were subject to colonial regulations that often undermined their operations. For instance, in Nigeria, the British colonial administration restructured the markets in Lagos to better integrate them into the global economy, often at the expense of local traders (Dike 1956).

Colonial policies also led to the development of new market centres in urban areas, primarily designed to serve to the needs of colonial administrators and expatriates. These changes sometimes marginalise traditional markets, forcing them to adapt by incorporating new goods and practices. Despite these challenges, many markets remain resilient and continue to serve as vital economic and cultural centres. Markets such as Kejetia in Kumasi, Ghana, and Kurmi in Kano, Nigeria, managed to survive and even thrive during this period, maintaining their significance in the face of colonial pressures (Ranger and Hobsbawm 1984).

3. Post-Colonial Developments. At the end of colonial rule, many African countries sought to revitalise their economies by promoting local markets and indigenous economic practices. Markets that had been suppressed or marginalised during the colonial period, such as the Kumasi Central Market in Ghana and the Oshodi Market in Nigeria, experienced a revival. These markets have adapted to the new economic realities of independent African states and have become central to both rural and urban economies (Ahluwalia 2003).

However, the post-colonial period has also brought new challenges, including rapid urbanisation, economic liberalisation, and globalisation. Markets must evolve to meet the demands of modern economies while retaining their cultural significance. For instance, in East Africa, Maasai markets, which traditionally operated on a barter system, have adapted by incorporating cash transactions and modern goods, reflecting broader changes in the region's economy and culture (Kinyanjui 2019). These markets remain integral to African societies, providing a space where tradition and modernity intersect.

2.1.2. Role of Markets in African Societies

Markets in Africa play multiple roles and are deeply embedded in the socio-economic and cultural fabric of their communities. These roles can be broadly categorised into economic, social, cultural, and environmental dimensions.

1. Economic Roles. Markets are crucial to the economic landscape of many African societies, serving as the primary venues for the exchange of goods and services, especially in regions with underdeveloped formal retail infrastructure. Small-scale traders, many of whom are women, dominate these markets and rely on market activities as their main source of income. For instance, the Makola Market in Accra, Ghana, has long been a hub for the distribution of goods fr om rural areas to urban centres, providing a livelihood for thousands of traders (Pellow 1985). Similarly, the Dantokpa Market in Cotonou, Benin, serves as a regional trading hub, facilitating the flow of goods across borders and contributing significantly to the local economy (Meagher 1995).

Beyond the immediate exchange of goods, these markets support local agricultural production by providing a reliable outlet for farmers' production, thereby contributing to food security and rural development. Operating largely within the informal sector, these markets are critical for poverty alleviation, as they provide employment opportunities in areas with limited access to formal employment (Chant 2011).

2. Social and Cultural Roles. Markets are not just economic spaces but also vibrant centres of social and cultural life. They are places where people fr om diverse backgrounds come together, facilitating social interactions and strengthening community bonds. For example, the Ile-Ife Market in Osun, Nigeria, is deeply embedded in the cultural and religious fabric of the Yoruba people. It serves as a space wh ere cultural rituals are performed and traditional knowledge is passed down through generations (Adepegba 1991).

Moreover, markets like Ogunjimi in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, also play an important role in sustaining cultural heritage. This market is renowned for its role in preserving the cultural practices of the Akan people, wh ere traditional music, dance, and storytelling thrive (Arko-Mensah and Agyeiwaah 2024). Markets also foster community ties and cultural expression amidst the challenges of urbanisation, as seen in the Zongo Lane Market in Accra, Ghana, and the Jabi Lake Market in Abuja, Nigeria (Yankson and Bertrand 2012; Ajonye et al. 2016; Baidoo et al. 2024).

3. Environmental and Urban Planning Roles. Markets contribute to environmental sustainability by promoting the sale of locally produced goods, which reduces the carbon footprint associated with long-distance transportation, and supports the sustainable use of natural resources. Rural markets often emphasise seasonal and organic products, which are less resource intensive than mass-produced alternatives (Daneel 2011). Additionally, these markets are platforms for the exchange of indigenous knowledge on environmental conservation, with vendors sharing traditional practices related to sustainable farming and resource management (Fairhead and Leach 1996).

