Echo of the Arab Spring in Asia: A Quantitative Analysis

скачать Авторы:

- Korotayev, Andrey - подписаться на статьи автора

- Anastasia Shadrova - подписаться на статьи автора

- Elizaveta Sokovnina - подписаться на статьи автора

- Maria Kaygorodova - подписаться на статьи автора

- Musieva, Jamilya M. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Vasiliev A. - подписаться на статьи автора

Журнал: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 15, Number 1 / May 2024 - подписаться на статьи журнала

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2024.01.07

Andrey Korotayev, HSE University, Moscow, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia

Anastasia Shadrova, HSE University, Moscow, Russia

Elizaveta Sokovnina, HSE University, Moscow, Russia

Maria Kaygorodova, HSE University, Moscow, Russia

Jameelah Musieva, HSE University, Moscow, Russia; Lomonosov Moscow State University

Alexei Vasiliev, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia; Institute for African Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia; HSE University, Moscow, Russia

There is no doubt that the Arab Spring triggered a global wave of social and political destabilization which significantly exceeded the scale of the Arab Spring itself and affected all the world-system zones, including Asian countries.2 The analysis suggests that in the Asian region there were two waves of destabilization caused by the Arab Spring. The first started in 2011 and included a series of mostly peaceful protests, which had some features similar to the Middle Eastern revolutions in their organizational forms and communication methods. The second wave, in turn, took place in 2012–2014, when protest movements in Asia began to follow their own path, adding local discontent to their agenda. It was also connected with a sharp increase in terrorist activity in the Middle East, due to the weakening of several authoritarian governments and the emergence of consolidated terrorist organizations. Some Islamist groups in some Muslim-majority Asian countries, in their turn, pledged allegiance to these organizations (first of all, to ISIS/Daesh). Terrorist activity spread from the Arab world to Asia through various channels: the internationalization of jihadist ideas by militarized groups; ISIS propaganda on the Internet; refugees and jihadists returning to the region from the battlefields of the Arab World.

Keywords: protests, Asia, Arab Spring impact, terrorism, Islamism, China, South-East Asia.

Introduction

In 2011, it was impossible not to notice an unusually high intensity of socio-political destabilization across the whole world and especially in the Arab countries. The whole planet (including Asia) was swept by an exceptionally powerful wave of protest. Since the beginning of the Arab Spring, an explosive global growth has been observed for the vast majority of indicators of socio-political destabilization: anti-government demonstrations, riots, general strikes, terrorist/guerrilla attacks and political repression/purges. Moreover, against the background of a very noticeable decrease in the number of demonstrations, riots and strikes in the Arab World, there was a significant increase in their number in Asia, Western countries, Latin America (practically unaffected by the global destabilization wave in 2011), Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe in 2012–2015. This increase has more than offset the decline in the number of demonstrations, riots and strikes in the Arab World; and in 2014–2015 the global number of demonstrations, riots and strikes significantly exceeded the previous record levels of 2011 (Akaev et al. 2017; Korotayev, Meshcherina et al. 2017; Korotayev, Shishkina, and Lukh-manova 2017; Korotayev, Meshcherina, and Shishkina 2018; Korotayev, Romanov, and Medvedev 2019; 2022; Ortmans et al. 2017; Khokhlov et al. 2021).

The main goal of this article is to examine the possible connection between the Arab Spring and the wave of political destabilization in Asia in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century. To achieve this goal, we apply descriptive statistics to compare the dynamics of both unarmed protests and armed destabilization in the Arab World and Asia (as well as some other global macro-regions). This is combined with a qualitative analysis of the tactics, slogans, repertoires, organization, and agendas of the nonviolent and violent protests in Asia, which suggests a rather convincing connection with the Arab Spring.

The start of the Arab Spring is usually dated to 17 December 2010, when Mohammad Bouazizi, a young Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor, committed self-immolation in Sidi Bouzid, a provincial Tunisian town. This event triggered an explosive wave of protests in Tunisia which ended with a surprisingly swift collapse of the regime of the President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The main cause of this success is considered to be the (until then hidden) inter-elite conflict between the unprivileged army and the privileged security forces, which were under the special protection of the President (Nepstad 2011; Kuznetsov 2022). As a result, the army supported the protesters, and this led to the collapse of the authoritarian regime (these events came to be known as ‘Jasmine Revolution’). The surprisingly fast overthrow of Ben Ali encouraged secular leaders of youth organizations in Egypt and some other Arab countries to launch large-scale protests in their home countries, mostly via social media. Thus, the sudden youth protests in Egypt triggered an avalanche that led to the collapse of Hosni Mubarak's regime (Korotayev and Zinkina 2011, 2022; Korotayev, Issaev, and Shishkina 2016).

The above-mentioned events triggered a wave of destabilization throughout the Arab world, some signs of which, however, were already visible after the swift success of the Tunisian revolution. The extent of destabilization in certain countries depended mostly on the existence of favorable conditions in those countries, such as intra-elite conflict, partial authoritarian regime and whether it was based on a centralized or decentralized ruling coalition, the existence of unprivileged groups (except migrant workers), a high level of unemployment among young people (especially those with higher education), etc. (Holmes 2012; Beck 2014; Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur 2015; Keshavarzian 2014; Goldstone 2011; 2014; Grinin and Korotayev 2011; 2022; Howard and Muzammil 2013; Moore 2012; Korotayev, Issaev et al. 2022). In certain cases (notably Libya and Syria), external destabilizing factors played an important role. Researchers point out that the diffusion of the Arab Spring revolutions was more likely caused by international, rather than local, shocks (Gunitsky 2014; Grinin and Korotayev 2022). External factors were the ones to encourage the mobilization of new protest groups. Governments, in these cases, could only implement counter-diffusion tactics to prevent the formation of mobilization networks through all channels (Koesel and Bunce 2013).

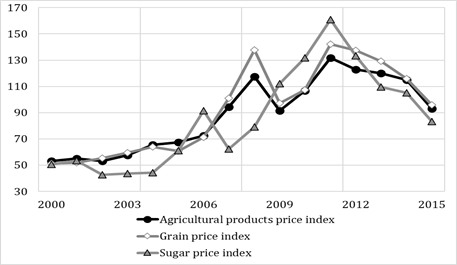

The researchers who study certain forms of socio-political destabilization base their explanatory models on internal processes which take place within a country or a region and tend to ignore external factors. For instance, when explaining Asian processes, political scientists often refer to economic crises and crises of democratic legitimacy and do not pay enough attention to the destabilizing effect of the Arab Spring. Here it should be noted that the problematic economic-political situation in the world in January and February 2011 was caused by agflation – an explosive increase in the prices of agricultural products. In turn, agflation became one of the factors that provoked socio-political destabilization in the Middle East region (Korotayev and Zinkina 2011; 2022). This aspect made the protest movement large-scale, as poorer segments directly affected by price growth joined the protests. In addition to the Middle East, other regions, including Asia, were affected by agflation, with prices of essential commodities rising. Thus, public outrage in the region combined with economic instability to provoke a political crisis (Sternberg 2012).

We would like to emphasize that we see the Arab Spring precisely as a trigger for the wave of global destabilization in 2011–2015, but not as its cause. A systematic consideration of the fundamental causes of the global wave is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to mentioning some of them. One of these causes seems to be the neoliberal monetary policy that the governments of the world's leading countries have been pursuing more and more systematically since the 1980s. This policy led to a significant increase in economic inequality and socio-structural tensions in countries at the core of the World System, which largely broke through in 2011 (Piketty 2014; Ortmans et al. 2017). On the other hand, the explosive growth of financial capital associated with this policy, together with the gradual liberalization of regulations, led to the global financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009 (Grinin and Korotayev 2010). The crisis had a global destabilizing effect not so much directly, but through the attempts (very successful in some respects), in the spirit of neoliberal monetarist theories, to get out of the crisis through a monetary policy of quantitative easing combined with a fiscal policy of reducing public spending (austerity). The result of these measures was an unprecedented global rise in food prices, accompanied with a squeeze on developing countries' finances, which in turn destabilized the periphery and semi-periphery of the World System.

In fact, it can be argued that the real trigger for the global political destabilization of the early 2010s was the global financial crisis of 2008 (see e.g. Korotayev, Shishkina and Khokhlova 2022). This had direct consequences for most of the regions discussed in this paper: Middle East, Asia, and the West. And then these interactions and inspirations between the Middle East revolutionary movements, the Occupy movements and Asia were in some respect only secondary, although the Arab Spring still acted as an immediate trigger of the global destabilization wave.