The role of markets in urban planning and development is increasingly recognised as African cities grapple with modernisation challenges. Markets such as the Maasai Market in Nairobi, Kenya, have become cultural landmarks and tourist attractions, showcasing the fusion of traditional and modern elements (Kamau 2015). However, the integration of these markets into modern urban landscapes presents challenges, including the need to balance market preservation with urban growth. Markets such as Oshodi in Lagos, Nigeria, have had to adapt to the pressures of urbanisation by expanding their physical infrastructure and incorporating digital technologies to remain competitive (Ikioda 2013).

African markets are dynamic institutions that have continuously adapted to the changing economic, social, and cultural landscapes of their societies. Although markets across the continent share common roles as economic and cultural hubs, their specific functions and structures vary widely, reflecting the diverse historical, social, and economic contexts in which they operate. African markets continue to evolve from the traditional layout of the Souk Semmarine in Marrakech, Morocco, to the modern business practices of the Jumia Market in Nairobi, balancing tradition with the demands of modern commerce. These markets remain vital to the continent's identity, embodying the resilience and adaptability of African societies.

2.2. Markets in the Traditional Economy of Nigeria

The presence of markets is a crucial feature of the traditional Nigerian economy, which functions as a venue for the transaction of goods between buyers and sellers. In sub-Saharan African societies, markets are prevalent for the sale of goods on a daily or periodic basis. Particularly in Nigeria, some of the agricultural produce of rural farmers is consumed locally, while the rest is traded in markets. It is often unfeasible for families in these societies to meet their agricultural needs independently. Consequently, surplus production is necessary to exchange goods that cannot be produced. Purwanto et al. (2021) delineated the market of traditional economy as a place exclusively for commercial transactions, also serving as a legal and communication hub. Ayittey (2006) characterised a market as an environment conducive to facilitating exchange. He postulated that regular exchange would lead to the emergence of a marketplace. Thus, the establishment of a marketplace is considered a natural process. In Nigeria, similar to other African countries, markets are categorised into two main types: local village markets and expansive markets that act as hubs for long-distance trade between regions (Oluwabamide 2003).

Rural markets in Nigeria are commonly located in open clearings. These markets cater to the needs of local producers, consumers, and traders while also attracting long-distance traders. While some rural markets operate daily, others function weekly, depending on the trade volume. The predominant goods traded in Nigerian rural communities include food items such as yam, cassava, plantain, salt, palm oil, banana, kola nuts, beans, and livestock such as goats, fowls, dried and smoked fish, and dogs (Onwuejeogwu 1975). Various types of fruit are sold in these marketplaces. The establishment of a market in many rural areas of Nigeria typically involves two key steps. The initial step entails gathering a consortium of traders on a regular basis, usually weekly, in an open area with some form of shelter. Initially, an individual entrepreneur may be tasked with clearing a designated open space. Should the market attract attendees from neighbouring communities, the village leader would then be summoned to formally sanction the operation of the market.

Rural markets in Nigeria are characterized by periodicity, as noted by Oluwabamide (2003). Market days were rotated among groups of villages, with the Yoruba following a 5-day cycle. Conversely, Ibo's rural markets adhere to a 4-day cycle or their multiples. This cycle system serves two purposes. According to Ayittey (2006), this arrangement responds to situations when the volume of goods for exchange is insufficient for daily trading. It also facilitates interactions between villages, stabilizes prices in neighbouring markets and redistributes supply. In Nigeria's rural markets, vendors are categorized based on the types of products they offer for sale. For instance, sellers of yams are positioned in a specific area of the market to encourage competition. This segregation extends to other commodities allowing customers to easily locate their desired goods, sel ect from a variety of products, and purchase at competitive prices because of the need for traders to outdo each other, as highlighted by Falola (1985) and referred to by Ayittey (2006). Certain Nigerian communities, particularly those within the Yoruba markets, are situated close to the palace of the Oba (King). These markets serve as sites for various rituals as documented by Fadipẹ et al. (1970). During traditional ceremonies, specific locations within the market are designated as sacrificial sites. It is believed that the Oba communicates with the spiritual realm during his nighty market visits. Every Yoruba community has an Oba market alongside other marketplaces.

2.3. The Traditional Market as a Component of Urban Design

The market represents a fiscal entity capable of bestowing value and prosperity upon human existence (Toni 2013). Its existence as a platform for the aggregation and distribution of production output has imbued significance in hastening the operational framework, mindset, and range of product types. In essence, markets serve as indicators

of shifts in the production, consumption, and circulation of commodities. Certain traditional markets reflect rural lifestyle patterns and are intrinsically linked to the occupational characteristics of the local community (Sunoko 2002). These traditional markets expand and evolve as hubs for the trade of goods and services are traded within a particular region, and subsequently stimulate diverse activities within an urban setting.

These activities include not only the exchange of goods and services or transactions, but also the sharing of information and knowledge (Ekomadyo 2012). This is in line with Geertz's assertion that a ‘market’ embodies an economic foundation and a way of life, encapsulating different facets of a particular society, including socio-cultural dimensions (Geertz 1963). Traditional markets serve not only as venues for commercial transactions, but also as embodiments of life philosophies and socio-cultural interactions (Pamardhi 1997). They reveal the societal fabric, characterised by the dominance of the social economy within the environment in which markets originate (Hayami 1987). According to Bromley (1978), traditional markets in Asian countries are situated in both rural and urban areas.

2.4. Traditional Marketplaces in the Urban Economic Structure

Traditional markets are perceived as a governance framework consisting of cohesive and interconnected proficient components, thus forming a complex unity that sustains each other. Within this context, the market structure encompasses various elements such as rotation, production, distribution, transport, and transactions, as stated by Nastiti (1995). Traditional markets are intertwined with numerous challenges that include financial and operational systems. Traders in traditional markets encounter many obstacles, including issues related to the delivery of goods, the provision of services, and the settlement of payments, whether with producers or consumers. Moreover, time and climate challenges are also prevalent. During such periods, merchants address these challenges by fostering relationships with intermediaries, consumers (who are also sellers), and sellers, including producers, distributors, and market authorities, as well as ‘goods carriers’. Furthermore, merchants persistently exert effort and cultivate frugal habits, while also engaging in religious enhancement within the merchant community, as highlighted by Sutami (2012).

2.5. The Scope of the Traditional Market Service

The market system typically culminates in a primary central settlement or other focal point, which ultimately facilitates the networking of markets. A market is a designated space or a specific area, with or without structures, used as a venue for commercial transactions. Sellers and buyers of goods gather in specific places at predetermined times and intervals (Jano 2006). Traditional urban markets have evolved into communal spaces, serving as places wh ere members of society gather and cultivate social bonds (Ekomadyo 2012). Within the realm of traditional markets, different roles are delineated, including vendors who are responsible for transporting goods between markets, those who handle sales to rural areas, individuals who manage wholesale transactions, and others who specialize in the sale of items, such as textiles, baskets, livestock, or grains (Geertz 1963). Traditional markets also uphold the social benefits engendered by the long-standing business ethos within these markets, serving as the fundamental code of conduct for vendors in their daily commercial endeavours through the preservation of values and norms such as honesty, reliability, cooperation between vendors and customers, and cooperation among vendors within traditional markets (Laksono 2009). Through advancements, traditional markets extend their reach to encompass a wider area pivotal hub for the exchange of goods and services on a regional scale, fostering growth and prompting diverse activities within urban centres (Sirait 2006).

3. METHODOLOGY

This study employed a qualitative naturalistic approach in its research methodology. This particular method is utilised to meet research needs which aim to identify unique characteristics or attributes that are not commonly found in research findings. The research involved a systematic examination of the behaviour and engagement of buyers and sellers within their environment, specifically in the Traditional Market. Additionally, the study focused on assessing the spatial capacity of the traditional market to facilitate these activities. Situated in Oke-Ona town, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria, this research focused specifically on the Sapon Market as an integral traditional urban element of Oke-Ona. The study began with the data collection phase, which involved the extraction of information through various means such as observation, structured and unstructured interviews, and content analysis, as outlined by Creswell and Creswell (2022).

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

4.1. History of Sapon Market in Oke-Ona Town

The people of Oke-Ona migrated to Ago-Oko in 1830, seeking refuge from the Oyo Empire and the Dahomey War.