Considering the importance of the national context, socio-economic characteristics and local reasons for the outbreak of protest activity, it is possible to suggest that the revolutions in the Arab countries have had a significant effect on socio-political destabilization in Asian countries.

The aftermath of the Arab Spring was the most evident in China, where the youth protests of 2011 were very similar in form to the ‘Jasmine Revolution’ protests in Tunisia. However, researchers agree that despite similar organizational tactics and methods, the protests in China did not attract widespread interest and did not turn into a full-scale revolution (Hess 2013).

The spread of the protest movement in China had similar characteristics to the events of the Arab Spring, and began with the message exchange on the Internet, which appealed to the ongoing Jasmine Revolution (Mercury News 2011). Dissidents who lived abroad started to call the mainland Chinese to overthrow the regime via an opposition website, Boxun.com; later they also began using Twitter, following the example of the Arab countries (Hille 2011). Although the Chinese authorities blocked certain websites, the activists found ways to adapt to the new conditions and bypass the censorship (Fallows 2011). The main strategy of the opposition movement was to avoid the use of weapons and violence, and to use peaceful ways to show their protest spirit (Clemm 2011). The protesters held jasmine flowers or played a traditional song about jasmine on their mobile phones, thus emphasizing the importance of the national and historical component of their movement. According to the organizers, this helped people to criticize the current one-party government openly and fearlessly.

In other Asian countries, the echo of the Arab Spring have been much less impressive, and on a smaller scale. A famous opposition activist, Nguyen Dan Que was arrested in Vietnam in February 2011; he had taken the Arab Spring example and started calling on the Internet for the overthrow of the government and the formation of a new democratic and free country (Mason 2011). However, the protests in Vietnam did not spread.

Despite the fact that Vietnam did not repeat the Arab Spring events, in 2011–2012 there was a surge of protest movements, which is quite atypical for a communist country. For instance, in June 2011, hundreds of people went to the streets and started a demonstration in front of Chinese diplomatic missions to protest China's invasion of the disputed territories in the South China Sea (Vandenbrink 2014). Although the influence of the Arab Spring on events in Vietnam has not yet been thoroughly studied, there is circumstantial evidence on the connection between the protest movements surge and the events in the Arab region. The Vietnamese protesters used social media, including Twitter, to spread information and demand justice from the government. Ciorciari and Weiss consider the danger of nationalist movements in countries without democratic freedoms and also point out that the more authoritative a government is, the more difficult it is for it to suppress nationalist surges (Ciorciari and Weiss 2016). However, the connection between the Arab Spring and the events in Asia has not been considered in that paper.

There were also attempts to provoke protests in North Korea, which were reported by South Korean military guards. They dropped leaflets in North Korea with information about the protests in Egypt and Libya in an attempt to provoke political change in the DPRK. The central information agency of South Korea reported that the DPRK threatened military action if South Korea continued to drop leaflets inciting rebellion (Kim 2011).

In February 2011, a protest campaign mimicking the Egyptian scenario started in Myanmar. The actions were also coordinated through a Facebook page called ‘Just do it against the military dictatorship’ (Kaung 2011). Anti-government materials were distributed in several places throughout the country, including Mandalay and Taunggyi. More than 1,000 activists took part in the protest movement (Ibid.).

Furthermore, a direct connection can be established between the events in the Arab region and the protest movements in the Maldives that took place in 2011–2012 (Salam and Abdel 2015). The protests in the Maldives took place during the Arab Spring events and adopted a similar scenario. The protest movement was against the increase in prices and the poor economic situation in the country. The demonstrations and growing public outrage led to the impeachment of the President Nasheed's government in February 2012. In the international community, President Nasheed was nicknamed ‘The Godfather of the Arab Spring’, since his coming to power through public protests and government overthrow in 2008 resembled the Arab Spring events (Sattar 2012). However, after three years of economic recession, Nasheed's government proved to be inefficient and was forced to resign under the pressure from the protests.

The echo of the Arab Spring can also be traced in the Malaysian protests which started in June 2011. In this country, with a predominantly Muslim population, people followed the events of the Arab Spring with great interest. The people actively supported the new regimes in Egypt and Tunisia on social media (Bakar 2012). Opposition parties in Malaysia organized demonstrations in support of the new regimes in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. The following events can be used as examples of surges of public outrage in Malaysia: the Bersih 2.0 demonstration for fair and transparent elections in July 2011; the large pro-democratic protest movement Bersih 3.0; and the Popular Revolt in January 2013 (Postill 2014). The main characteristic of these events was the use of Facebook and Twitter as major communication tools of protesters (Radue 2012). Moreover, researchers point out that the excessive use of force by the government led to an increase in cross-ethnic and inter-generational engagement among the population in Malaysia, as it was the case in Tunisia and Egypt (Khoo 2014). Also, according to researchers, the Arab Spring events strengthened the connections between Malaysia, Egypt, and Tunisia, which resulted in the increase in the number of Malaysian students studying in these countries, and an influx of tourists from Arab countries to Malaysia (Albattat, Som and Ghaderi 2013).

It should also be taken into account that the Arab Spring affected the multiple Occupy movements which originated from the Occupy Wall Street movement in the USA that emerged under the direct influence of the Arab Spring and quickly spread throughout most parts of the world (Sergi and Vogiatzoglou 2014). Participants in the aforementioned movements openly declared that they were inspired by the protests in Arab countries (Slaughter 2011; Hammond 2015).

Skinner points to the similarity in methods between the activities of the Occupy protest movements and the protests of the Arab Spring (Skinner 2011). These include, for instance, the prolonged occupation of large areas (in particular, main city squares) by large crowds of protesters. There are also similarities in the slogans used by both the Arab protesters and the Occupy movement participants. In both cases, the protest agenda included demands for social and economic justice and genuine democracy, as well as aggressive anti-government rhetoric (Bogaert 2013). Furthermore, the impact of the Arab Spring on the Occupy movements was evident in the use of social media by protesters for mobilization and communication. Western protesters, like those in Tunisia and Egypt, actively used Facebook and Twitter hashtags (Kavada 2017).

The Asian region was no exception in terms of Occupy protests. The most prominent took place in Indonesia (in 2011), in Nepal, in Taiwan (student Sunflower Movement, 2014) and in Hong Kong (Umbrella movement, 2014) (Huat 2017).

Protests in Indonesia in September and October 2011 developed according to the Occupy Wall Street scenario and started with publications calling for action in Facebook groups (Oman-Reagan 2013). In particular, the events in Jakarta and the miners' strikes in West Papua resulted from intense activity by Indonesian cyber-activists. In 2011, 14 people were arrested as a result of protests against US coal mining activities (Amnesty International 2011). The governments of the USA and Indonesia considered the protests as a threat to the governments' collective security and identified participants in the Occupy movement as terrorists (Coll 2012).

Japan, on the other hand, had little resonance with the Occupy Wall Street movement, although it expressed its solidarity, by appealing to economic inequalities and expressing its opinion through the slogan ‘The 99 %’ (Saito 2012). In October, the Occupy Tokyo protests took place in three districts of the capital; but the movement did not gain enough popularity among the population and lasted only one day, overlapping with another topical protest movement related to the Fukushima accident.

The Indian reaction can also be considered as a ‘faint echo’ of the Arab Spring. On the one hand, some Indians supported the ideas of freedom and self-governance that led participants in the anti-corruption protests of 2011. On the other hand, India had its own political interests in Egypt, Bahrain, Oman, and Tunisia (Kumaraswamy et al. 2012). Thus, India's response to the protests in these countries can be defined as a ‘strategic silence’ in 2011, which showed itself in concern for the safety and well-being of Indian citizens in protesting regions; no support for the Arab protests movements was expressed. Nevertheless, several researchers point to the impact of the Arab Spring on the anti-corruption protests in India. Nigan argues that the Occupy movements and the Indian protests are united by similar anti-corruption slogans (Bhrashtahar Bharat Choro – Corruption Quit India!), which were able to mobilize different sections of the population. Werbner et al. (2014) note that the Indian movement was called the August Spring after the Arab Spring, and Montuori (2013), in turn, believes that the Indian protests resonated with the general wave of socio-political destabilization which started after the demonstrations in Egypt and Tunisia, and showed the creativity and solidarity developed by civil societies of these countries while fighting against exploitation and corruption (Werbner et al. 2014; Montuori 2013). Despite all this, the impact of the Arab Spring on the protests in India in 2011 is not obvious, because, firstly, the number of studies examining the connection between these two phenomena is very limited, and, secondly, the above-mentioned publications do not present substantiated evidence of an actual connection between the events.