The traditional square of Osinle held considerable power for the community and was used for various social and cultural activities, including festivals and events. At the same time, the Sapon market played a crucial role in economic endeavours. Chief Eboda Jimoh, known as the Apena of Oke-Ona, recognized Jagba in the Sapon market as the primary recreational centre from which Oke-Ona town originated. Originally situated just behind the Osinle palace building, this was the place wh ere people used to spend their leisure time in diverse social and cultural activities. Presently, it has been transformed into a residential zone. The Sapon market functioned as a gathering spot wh ere individuals, particularly unmarried men, came to indulge in the delicious bean porridge. This historically rich area remains the prominent commercial hub of Abeokuta city, linking Ijaiye, Ago-Oba, Itoku, Lafenwa, Isale Igbein, and Ake roads. It is currently crossed by an overhead bridge connecting these roads.

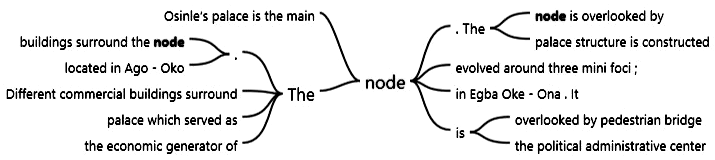

Despite the changes, Igbo traders and Yoruba women continue to display their merchandise daily. In 2017, the Sapon market was renamed Kemta Oloko market. The traditional square of Osinle, situated in Ago-Oko, serves as the primary palace in Oke-Ona, revolving around three central focal points: Osinle's palace square, the Sapon market, and the Motor Park, which has been repurposed as an Access Bank, surrounded by various commercial structures as shown in the Nvivo analysis flow in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Nvivo word tree analysis summarises

Osinle's palace character

Source: authors' analysis.

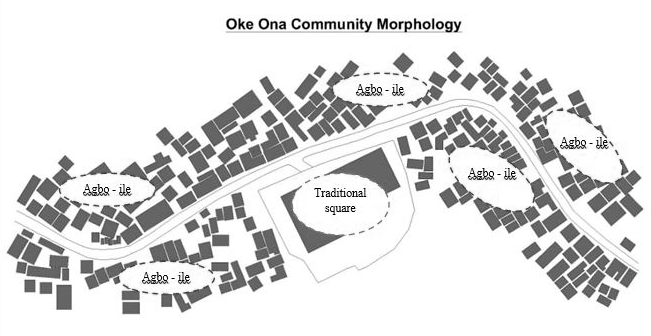

4.2. Structure of the Town of Oke Ona

Several cultural factors played a significant role in shaping the morphology of this square, such as topography, orientation, vegetation, political dynamics, socio-economic conditions, historical influences, and mythical origins. In addition, social gatherings, security measures, and defensive strategies were also contributing factors. The distinctive nucleated settlement layout, characteristic of the compact Yoruba Agbo-Ile system is evident in this square. The architectural structures were carefully planned in adherence to the Yoruba tradition of a radial settlement design, centred around three focal points: the Palace (for social and religious activities), the Market, and transit routes. These key elements defined the settlement arrangement of the Oke-Ona com-munity.

Historically, this traditional square served as a hub for administrative, social, religious, and economic affairs, embodying the Ebi philosophy. The organic development of the settlement can be observed primarily around the Osinle palace, crossroads paths, and ‘T’ junctions. In the Oke-Ona area, this is exemplified by the popular saying ‘Sapon lo re’, indicating the preference of bachelors to prepare an economical meal, especially potage beans, to show their wealth, as narrated by an elderly woman named Janet Olawuyi. The market place was aptly named Sapon lo re, reflecting local traditions. The topographical features of the area consist of low-lying terrain interspersed with hills. The strategic location of the palace square in the centre indicates its pivotal role, around which various activities revolved. This square symbolizes the locus of power and authority, while the market stands as the economic epicentre of the community.

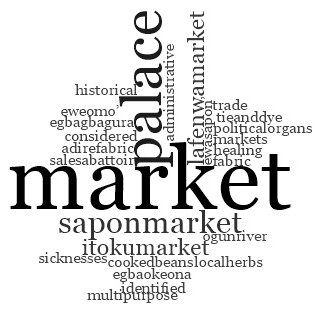

The Sapon market, identified with Oke-Ona, is recognized for its diverse functions. The traditional square not only embodies historical and religious significance, but also contributes to the tourism sector, whereas the Sapon market plays a pivotal role in the economic activities of the locality. However, the historical essence of the square has been somewhat overshadowed in recent times by the construction of the flyover. The settlement layout of Oke-Ona is characterized by a nucleated pattern, with the royal palace situated at its core. The association of Sapon market with Oke-Ona is primarily due to its versatile nature as a market space. Oke-Ona boasts of its proficiency in the production of tie and dye fabrics, particularly the famous Adire.

The palace, the market, and the Access Bank (a car park) are the three foci that illustrate the development of Oke-Ona (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Every urban fabric moves towards the direction of the traditional.

Fig. 2. Oke-Ona Traditional Square Morphology

Source: authors' sketch.

Fig. 3. Nvivo analysis in word cloud showing Sapon Market square

Source: authors' analysis.

4.3. Environmental Planning in Oke-Ona

On the western side of the palace building, one can find several vendor stalls, a recently constructed shopping complex, a branch of Access Bank, and a newly built bridge. To the right of the square edifice, there are secured shops designated for selling goods within the marketplace known as Sapon. Surrounding the square are a number of residential buildings comprising contemporary dwellings and traditional edifices, in addition to various financial institutions and the local post office. The Afomika stream, a site wh ere the annual worship of the Obatala deity takes place, is conveniently situated at a short distance from the square building.

4.4 The Traditional Square of Oke-Ona

Osinle's Palace, the principal residence of the Alake of Oke-Ona Egba situated in Ago-Oko, historically anchored the Oke-Ona area as a confluence of political power, economic activity at Sapon market, and transportation routes central to Abeokuta's development. The traditional square functioned as a hub for political and administrative activities, while the market played a crucial role as the primary economic hub for the traditional square. Recently, a pedestrian bridge has been constructed over the traditional square.

5. CONCLUSION

The Sapon Traditional Market in Oke-Ona, Abeokuta, has played an important role in the evolution of the community and its urban fabric over time. Economically, it serves as a major hub, supporting local livelihoods and facilitating the trade of diverse goods. Culturally, it acts as a vibrant space wh ere traditional practices and values are upheld, fostering social bonds and preserving Yoruba traditions. Socially, the market promotes community cohesion and integration, serving as a platform for interaction and information exchange. Additionally, in the context of urban development, the Sapon Market plays a crucial role in balancing modernization with the preservation of cultural heritage. While Sapon Market played roles similar to those of other traditional markets, several conclusions were drawn from this study regarding the underlying cultural values and spatial organization of Sapon Market.

First, the establishment of the market is deeply rooted in the astral-constitutional values of traditional Yoruba architecture. The authority of the palace plays a crucial role in maintaining these values, which persist in the clear delineation between sacred and secular spaces. This is particularly evident in the architectural layout of the market and the spatial arrangement of the stalls and kiosks.

Second, traditional market spatial patterns are strongly influenced by astral principles, with the location of shrines determined by the sacred/profane divide. This principle extends to smaller spatial configurations, such as the organization of individual stalls and kiosks within the market.

Finally, political and cultural factors have a significant impact on the geographical and spatial morphology of the market. Political considerations often dictate changes in the location and size of the market, while cultural shifts influence the relocation of shrines to better conform to cosmological principles.

The interplay of these cultural, political, and astral principles continues to shape the spatial dynamics of the Sapon Market, reflecting the enduring influence of traditional Yoruba architectural values.

REFERENCES

Adepegba, C. O. 1991. Yoruba Metal Sculpture. Ibadan University Press.

Arko-Mensah, A., and Agyeiwaah, V. 2024. Ancestral Roots for Cultural Education: Unpopular Musical Types in the Ashanti Community of Ghana for Musical Instruction. International Journal of Latest Research in Humanities and Social Science (IJLRHSS) 7 (3): 23–32. URL: www. ijlrhss.com.

Ahluwalia, P. 2003. The Wonder of the African Market: Post-Colonial Inflections. Pretexts: Literary and Cultural Studies 12 (2): 133–144. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/10155490320000166692.