The echoes of Arab Spring were felt on a much larger scale in India in December 2012, when the Nirbhaya movement spread to the country's capital, New Delhi, and in several other cities. Like Occupy Wall Street, this movement was decentralized and attracted people from different ideologies and social strata (Castells 2012). It was sparked by a case of sexual violence against a young woman by a group of people and, as a result, demands for severe punishment and stricter legislation in this sphere. Injustice against victims of sexual assault was also condemned (Harris and Kumar 2015; CNN 2013). The protest infrastructure had already been established during the 2011 anti-corruption protests and was used for the second time. The Indian protest adopted the tactic of using Twitter and Facebook, as this is where the mobilization and coordination of protesters took place with the help of hashtags (Ahmed and Jaidka 2013). Thus, it is after 2011 that one can speak of an echo of the ‘Arab Spring’ in India.

The protests in Nepal in December 2012, also known as Occupy Baluwatar, can be described as peaceful and with a unique agenda, which made them different from the rest of the Occupy movement. The main guide for the participants of the protest was the Nirbhaya demonstrations in India (Kumar, Jacobsen and Ku 2016). Inspired by the Indian movement, the Nepalese protesters, who were mostly students and youth, took to the streets to protest against the rape of a migrant woman by a police officer. Notably, after focusing on one case at first, the demonstrators later broadened their agenda to include general condemnation of violence against women, the impunity of rapists and the powerlessness of the authorities. The protest was coordinated through both emails and Twitter. The protesters also used creative techniques, for example, an interactive website, to attract a young audience and increase solidarity among the movement's participants.

It is important to note that the problem of the connection between the Arab Spring and the protest movement in Asia has not been thoroughly studied by specialists, and the Occupy movement is mostly being considered from a historical and political point of view. Thus, for instance, Ortmann, in his article on the ‘Umbrella revolution’ in Hong Kong in 2014, identifies several main reasons for protest democratic movements, the most important of which are the following: the slow process of democratic reforms due to the ruling elite, and the fragmentation of the democratic movement in Hong Kong since the 1980s (Ortmann 2015). On the other hand, Ho (2015) claims that the ‘Sunflower Movement’ in Taiwan started because of a tactical mistake by the government that provoked a wave of protests.

It turns out that the impact of the ‘Arab Spring’ on protest movements in the Asian region was complex. Participants of the 2011–2012 protests often used the experience of the Arab Spring participants and copied their organizational tactics, namely mobilization of protesters via social media. Many campaigns were aimed at supporting protesters in Middle Eastern countries. As for the agenda of protest activity in Asian countries, it included both discontent with economic measures and low living standards as a whole, and dissatisfaction with the government and political system.

But the Arab Spring also had a second echo, much bloodier than the first one. One of the consequences of the Arab Spring was the collapse or severe weakening of several fairly effective authoritarian regimes. In Libya, Syria, Yemen (and to some extent in Egypt), protracted internal conflicts began. Meanwhile, even before the Arab Spring, it had been shown that such a sharp weakening of the state organization (state failures) and the protracted internal conflicts associated with it create excellent conditions for the intensification of terrorist activities (Testas 2004; Piazza 2007; 2008a; 2008b; Campos and Gassenber 2009). The Arab Spring is simply no exception.

As Schumacher and Schraeder (2021) show, the leaders of Islamist terrorist organizations recognized as early as in 2011 that the revolutionary events of the Arab Spring had opened up opportunities for increased terrorist activity in the Middle East (Schumacher and Schraeder 2021). The weakening and transformation of political regimes in Libya, Yemen and Syria had the greatest impact on the expansion of terrorist activities. In Libya, a relatively strong authoritarian regime was replaced by an unstable, factional democratic regime, which eventually led to outbreak of the second wave of the Libyan civil war (Grinin, Korotyaev and Tausch 2019; Barmin 2022). The fall of the regime in Yemen led to the elimination of one of the main deterrent forces of terrorism in the Arabian South (Issaev et al. 2021). The dramatic weakening of the Assad regime in Syria in 2012–2013 led to the absence of effective state power in most of the vast non-regime-controlled territories of Syria (Wege 2015). On the border between Syria and Iraq (the main hotbed of terrorism before the Arab Spring), ideal conditions were created for the emergence of the jihadist Islamic State. As a result, a favorable situation for the growth and global spread of terrorist activity developed in the Arab countries. This led to a significant improvement in the ability of terrorist organizations of various kinds to act, a rapid increase in their strength, influence and the effectiveness of their organizational forms, which was realized after 2011 in an explosive global growth of terrorist activity (Abboud 2016; Baczko, Dorronsoro, and Quesnay 2017; Bandeira 2017; Blumi 2018; Simons 2016). This process took a certain amount of time, and this aspect of the influence of the Arab Spring on the World System manifested itself with a noticeable delay.

The Islamic State's influence was not limited to Syrian and Iraqi territories, as both Arab terrorist groups (from Libya, Yemen, Tunisia, Algeria, Jordan) and terrorist groups from some sub-Saharan African and Asian countries (the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia) pledged allegiance to it (Jalalzai 2015; Lefevre 2014; Weiss and Hassan 2016; Wolf 2013).

Since 2012, the protest wave in Asia started to subside, and at the same time it was accompanied by a wave of terrorist attacks, mostly conducted by groups related to global Islamist terrorist networks. In 2012 a series of large terrorist attacks happened: in India (the attack on Israeli diplomats in Delhi and four explosions in Pune), in Thailand (a series of explosions in Bangkok, Yala, and Hat Yai), in China (an attempted hijacking of a plane on the Hotan-Urumqi route, an attack in Echeng), etc. (Byatnal and Joshi 2012; Wongruang 2012). In 2013, terrorist attacks took place in Thailand, China, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Myanmar (Global Terrorism... 2023).

Militia groups in the Philippines were the first to pledge allegiance to the Islamic State in September 2014. Two large Muslim minority groups, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) and the Abu Sayyaf rebels, expressed their desire to fight for the Islamic State, which was documented in a video posted by Islamists on YouTube (Shay 2014). Later, in November 2014, several Indonesian Islamist terrorist groups pledge allegiance to the Islamic State and a year later formed the Jamaa Ansarut Daulah (JAD) alliance (Arianti and Singh 2015). Its purpose was to establish communication between Syrian jihadists and Indonesian rebels loyal to the Islamic State. In 2014, Malaysia also faced the threat of its citizens joining the Islamic State. The group arrested in Malaysia in the summer of 2014 claimed that the South-Eastern Caliphate had been formed, which was to encompass the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, and also told about their plans to go to Syria to learn from the Islamic State fighters (Daily Star Lebanon 2014; for background information see Aslam 2009a, 2009b; Shah 2006). Other countries in Asia, such as China, Thailand, and India, also faced the influence of the Islamic State. However, the extent of terrorist activity was lower, and fewer measures were taken to fight it than in Muslim-majority countries.

The oaths of the Philippine, Malaysian and Indonesian groups were recognized by the Islamic State only in 2016, when the Isnilon Hapilon of the ACG (Philippines-based Abu Sayyaf Group) was declared regional emir (Jadoon et al. 2020). The IS strategy of turning to Southeast Asia after losing territories in Iraq and Syria in 2016 and 2017 was further reinforced by the establishment of a new Wilayah (province), Sharq Asiya. It provided militants from diverse background with a unified ideological and physical platform from which to recruit them. The Islamic State has greatly facilitated the coordination of regional extremist organizations. For instance, Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), which is based in Indonesia, operates a unit in Malaysia that supports JI activities by providing funding, movement of money, and space for training. Malaysian militants also offered expertise and facilitated operations for the Basilan-based faction of the Abu Sayyaf Group (IPAC 2016). In order to effectively spread the IS's virulent extremist vision throughout the region's weak constituencies and attract more supporters, IS propagandists from both outside and inside the region increased their output on Malay-language social media, including IS's first Malay-language newspaper (Al-Fatihin).

In 2015 and 2016, the activity of terrorist organizations in Asia intensified, which was reflected in a wave of terrorist guerilla attacks. It is worth noting that despite the overall transnational connections of pro-Islamic State militants, the threat of their activity varies from country to country. The Philippines faced more complex terrorist attacks due to the groups' diversity and continuous instability, with different groups seeking independence and sharia law. In the Philippines, the series of terrorist attacks started with explosions at a bus park in 2015, killing one person and injuring 40 others. The attacks continued in the following years. For instance, Marawi, a predominantly Muslim city in Mindanao, was the target of an aggressive series of attacks by the ASG in May 2017 (ABS-SBN News… 2023). On the basis of some useful intelligence, fighting broke out when government forces attempted to arrest Isnilon Hapilon in Marawi. A community called Maluso was attacked by 60 to 100 ASG members in August 2017, killing nine people and wounding ten more (Mapping Militant Organizations… 2022). Guerilla attacks included clashes between ACG-Basilan units and the Philippine army, in which three soldiers and around ten ACG fighters were killed in 2015. Later, in 2016, the military again clashed with Isnilon fighters, this time killing eighteen soldiers.