Ajonye, S. E., Bello, I. E., Shaba, H., Asmau, I., and Khalid, S. 2016. Remote Sensing Assessment of Jabi Lake and its Environs: A Developmental Perspective. Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 1 (1): 1–8. URL: https://journals.aesacademy.org/index.php/aaes/article/view/aaes-01-01-01.

Andriani, M. N., and Ali, M. M. 2013. Kajian eksistensi pasar tradisional Kota Surakarta. Teknik PWK (Perencanaan Wilayah Kota) 2 (2): 252–269.

Aviat, A., and Coeurdacier, N. 2007. The Geography of Trade in Goods and Asset Holdings. Journal of International Economics 71 (1): 22–51. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2006.02.002.

Ayittey, G. 2006. Indigenous African Institutions. Brill Nijhoff. URL: https://brill.com/downloadpdf/display/title/14131.pdf.

Baidoo, I., Diaba, M. A., Atiwoto, A. E., and Sam, K. O. 2024. Economic Valuation of Three Selected Market Centers in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science 8 (3): 2590–2602.

Bromley, R. 1978. Traditional and Modern Change in the Growth of Systems of Market Centres in Highland Equador. In Smith, R. H. T. (ed.), Market-place Trade: Periodic Markets, Hawkers and Trades in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (pp. 31–47). Vancouver: University of British Columbia, Centre for Transportation Studies.

Chant, S. 2011. Meagher, K., 2010: Identity Economics: Social Networks and the Informal Economy in Nigeria. Oxford and Ibadan: James Currey and HEBN Publishers. Progress in Development Studies 11: 178–180. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100214.

Cook, B., Trevenen-Jones, A., and Sivasubramanian, B. 2024. Nutritional, Economic, Social, and Governance Implications of Traditional Food Markets for Vulnerable Populations in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Narrative Review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 8: 1382383.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. 2022. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications.

Daneel, M. L. 2011. Christian Mission and Earth-Care: An African Case Study. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 35 (3): 130–136. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/239693931103500304.

Davies, J., Blekking, J., Hannah, C., Zimmer, A., Joshi, N., Anderson, P., Chilenga, A., and Evans, T. 2022. Governance of Traditional Markets and Rural-Urban Food Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Habitat International 127: 102620.

Dewey, A. G. 1962. Trade and Social Control in Java. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 92 (2): 177–190.

Dike, K. O. 1956. Trade and Politics in the Niger Delta, 1830–1885: An Introduction to the Economic and Political History of Nigeria. Oxford University Press. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb02585.0001.001.

Ekomadyo, A. S. 2012. Menelusuri genius loci pasar tradisional sebagai ruang sosial urban di Nusantara. Semesta Arsitektur Nusantara 35.

Fadipẹ, N. A., Okediji, Q. O., and Okediji, F. O. 1970. Sociology of the Yoruba. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

Falola, T. 1985. Nigeria's Indigenous Economy. In Olaniyan, R. (ed.), Nigerian History and Culture (pp. 97–112). London: Longman.

Fairhead, J., and Leach, M. 1996. Enriching the Landscape: Social History and the Management of Transition Ecology in the Forest–Savanna Mosaic of the Republic of Guinea. Africa 66 (1): 14–36.

Geertz, C. 1963. Peddlers and Princes: Social Change and Economic Modernization in Two Indonesian Towns. University of Chicago Press.

Hayami, Y. 1987. Dilema Desa. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor.

Hiskett, M. 1994. The Course of Islam in Africa. Edinburgh University Press.

Ikioda, F. O. 2013. Urban Markets in Lagos, Nigeria. Geography Compass 7 (7): 517–526. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12057.

Jano, P. 2006. Public and Private Roles in Promoting Small Farmers Access to Traditional Market. Buenos Aires: IAMA.

Kamau, S. W. 2015. Crop-Land Suitability Using GIS and Remote Sensing In Nyandarua County, Kenya. URL: https://repository.dkut.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/370.

Kim, J. I., Lee, C. M., and Ahn, K. H. 2004. Dongdaemun, a Traditional Market Place Wearing a Modern Suit: The Importance of the Social Fabric in Physical Redevelopments. Habitat International 28 (1): 143–161.