Unlike the Philippines, Indonesia did not see the emergence of a united front of pro-Islamic State groups, although it had long-standing militant groups like JI and MIT. The loose network of Islamic State affiliates is known as Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), the most prominent group. It was behind the series of massive terrorist attacks – Surabaya bombings in 2018, which killed around 18 people and injured 40 (BBC 2018).

The chain of terrorist and guerilla attacks took place in other countries of Southeast Asia. In addition, Islamic State-affiliated groups were represented in India by about seven cells consisting of self-radicalized individuals and members of breakaway factions of militant groups such as SIMI and IM. In 2015, military formations in Kashmir that attacked Indian security forces were strengthened; a bus station and a police station were attacked in Gurdaspur in 2015; the Pathankot military airport was attacked and security personnel were killed in Pempor in 2016 (Panda 2016). A major terrorist attack took place in 2015, when a powerful explosion occurred at the Ratchaprasong intersection in Bangkok's business and tourist district. Terrorist attacks in the country continued in 2016, with around eight explosions and four arson attacks in tourist resorts. In January 2016, terrorists organized a shooting in downtown Jakarta, killing four Indonesians. Later, in July 2016, there was a terrorist attack in Kuala Lumpur, in which eight civilians were injured; in 2017, Indian pro-Islamic State groups carried out a bombing on the Bhopal–Ujjain passenger train that injured ten people (Avriel 2016; Beittel and Sullivan 2016; Gunaratna 2016; Hegghammer 2016; Zohar 2015).

The wave of terrorist attacks which took place in Asia followed the wave of political protests and contributed to increasing socio-political destabilization in the region.

The issue of the echo of the Arab Spring in Asia has been considered by researchers from various angles, including the issue of copying of protest organization and communication tactics. However, there is still a lack of research in which the direct correlation between the rise of protest movements in Asia and the events in the Arab region, which calls for a more in-depth study of this problem. At the same time, regional specificities and the role of various factors affecting destabilization should be taken into account.

Quantitative Analysis of Socio-Political Destabilization in Asia

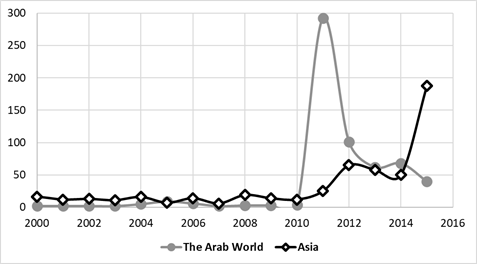

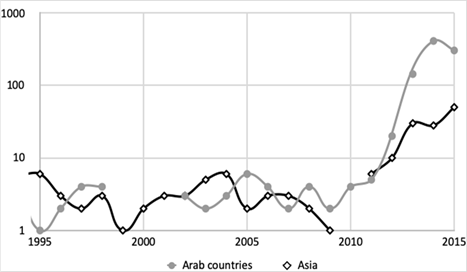

Consider the dynamics of the total number of major anti-government demonstrations and riots recorded in the Cross-National Time Series (CNTS) database (Banks and Wilson 2023) in Asian countries3 (see Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Dynamics of the total number of major anti-government demonstrations

recorded in the CNTS database in Asian countries4 and the Arab world, 2000–2015

Source: Banks and Wilson 2023.

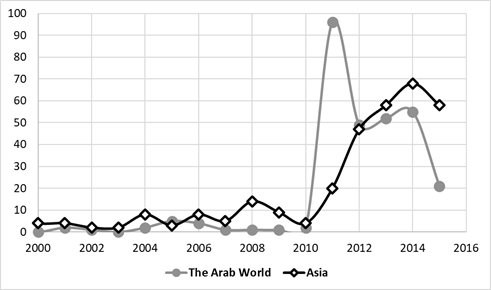

Fig. 2. Dynamics of the total number of major riots recorded in the CNTS database

in Asian countries and the Arab world, 2000–2015

Source: Banks and Wilson 2023.

The increase in the total number of anti-government demonstrations in Asia occurred with a certain lag in relation to the Arab Spring, but later grew to large proportions. In 2012 Asia broke its own historical record for this indicator; in 2013–2014, the number of demonstrations declined slightly, but remained at an unusually high level for Asia; and in 2015, Asia broke another record, outpacing all the other world regions in the number of major anti-government demonstrations.

As for riots, a pronounced increase in their number in Asia was already observed in 2011. It became significantly more pronounced in 2012 and continued in 2013–2014. Note that in 2014 Asia almost set its own local historical record, staying only slightly below the historical maximum of 1967 (see Figure 2). Moreover, in 2014 Asia contributed significantly to breaking the historical record for the world number of riots (see Figure 14 below).

The increase in the number of general strikes in Asia started one year later, in 2012, and in that year Asia set its own local historical record for this indicator. The next record was set in 2013, and another in 2015 (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Dynamics of the total number of general strikes recorded in the CNTS database

in Asian countries and the Arab World, 2000–2015

Source: Banks and Wilson 2023.

Note also that in 2015, Asia made the largest contribution to the historical record of the global number of general strikes (see Figure 14 below).

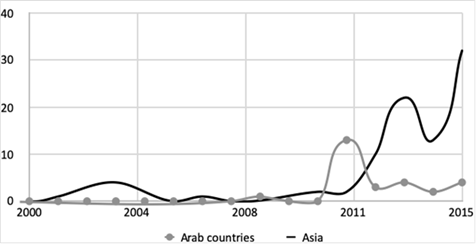

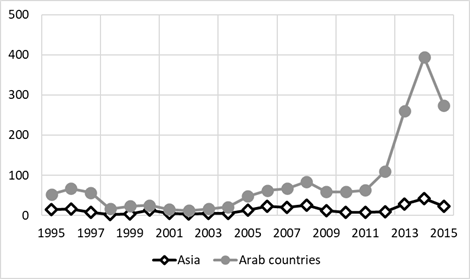

After 2012, the total number of major terrorist attacks/guerilla warfare actions in Asia also increased quite significantly (five times) (see Figures 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. Dynamics of the total number of major terrorist attacks/guerilla warfare

actions recorded by the CNTS database in Asian countries and the Arab world,

2000–2015, natural scale

Source: Banks and Wilson 2023.

Fig. 5. Dynamics of the total number of large terrorist attacks documented

in the CNTS database in Asian countries and the Arab world, 1995–2015,

logarithmic scale

Source: Banks and Wilson 2023.

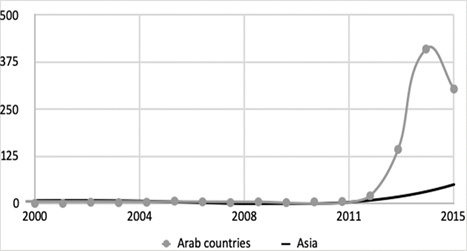

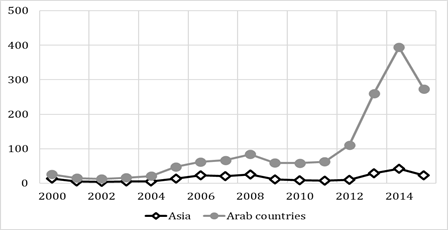

This is confirmed by the data from the Global Terrorism Database (see Figures 6 and 7).

Fig. 6. Dynamics of the total number of terrorist attacks documented by the Global

Terrorism Database (Start 2020) in Asian countries and the Arab world in 1995–2015

Fig. 7. Dynamics of the total number of terrorist attacks documented by the Global

Terrorism Database (beginning 2020) in Asian countries and the Arab world,

2000–2015

Moreover, the trend in the number of terrorist attacks in Asia (Figure 7) supports the hypothesis that the Arab Spring had a double ‘echo’. The first took place in 2011, and the second did in 2014.

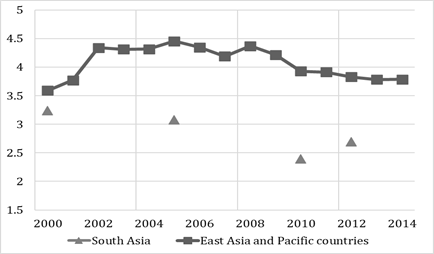

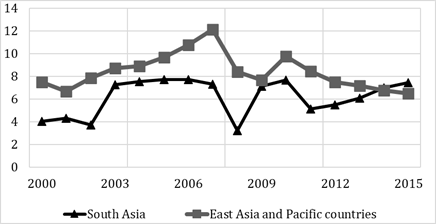

Finally, let us look at the factors behind the wave of destabilization in question. When analyzing the social and economic parameters, it can be seen (see Figure 8) that, unlike the Arab Spring, the unemployment factor did not play any important role in the Asian protests, since the unemployment rates in Asian and Pacific countries were 2.7 % and 3.7 % respectively, which is quite low.

Fig. 8. Unemployment in East Asia and the Pacific countries,

% of the labour force, average values, 2000–2014

Source: World Bank 2023.

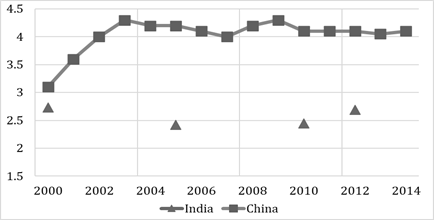

The same applies to the world's economic giants, represented by India and China, for which 2011 was not the year in which a sharp increase in the number of unemployed was observed (see Figure 9).

Fig. 9. Unemployment in India and China,

% of labor force, average values, 2000–2014

Source: World Bank 2023.

Speaking of economic factors that could have led to a strengthening of the Arab Spring echo in Asian countries, the GDP growth, which reflects the economic situation in a region, must be mentioned. As can be seen from the graph (Figure 10), South and East Asia saw a slight slowdown in GDP growth in 2011, but the growth rate levels remained quite high.

Fig. 10. GDP per capita growth rate in South and East Asia, %, 2000–2015

Source: World Bank 2020.

On the other hand, the so-called agflation (food inflation), the explosive increase in agricultural product prices, appears to have played here an important role. As can be seen in Figure 11, in 2010–2011 there was a rapid increase in agricultural prices around the world, which acted as a destabilizing factor.

Fig. 11. Annual price index for agricultural products, 2000–2015

Source: FAO 2023.

The Contribution of Asian Countries to the Global Wave of Destabilization:

Summary Analysis

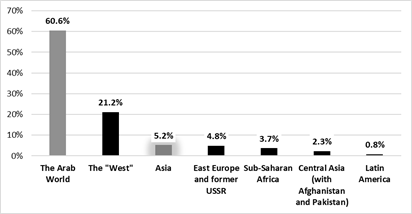

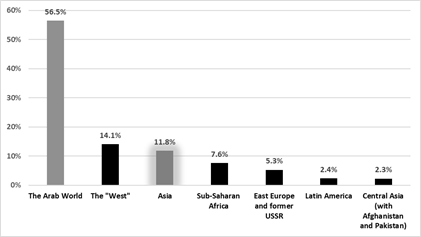

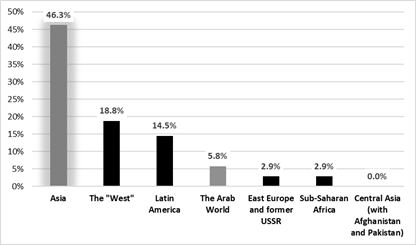

Now consider the comparative contribution of Asian countries to the global wave of destabilization triggered by the Arab Spring. The chart shows which world-system zones5 contributed most to breaking the global record for the number of major anti-government demonstrations in 2011 (see Figure 12).

Fig. 12. Contribution of different world-system macrozones

to the global destabilization of 2011 (anti-government demonstrations)

Obviously, the main contribution was made by Arab countries, but a significant contribution from Asian countries cannot be ignored.

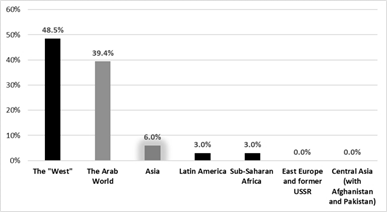

The situation was similar for the riots (see Figures 13 and 14). However, in this case the contribution of Western countries was much lower (still very high) and the contribution of Sub-Saharan Africa was much higher than in the case of anti-government demonstrations.

Fig. 13. Contribution of different World-System macrozones

to the global destabilization of 2011 (riots)

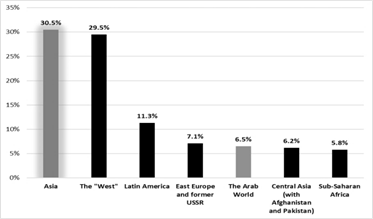

Fig. 14. Contribution of different World-System macrozones

to the global destabilization of 2011 (general strikes)

Speaking about the number of general strikes, the largest contribution was made by Western and Arab countries, while Asia once again took third place (see Figure 14).

It is noteworthy that during the further increase in the global number of anti-government demonstrations, riots, and political strikes that took place in 2014–2015, the contribution of Arab countries was almost non-existent. Other world-system zones took the lead.

For example, it was Asian countries6 that made the largest contribution to the peak (historical record) number of major anti-government demonstrations in 2015, accounting for more than 30 % of the total number (Figure 15).

Fig. 15. Contribution of different world-system zones to the historical record number of major anti-government demonstrations observed in the world in 2015

The unusually high number of major anti-government demonstrations in 2015 (compared to the period before 2011) was also observed in other world-system zones. However, each of these zones made a contribution that was smaller than that of Asian, Western and Latin American countries, but still significant.

Speaking of the contribution of different world-system zones to the global record number of riots in 2014 (see Figure 16), we can see that the difference between them is less pronounced. It is also worth noting the significant contribution of Asian countries, which are in the second place after the West.

Fig. 16. Contribution of different world-system zones to reaching

the peak

(historical record) number of riots globally in 2014

In terms of the global number of major general strikes in 2015, the contribution of different world-system zones was very uneven (see Figure 17). As can be seen, Asian countries played the central role, with almost half of the global number of general strikes in 2015 taking place on their territory.

Fig. 17. Contribution of different World-System macrozones to reaching the peak

(historical record) number of general strikes globally in 2015

As can be seen, in terms of indicators such as the global number of demonstrations, riots, and strikes, the contribution of different world-system zones to the global destabilization wave was uneven. In 2011, Arab and Western countries played a central role in the increase of these events. However, the role of Arab countries in further growth was decreasing, while the Asian influence was growing. To be precise, Asian countries contributed most to the global peak in the number of political strikes and large anti-government demonstrations in 2015. Asia was followed by Western countries and Latin America.

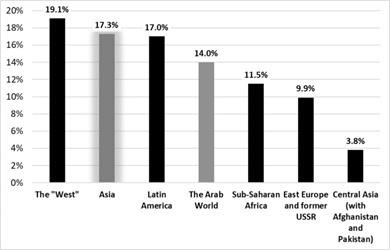

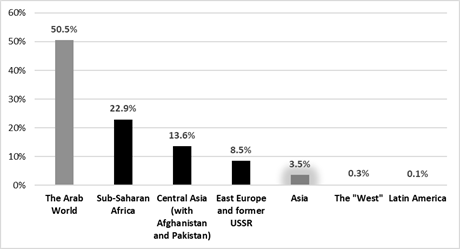

A very different picture can be observed with regard to a boom in the number of major terrorist attacks / ‘guerrilla warfare’ actions that took place in 2014 and were recorded by the CNTS system (see Figure 18). The overall picture is completely different here. The Arab world, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central Asia (including Afghanistan and Pakistan) were the main contributors to the historical record number of ‘guerilla warfare’ actions, in contrast to the picture for the global number of demonstrations, riots, and strikes. The Asian impact was also relatively low (3.5 %), compared to other world-system zones.

Fig. 18. Contribution of different world-system macrozones to the peak

(the historical record) of the global number of terrorist attacks /

‘guerrilla warfare’ actions in 2014

A remarkable pattern can be observed in here. The world-system zones whose contribution to the global number of terrorist attacks / ‘guerrilla warfare’ in 2014 was the lowest, set historical records in the number of major anti-government demonstrations, riots, and general strikes in 2014–2015. This refers to Asian countries (except the Middle East), Latin America, and the West.7 And, on the contrary, the world-system zones which contributed most to the historical record in the global number of terrorist attacks / ‘guerrilla warfare’ in 2014, showed relatively low numbers of major anti-government demonstrations, riots, and general strikes.

Thus, the wave of socio-political destabilization triggered by the events of the Arab Spring led to a significant increase in destabilization in the Asian region. In 2012–2013, there was a surge in the number of demonstrations and protests in Asia, followed by a new surge in 2015. The results confirmed the hypothesis of the impact of the Arab Spring on Asia, and showed that the echoes of the Arab Spring spread to regions far away from the Arab World.

Conclusion

The global wave of socio-political destabilization triggered by the Arab Spring led to a significant increase in socio-political instability in every single world-system zone. However, this wave manifested itself in different ways in different regions, and was also quite desynchronized.

The analysis we have conducted makes it possible to claim that the echoes of the Arab Spring reached Asia in two ways. The first could be observed starting from 2011 and was mainly represented by the rapid increase in anti-government demonstrations, riots, and general strikes. In terms of the number of general strikes, it was already in 2012 that Asia surpassed all previous historical records, which had been documented between the 1980s and the 2000s. The number of anti-government demonstrations, mostly in the form of peaceful protests, has fluctuated: it increased rather slowly in 2011, reached its historical peak in 2012, declined by 2014, and then rose sharply again in 2015. At the same time, the increase in the number of major anti-government demonstrations and political strikes in the year of the Arab Spring was not very high and did not even come close to the levels of the 1980s. On the other hand, the number of riots documented in Asia only in 2014 surpassed the previous record of the 1980s, but not that of the late 1960s. Thus, in 2011, the Arab Spring resonated in Asia mostly in the form of political strikes, which were also accompanied by an increase in anti-government demonstrations, some of which turned into riots.

It can be assumed that internal social and economic factors did not play a major role in the spread of political instability in Asia in the year of the Arab Spring, as the region experienced an economic recovery in 2010–2011. Accordingly, taking into account the available information on the direct influence of the Arab Spring events on the protest activity in Asia, the increase in the number of political strikes, anti-government demonstrations, and riots documented by the CNTS system in 2011 can be specifically linked to external factors such as the influence of the Arab Spring. Starting from 2012, the protest movement is Asia developed its own logic and continued at a fairly high level, reaching its peak in 2013, and then in 2015, despite the disappearance of the ‘Arab impulse’. A certain contribution to the maintenance of the high level of protest activity in Asia from 2012 onwards was made by the inertia factor and the ‘autocatalytic effect’ that is the effect of ‘contagion’ between the countries of the region, the main impulse of which came from China and India. It should be noted that the echo reached India with a delay, continuing the anti-corruption protests of 2011. Thus, the events in India can be defined as a ‘weak echo’ of the Arab Spring, but one that affected other countries in the region.

The second wave of the Arab Spring echo in Asia could be observed with a significant time lag in 2014–2015, however, terrorist organizations had been active ever since 2012. The consequences of the Arab Spring included the collapse or a sharp weakening of several quite efficient authoritarian regimes, which led to a sharp increase in the activity of various terrorist organizations, a rapid growth in their power, influence, and the efficiency of their organizational forms. Some Islamist groups in some Asian countries with high Muslim populations pledged allegiance to those organizations (primarily ISIS/Daesh). Terrorist activity spread from the Arab world to Asia through various channels: the internationalization of jihadist ideas by militarized groups; ISIS propaganda on the Internet; refugees and jihadists returning to the region from the battlefields of the Arab world. However, compared to the Arab countries, where the growth made a leap, it was not as explosive in Asia and did not break the historical records of the 1970s.

As noted above, the Arab Spring significantly stimulated the protest movements in Asia. Asian protest movements borrowed from the Middle East in terms of organizational forms and protest repertoires, tactics and slogans. However, authoritarian regimes also learned their lessons, for example by using social media to monitor and suppress dissent (Lynch 2016). On the other hand, as we could see above, the second echo was much less attractive, accompanied by the rise of radical Islamism and armed violence, chaos and civil wars, especially in Syria, Libya and Yemen; as a result, the Arab public ceased to support revolutionary experiments and movements.

Something similar was observed in Asia, but at the same time, Asian regimes were able to learn lessons and prepare in advance, and Asian publics were able to be more realistic or even pessimistic about the possible outcomes of protest movements and not support them in practice. Thus, the domino effect/social learning effect seems to have sup-ported revolutionary sentiment in the first phase, but it also inhibited revolutionary movements in the Middle East and Asia in the second.

And one final important remark. Our analysis suggests that in the early 2010s we were dealing with a revolutionary domino effect that was not confined to the Arab Middle East, but extended beyond the Middle East to Asia and other parts of the world. This reminds us of Huntington's theory of waves of democratization (Huntington 1993) that became rather popular in the early stages of the Arab Spring (e.g., Mansfield and Snyder 2012; Howard and Muzammil 2013; Stepan and Linz 2013; Abushouk 2016). However, in this context it seems appropriate to note that while Samuel Huntington paid great attention to the domino effect, he remained convinced that the domino effect of specific revolutions only works within certain cultural/civilizational areas and cannot transcend them, whereas our findings clearly contradict this point of view and show that the domino effect produced by the Arab Spring had a truly global scale, penetrating far beyond the borders of the Arab Islamic civilization and affecting all macro-regions of the world, including Asia.

NOTES

1 This research has been supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project № 19-18-00155).

2 It should be noted that when referring to ‘Asia’ in this research, we do not include the Middle East in Asia.

3 Excluding the Middle East and Central Asia.

4 Excluding the Middle East and Central Asia.

5 The classical world-system approach divides any world-system first of all into core, semi-periphery, and periphery (e.g., Wallerstein 1974; Wallerstein 2004). In what follows, the world-system core is denoted as ‘the West’, and its treatment as a separate entity has proved to be quite justified. However, it is clear that the periphery and especially the semi-periphery are very heterogeneous within the present-day World System; so for the analysis presented below they have been subdivided into macrozones (or, simply, zones). Our further analysis has shown that this subdivision makes perfect sense – different zones responded quite differently to the impulse of the Arab Spring.

6 It should be reminded that the ‘Asia’ aggregate does not include the countries of the Middle East and Central Asia.

7 However, as can be seen, the wave of terrorist attacks started to rise in the West from late 2015, as well. Suffice it to recall that in the Arab world, the wave of terrorist attacks rose significantly later than the wave of demonstrations, riots, and strikes.

REFERENCES

Abboud, S. N. 2016. Syria. Malden: Polity Press.

ABS-SBN News. 2023. TIMELINE: Maute Attack in Marawi City. ABS-SBN News 23.05. 2017 URL: https://news.abs-cbn.com/focus/05/23/17/timeline-maute-attack-in-marawi-city.

Abushouk, A. I. 2016. The Arab Spring: a fourth wave of democratization? Digest of Middle East Studies 25 (1): 52–69.

Ahmed, S. and Jaidka, K. 2013. Protests Against #delhigangrape on Twitter: Analyzing India's Arab Spring. eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government 1 (5): 28–58.

Akaev, A., Korotayev, A., Issaev, L. and Zinkina, J. 2017. Technological Development and Protest Waves: Arab Spring as a Trigger of the Global Phase Transition? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 116: 316–321.

Albattat, A. R. S., Som, A. P. M. and Ghaderi, Z. 2013. The Effect of the Arab Spring Revolution on the Malaysian Hospitality Industry. International Business Research 5 (6): 92–99.

Amnesty International. 2011. Indonesia: Release Participants of Peaceful Gathering in Papua. Amnesty International, October 20. URL: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa21/033/2011/en/.

Arianti, V., and Singh, J. 2015. ISIS’ Southeast Asia Unit: Raising the Security Threat. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. URL: https://hdl.handle.net/10356/80548.

Aslam, M. M. 2009a. A Critical Study of Kumpulan Militant Malaysia, its Wider Connections in the Region and the Implications of Radical Islam for the Stability of Southeast Asia. Victoria University of Wellington. URL:https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/41339479.pdf.

Aslam, M. M. 2009b. The Radical Islam in Southeast Asia: The Connections between the Malaysian Militant Group and Jemaah Islamiyah and Its Implications for Regional Security. International Journal of the Humanities 1 (7): 113–122.

Avriel, G. 2016. Terrorism 2.0: The Rise of the Civilitary Battlefield. Harvard National Security Journal 7: 199–239.

Baczko, A., Dorronsoro, G. and Quesnay, A. 2017. Civil War in Syria: Mobilization and Competing Social Orders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bakar, O. 2012. The Arab Spring: Malaysian Responses. Islam and Civilisational Renewal (ICR Journal) 4 (3): 743–746.

Bandeira, L. A. M. 2017. The Second Cold War. New York: Springer International Publishing.

Banks, A. S., Wilson, K. 2023. Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive. Jerusalem, Israel: Databanks International. URL: https://www.cntsdata.com/.

Barmin, Y. 2022. Revolution in Libya. In Goldstone J., Grinin L., Korotayev A. (eds.), Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change. Cham: Springer. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_28.

BBC. 2018. Surabaya Attacks: Family of Five Bomb Indonesia Police Headquarters. BBC. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-44105279.

Beck, C. J. 2014. Reflections on the Revolutionary Wave in 2011. Theory & Society 43 (2): 197–223.

Beissinger, M. R., Jamal, A. A. and Mazur, K. 2015. Explaining Divergent Revolutionary Coalitions. Regime Strategies and the Structuring of Participation in the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions. Comparative Politics 48 (1): 1–24.

Beittel, J. S., and Sullivan, M. P. 2016. Latin America: Terrorism Issues. CRS Report. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. URL: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/terror/RS21049.pdf.

Blumi, I. 2018. Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia tells us about the World. Oakland: University of California Press.

Bogaert, K. 2013. Contextualizing the Arab Revolts: The Politics behind Three Decades of Neoliberalism in the Arab world. Middle East Critique 3 (22): 213–234.

Byatnal, A. and Joshi, S. 2012. Four Low-intensity Blasts in Pune; One Injured. The Hindu. URL: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/four-low-intensity-blasts-in-pune-one-injured/ar....

Campos, N. F., and Gassenber, M. 2009. International Terrorism, Political Instability and the Escalation Effect. Discussion Paper No. 4061. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Castells, M. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons.

Ciorciari, J. D., and Weiss, J. C. 2016. Nationalist Protests, Government Responses, and the Risk of Escalation in Interstate Disputes. Security Studies 3 (25): 546–583.

Clemm, W. 2011. The Flowering of an Unconventional Revolution. South China Morning Post. International Edition. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20110305133754/; http://topics.scmp.com/news/china-news-watch/article/The-flowering-of-an-unconventional-revolution.

CNN. 2013. Is This the Start of India's ‘Arab Spring’? CNN 07.01.2013. URL: http://global-publicsquare.blogs.cnn.com/2013/01/07/is-this-the-start-of-indias-arab-spring/.

Coll, S. 2012. Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power. New York: Penguin Books.

Daily Star Lebanon. 2014. Malaysia ‘Foiled’ Attack Plots by ISIS-Inspired Militants. Daily Star Lebanon, August 20. URL: https://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2014/Aug-20/267773-malaysia-foiled-attack-plots-by-isi....

Fallows, J. 2011. Arab Spring, Chinese Winter. The Atlantic. URL: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/09/arab-spring-chinese-winter/8601/.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation). 2023. FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics. URL: http://faostat.fao.org/.

Global Terrorism Database 2023. [online]. Global Terrorism Database. College Park: University of Maryland. URL: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

Goldstone, J. A. 2011. Understanding the Revolutions of 2011. Foreign Affairs 3 (90): 8–16.

Goldstone, J. A. 2014. Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grinin, L. and Korotayev, A. 2010. Will the Global Crisis lead to Global Transformations? The Global Financial System: Pros and Cons. Journal of Globalization Studies 1 (1): 70–89.

Grinin, L. and Korotayev, A. 2011. The Coming Epoch of New Coalitions: Possible Scenarios of the Near Future. World Futures 67 (8): 531–563.

Grinin L., Korotayev A. 2022. The Arab Spring: Causes, Conditions, and Driving Forces. In Goldstone, J., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. (eds.), Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change (pp. 595–624). Cham: Springer.

Grinin, L., Korotayev, A. and Tausch, A. 2019, Islamism, Arab Spring and Democracy: World System and World Values Perspectives. Cham: Springer. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_23.

Gunaratna, R. 2016. Ivory Coast Attack: Africa's Terror Footprint Expands. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis 8 (6): 14–17.

Gunitsky, S. 2014. From Shocks to Waves: Hegemonic Transitions and Democratization in the Twentieth Century. International Organization 68 (3): 561–597.

Hammond, J. L. 2015. The Anarchism of Occupy Wall Street. Science & Society 79 (2): 288–313.

Harris, G. and Kumar, H. 2015. Clashes Break out in India at a Protest over a Rape Case [online]. The New York Times. URL:http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/23/world/asia/in-india-demonstrators-and-police-clash-at-protest-over....

Hegghammer, T. 2016. The Future of Jihadism in Europe: A Pessimistic View. Perspectives on Terrorism 10 (6): 156–170.

Hess, S. 2013. From the Arab Spring to the Chinese Winter: The Institutional Sources of Authoritarian Vulnerability and Resilience in Egypt, Tunisia, and China. International Political Science Review 34 (3): 254–272.

Hille, K. 2011. ‘Jasmine Revolutionaries’ Call for Weekly China Protests. The Financial Times. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/3ac349d0-3efe-11e0-834e-00144feabdc0#axzz2ExaYiEYN.

Ho, M.-Sh. 2015. Occupy Congress in Taiwan: Political Opportunity, Threat, and the Sunflower Movement. Journal of East Asian Studies 15 (1): 69–97.

Holmes, A. 2012. There Are Weeks When Decades Happen: Structure and Strategy in the Egyptian Revolution. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 17 (4): 391–410.

Howard, P. N. and Muzammil, M. H. 2013. Democracy's Fourth Wave? Digital Media and the Arab Spring. New York: Oxford University Press.

Huat, C. B. 2017. Introduction: Inter-referencing East Asian Occupy Movements. International Journal of Cultural Studies 20 (2): 121–126.

Huntington, S. P. 1993. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma press.

IPAC. 2016. Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia. Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict Report 33. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep07811.1.pdf.

Issaev, L., Khokhlova, A. and Korotayev, A. 2021. The Arab Spring in Yemen. In Goldstone J., Grinin L., Korotayev A. (eds.) Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change (pp. 685–705). Cham: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_26.

Jadoon, A., Jahanbani, N. and Willis, C. 2020. The Emergence of the Islamic State in Southeast Asia. In Rising in the East: A Regional Overview of the Islamic State's Operations in Southeast Asia (pp. 9–17). West Point: Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point.

Jalalzai, M. K. 2015. The Prospect of Nuclear Jihad in Pakistan: The Armed Forces, Islamic State, and the Threat of Chemical and Biological Terrorism. New York: Algora Publishing.

Kaung, B. 2011. Burmese Attempt Own ‘Facebook Revolution’ [online]. The Irrawaddy. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20110305011551/http://www.irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=20859.

Kavada, A. 2017. Social Movements and the Global Crisis: Organising Communication for Change. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 12 (1): 15–16.

Keshavarzian, A. 2014. Analyzing Authoritarianism in an Age of Uprisings. The Arab Studies Journal 22 (1): 342–357.

Khokhlov, N., Vasiliev, A., Belichenko, A., Kirdyankina, P. and Korotayev, A. 2021. Echo of Arab Spring in Western Europe: a quantitative analysis. Mezhdunarodnye Protsessy 19 (2): 21–49. Original in Russian (Хохлов Н., Васильев А., Беличенко А., Кирдянкина П., Коротаев А.. Эхо Арабской весны в Западной Европе: опыт количественного анализа. Международные процессы 19 (2): 21–49).

Khoo, Y. H. 2014. Mobilization Potential and Democratization Processes of the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih) in Malaysia: An Interview with Hishamuddin Rais. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 7 (1): 111–120.

Kim, H.-J. 2011. North Korea Threatens to attack South Korea, US [online]. The Washington Post. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/02/26/AR2011022604127.html.

Koesel, K. J., and Bunce V. J. 2013. Diffusion-Proofing: Russian and Chinese Responses to Waves of Popular Mobilizations against Authoritarian Rulers. Perspectives on Politics 11 (3): 753–768.

Korotayev, A., Issaev, L., and Shishkina, A. 2016. Egyptian Coup of 2013: an ‘Econometric’ Analysis. The Journal of North African Studies 21 (3): 341–356.

Korotayev, A., Issaev, L., Malkov, S., and Shishkina, A. 2022. The Arab Spring: A Quantitative Analysis. In Goldstone, J., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. (eds.), Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change (pp. 781–810). Cham: Springer.

Korotayev, A., Meshcherina, K. and Shishkina, A. 2018. A Wave of Global Sociopolitical Destabilization of the 2010s: A Quantitative Analysis. Democracy and Security 14 (4): 331–357.

Korotayev, A., Meshcherina, K., Kulikova, E. and Delyanov, V. 2017. Arab Spring and its Global Echo: Quantitative Analysis. Sravnitelnaya Politika-Comparative Politics 8 (4): 113–126. Original in Russian (Коротаев А. В. Мещерина К. В. Куликова Е. Д., Дельянов В. Г. Арабская весна и её глобальное эхо: количественный анализ. Сравнительная политика 8 (4): 113–126).

Korotayev, A., Shishkina, A. and Lukhmanova, Z. 2017. The Global Socio-Political Destabilization Wave of 2011 and the Following Years: A Quantitative Analysis. Polis-Politicheskiye Issledovaniya 6: 150–168. Original in Russian (Коротаев А. В., Шишкина А. Р., Лухманова З. Т. Волна глобальной социально-политической дестабилизации 2011–2015 гг.: количественный анализ. Полис. Политические исследования 6: 150–168. https://doi.org/10.17976/jpps/2017.06.11).

Korotayev, A., Romanov, D. and Medvedev, I. 2019. Echo of the Arab Spring in Eastern Europe: A Quantitative Analysis. Sociologiceskoe Obozrenie 18 (1): 56–106. DOI: 10.17323/1728-192x-2019-1-56-106.

Korotayev, A., Shishkina and A, Khokhlova, A. 2022. Global Echo of the Arab Spring. In Goldstone, J., Grinin L., and Korotayev A. (eds.), Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change (pp. 813–849). Cham: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_31.

Korotayev, A., Zinkina, J. 2011. Egyptian Revolution: A Demographic Structural Analysis. Entelequia. Revista Interdisciplinar 13: 139–169.

Korotayev, A., Zinkina, J. 2022. Egypt's 2011 Revolution. A Demographic Structural Analysis. In: Goldstone J., Grinin L., Korotayev A. (eds.) Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change (pp. 651–683). Cham: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-86468-2_25.

Kumar, S., Jacobsen, S. and Ku E. 2016. Cultures of Peace in India: Local Visions, Global Values and Possibilities for Social Change. Peaceworks 1 (6): 1–13.

Kumaraswamy, A., Mudambi, R., Saranga, H., and Tripathy, A. 2012. Catch-up Strategies in the Indian Auto Components Industry: Domestic Firms’ Responses to Market Liberalization. Journal of International Business Studies 43 (4): 368–395.

Kuznetsov, V. 2022. The Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia and the birth of the Arab Spring uprisings. In Goldstone J. A., Grinin L., Korotayev A. (eds.), Handbook of Revolutions in the 21st Century: The New Waves of Revolutions, and the Causes and Effects of Disruptive Political Change. Cham: Springer.

Lefevre, R. 2014. Is the Islamic State on the Rise in North Africa? The Journal of North African Studies 19 (5): 852–856.

Lynch, M. 2016. The New Arab Wars: Uprisings and Anarchy in the Middle East. New York: Public Affairs.

Mansfield, E. D. and Snyder, J. 2012. Democratization and the Arab Spring. International Interactions 38 (5): 722–733.

Mapping Militant Organizations. 2022. Abu Sayyaf Group. Stanford: Stanford University. URL: https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/abu-sayyaf-group.

Mason, M. 2011. Vietnam Dissident Detained for Revolution Calls. Washington Post, February 28. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/02/28/AR2011022800803.html.

Mercury News. 2011. China Cracks down on Call for ‘Jasmine Revolution’. Mercury News, February 19. URL: https://www.mercurynews.com/2011/02/19/china-cracks-down-on-call-for-jasmine-revolution/.

Montuori, A. 2013. Creativity and the Arab Spring. East-West Affairs 1: 30–47.

Moore, E. 2012. Was the Arab Spring a Regional Response to Globalization? E-International Relations. URL: http://www.e-ir.info/2012/07/02/was-the-arab-spring-a-regional-response-to-globalisation/.

Nepstad, S. E. 2011. Nonviolent Resistance in the Arab Spring: The Critical Role of Military-Opposition Alliances. Swiss Political Science Review 17 (4): 485–491.

Oman-Reagan, M. P. 2013. Occupying Cyberspace: Indonesian Cyberactivists and Occupy Wall Street. Doctoral dissertation for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology. New York: The City University of New York.

Ortmann, S. 2015. The Umbrella Movement and Hong Kong's Protracted Democratization Process. Asian Affairs 46 (1): 32–50.

Ortmans, O., Mazzeo, E., Meshcherina, K., and Korotayev, A. 2017. Modeling Social Pressures toward Political Instability in the United Kingdom after 1960: A Demographic Structural Analysis. Cliodynamics 8 (2): 113–158.

Panda, A. 2016. Gurdaspur, Pathankot, and Now Uri: What Are India's Options? The Diplomat 9. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/gurdaspur-pathankot-and-now-uri-what-are-indias-options/.

Piazza, J. A. 2007. Draining the Swamp: Democracy Promotion, State Failure, and Terrorism in 19 Middle Eastern Countries. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 30 (6): 521–539.

Piazza, J. A. 2008a. Do Democracy and Free Markets Protect us from Terrorism? International Politics 45 (1): 72–91.

Piazza, J. A. 2008b. Incubators of Terror: Do Failed and Failing States Promote Transnational Terrorism? International Studies Quarterly 52 (3): 469–488.

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Postill, J. J. 2014. A Critical History of Internet Activism and Social Protest in Malaysia, 1998–2011. Asiascape: Digital Asia 1 (1–2): 78–103.

Radue, M. 2012. The Internet's Role in the Bersih Movement in Malaysia –A Case Study. International Review of Information Ethics 18: 60–70.

Saito, H. 2012. The Fukushima Disaster and Japan's Occupy Movement. Possible Futures, February 28. URL: http://www.possible-futures.org/2012/02/28/fukushima-disaster-japans-occupy-movement/.

Salam, E. and Abdel, A. 2015. The Arab Spring: Its Origins, Evolution and Consequences… Four Years on. Intellectual Discourse 23 (1): 119–139.

Sattar M. 2012. Maldives coup: Mohamed Nasheed, Godfather of the Arab Spring, Falls from Grace. The World Global Post, February 15. URL: https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-02-15/maldives-coup-mohamed-nasheed-godfather-arab-spring-falls-gra....

Schumacher, M. J., and Schraeder, P. J. 2021. Does Domestic Political Instability Foster Terrorism? Global Evidence from the Arab Spring Era (2011–2014). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 44 (3): 198–222.

Sergi, V., and Vogiatzoglou, M. 2014. Think Globally, Act Locally? Symbolic Memory and Global Repertoires in the Tunisian Upraity Mobilizations. In Fominaya C. F., Cox L. (eds.), Understanding European Movements: New Social Movements, Global Justice Struggles, Anti-austerity Protest (pp. 220–235). London: Routledge.

Shah, M. Sh. H. 2006. Terrorism in Malaysia: An Investigation into Jemaah Islamiah. PhD thesis. Exeter: University of Exeter.

Shay, S. 2014. The Islamic State and its Allies in Southeast Asia. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism. URL: http://www.ict.org.il/Article/1238/The-Islamic-State-and-its-Allies-in-Southeast-Asia#gsc.tab=0.

Simons, G. 2016. Islamic Extremism and the War for Hearts and Minds. Global Affairs 2 (1): 91–99.

Skinner, J. 2011. Social Media and Revolution: The Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement as Seen through Three Information Studies Paradigms. Working Papers on Information Systems 11 (169): 2–26.

Slaughter, A.-M. 2011. Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring. The Atlantic 10. URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/10/occupy-wall-street-and-the-arab-spring/246....

Stepan, A. and Linz, J. J. 2013. Democratization theory and the ‘Arab Spring’. Journal of Democracy 24 (2): 15–30.

Sternberg, T. 2012. Chinese Drought, Bread and the Arab Spring. Applied Geography 34: 519–524.

Testas, A. 2004. Determinants of Terrorism in the Muslim World: An Empirical Cross-Sectional Analysis. Terrorism and Political Violence 16 (2): 253–273.

Vandenbrink, R. 2014. Anti-China Protests in Vietnam Turn Deadly. Radio Free Asia. URL: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5391ba0a14.html.

Wallerstein, I. 1974. The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

Wallerstein, I. 2004. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wege, C. 2015. Urban and Rural Militia Organizations in Syria's Less Governed Spaces. Journal of Terrorism Research 6 (3): 35–61.

Weiss, M., and Hassan, H. 2016. ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. 2nd ed. New York: Regan Arts.

Werbner, P., Webb, M. and Spellman-Poots, K. 2014. The Political Aesthetics of Global Protest: the Arab Spring and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Wolf, A. 2013. An Islamist ‘Renaissance’? Religion and Politics in Post-revolutionary Tunisia. The Journal of North African Studies 18 (4): 560–573.

Wongruang, P. 2012. Suspects Partied in Pattaya. Bangkok Post. URL: https://www.bangkok-post.com/thailand/general/280201/suspects-partied-in-pattaya.

World Bank. 2023. World Development Indicators Online. Washington, DC: World Bank. URL: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

Zohar, E. 2015. The Arming of Non-State Actors in the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula. Australian Journal of International Affairs 69 (4): 438–461.