Kinyanjui, M. N. 2019. African Markets and the Utu-Ubuntu Business Model: A Perspective on Economic Informality in Nairobi. African Minds. URL: https://doi.org/10.47622/9781928331780.

Laksono, B. G. 2009. Transnational Corporations and the Footwear Industry: Women in Jakarta. In Stoler, A. L., Redden, J., and Jackson, L. A. (eds.), Trade and Poverty Reduction in the Asia-Pacific Region: Case Studies and Lessons from Low-Income Communities (pp. 146–159). World Trade Organization.

Meagher, K. 1995. Crisis, Informalization and the Urban Informal Sector in Sub‐Saharan Africa. Development and Change 26 (2): 259–284. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1995.tb00552.x.

NÆss, P., and Jensen, O. B. 2004. Urban Structure Matters, even in a Small Town. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 47 (1): 35–57. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/0964056042000189790.

Nastiti, S. S. 1995. The Role of Markets in Java during Old Mataram Reign in the 8th – 9th Century. Jakarta: Indonesian University.

Nyamnjoh, F. 2003. Globalisation, Boundaries and Livelihoods: Perspectives on Africa. Philosophia Africana 6. URL: https://doi.org/10.5840/philafri-cana2003621.

Oluwabamide, A. J. 2003. Peoples of Nigeria and Their Cultural Heritage. Lisjohnson Resources Publishers.

Omeihe, K. O., and Omeihe, I. 2023. Notes on Historical Perspectives of Traditional Markets and Market Authority in African Systems: Evidence fr om Nigeria. In Omeihe, K. O., and Omeihe, I. (eds.), Contextualising African Studies: Challenges and the Way Forward (pp. 153–167). Emerald Publishing Limited. URL: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/978-1-80455-338-120231008/full/html.

Onwuejeogwu, M. A. 1975. The Social Anthropology of Africa: An Introduction. Heinemann. URL: http://archive.org/details/isbn_9780435897000.

Pamardhi, R. 1997. Planning for Traditional Javanese Markets in Yogyakarta Region. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Pellow, D. 1985. Sharing the Same Bowl: A Socioeconomic History of Women and Class in Accra, Ghana. JSTOR. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/481907.

Purwanto, H., Sidanti, H., and Kadi, D. C. A. 2021. Traditional Market Transformation into Digital Market (Indonesian traditional market research library). International Journal of Science, Technology & Management 2 (6): 1980–1988.

Rahadi, R. A. 2012. Factors Related to Repeat Consumption Behaviour: A Case Study in Traditional Market in Bandung and Surrounding Region. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 36: 529–539.

Ranger, T., and Hobsbawm, E. 1984. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge and New York.

Saharuddina, M. A.-H. M., Tazilana, A. S. M., Kamala, A. W. H., and Zbiecb, M. 2022. Kepentingan Peranan Pasar Tradisi dalam Konteks Bandar Warisan. 1 (5): 105–110. URL: https://doi.org/10.17576/jkukm-2022-si5(1)-11.

Sirait, T. S. 2006. Identifikasi Karakteristik Pasar Tradisional Yang Menyebabkan Kemacetan Lalu-Lintas Di Kota Semarang. Semarang: Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Engineering, Diponegoro University.

Sunoko, K. 2002. Perkembangan Tata Ruang Pasar Tradisional (Kasus Kajian Pasar-pasar Tradisional di Bantul). Yogyakarta: Universitas Gadjah Mada [PhD Thesis]. Thesis S2.

Sutami, W. D. 2012. Strategi rasional pedagang pasar tradisional. Jurnal Biokultur 1 (2): 127–148.

Toni, A. 2013. Eksistensi Pasar Tradisonal Dalam Menghadapi Pasar Modern Di Era Modernisasi. El-Wasathiya: Jurnal Studi Agama 1 (2). URL: http://ejournal.kopertais4.or.id/mataraman/index.php/washatiya/article/view/2311.

Yankson, P. W. K., and Bertrand, M. 2012. Challenges of Urbanization in Ghana. In Ardayfio-Schandorf, E., Yankson, P. W. K., and Bertrand, M. (eds.), Mobile City of Accra: Urban Families, Housing and Residential Practices. Counsel for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA).