Protest Dynamics in the Global Context

скачать Авторы:

- Ustyuzhanin, Vadim V. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Medvedev, Ilya A. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Ufimtsev, Andrey I. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Sumernikov, Ilya A. - подписаться на статьи автора

- Musieva, Jamilya M. - подписаться на статьи автора

Журнал: Journal of Globalization Studies. Volume 14, Number 2 / November 2023 - подписаться на статьи журнала

DOI: https://doi.org/10.30884/jogs/2023.02.10

Vadim V. Ustyuzhanin, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Ilya A. Medvedev, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Andrey I. Ufimtsev, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Ilya A. Sumernikov, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow

Jamilya M. Musieva, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow; Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow

At a time of growing socio-political instability, the analysis of the numerous protests taking place around the world is becoming of the utmost interest. This article focuses on the dynamics of non-violent destabilization processes, which are becoming increasingly dominant even in developing countries and less developed regions with many socio-economic and political problems. The authors provide empirical data on non-violent protest activity based on the Global Protest Database, which consists of a huge number of media in nine languages and is presented in the Google News aggregator. With a list of more than 520,000 articles in nine languages from January 2005 to December 2021, the authors standardized all the data on the number of news sources per month, and then used the principal component method to aggregate the information into a variable that can be considered as an index of protest activity. The observed value of the index for each month and trends are presented in the article.

This study was supported by strategic project ‘National Centre for Science, Technology and Socio-Economic Foresight’ of Higher School of Economics integrated development programme.

Keywords: protests, global protest database, destabilization.

Introduction

After 2011, the world witnessed an explosive growth of socio-political instability, largely due to the huge increase in the number of protests (Korotayev et al. 2018). At the same time, such a wave of mainly non-violent destabilization* affected not only countries in the Middle East and Africa, but the whole world. Mass protests and even revolutionary episodes began in many developed countries that had been considered quite resistant to instability.

Such a rapid increase in the number of protests naturally prompted researchers to review existing theories and conduct new studies. However, two important components were missing. First, there are no models for analyzing and predicting non-violent destabilization, while violent episodes are fairly well studied (Blair and Sambanis 2020; Fearon and Laitin 2003; Goldsmith et al. 2013; Hegre et al. 2013). There are also models for predicting and analyzing general levels of instability (Kennedy 2015; King and Zeng 2001), however, their main shortcoming is that they often ‘assume that the absence of violence is equivalent to the absence of conflict’ (Day et al. 2015: 129), and as the share of non-violence in general political instability gradually increases, their explanatory models lose relevance (e.g., an analysis of the model of Jack Goldstone et al. [2010] over time can be found in [Bowlsby et al. 2020]). Second, there is a lack of complete empirical data on the dynamics of instability. This is particularly true of protest activity, which is one of the most widespread and ‘incalculable’ forms of instability. On the one hand, the number of different sources of information, databases on protest activity, is quite large, but most of them are manually collected on the bases of traditional media, which creates a certain time lag between the event and its entry into the database and does not allow one to quickly react to changes in dynamics. In addition, manually collected sources have rather large and well-known problems, the main ones being subject bias, low information coverage and the prohibitively high cost of constantly updating information (Day et al. 2015; Jenkins and Maher 2016; Rafail et al. 2019). In many ways, this is why some researchers have decided to move to an entirely new way of collecting data – one that is automated and requires much less human involvement. The idea of creating such databases began to develop in a subfield of political science, such as PEA (protest event analysis), after the big data revolution, when a huge amount of information began to get and stay on the Internet. In other words, every event has a digital footprint that can be tracked, allowing researchers opportunities to explore and collect empirical data. However, such automated databases are, firstly, almost never used, and secondly, they have their drawbacks, the most important of which is the English bias, that is, the reliance mainly on the most numerous English-language sources.

This paper presents a new global protest database in which the authors have attempted to overcome the problem of English bias by collecting information on protest activity from sources in nine languages – English, Arabic, Chinese (Mandarin), Hindi, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German and Russian. The variety of languages used is necessary to respond to the significant globalization of destabilization. Global economic crises, food shortages, the growth of ethnic and confessional contradictions, and energy shortages are signs that the triggers of destabilization are becoming global and can influence protests and, more specifically, revolutions (because protests are an integral part of the revolutionary repertoire [Lawson 2019]) in many countries around the world, thus forming revolutionary waves of processes (Grinin and Grinin 2022). The above-mentioned subjectivity of the English-language media may hinder an adequate perception of the globality of the waves of destabilization and the World-System triggers. In addition, the inclusion of Arabic, which is widely spoken in the Middle East, North Africa and partly in Macrosahel, allows us to record in more detail the processes taking place in the Afrasian macrozone of instability (Korotayev et al. 2016).

In recent decades, globalization has significantly exacerbated the problem of illumination. Despite the fact that, in the context of globalization, more and more English-language news sources and newspapers are actively reporting news around the world (Herkenrath and Knoll 2011), the narrative and evaluations used in the article are very important in the computer analysis of the text. For this, there is a separate method within Natural Language Processing – sentiment analysis. For a more comprehensive coverage of events, it is therefore crucial to include sources in different languages – because they use completely different narratives. For example, comparative studies have shown that the narrative of protests in India in English-language newspapers differs significantly from the coverage in Hindi newspapers (O’Brochta 2019). This is especially evident in cases of overlapping narratives within different parts of the World System: for example, coverage of protests in Hong Kong in Mandarin Chinese is usually accompanied by negative comments about the protesters' actions, while in English and Cantonese Chinese the protesters are usually perceived as honest fighters against an authoritarian political regime (Zhang and Pan 2019). However, the problem is not limited to this – the ideology of the media can influence what news is reported about the protests (Oliver and Maney 2000). For example, conservative media had the lowest coverage and support for BLM protests in the United States in 2020–2021 (Brown and Mourão 2022). Therefore, the choice of a small number of languages may lead to a misperception of the intensity of the protests in the computer analysis. To avoid these problems in our study, we used sources in different languages, from different regions and guided by different ideologies.

It also provides a new empirical argument that the Arab Spring and the new waves of protests in recent years are global rather than regional phenomena. By analysing information from the media in nine languages at once – English, Arabic, Chinese (Mandarin), Hindi, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German and Russian – the most complete monthly picture of the protest dynamics in recent years – from 2005 to 2021 – is given. However, it should be noted that this work is the first preliminary analysis of the information we have collected and the first consideration of protest dynamics in a global context, using the example of several macro-regions.

Data and Methods

To search for news reports describing protest events, we used the keywords obtained by Andrew Martin and colleagues, which have shown high accuracy in assessing protest activity (Martin et al. 2017). The resulting English words were translated into other languages with the help of regional studies colleagues to avoid incorrect and direct translations.

As sources, we used a large number of media in the nine languages we selected, which are presented in the Google News aggregator. At first glance, it would be possible to use major news agencies with a presence in the main countries of the world, such as AFP or Reuters. However, other researchers point out that news agencies have selective coverage of their correspondents and focus mainly on news from the central part of the region. Another major problem with this type of research is the heterogeneity of the sources studied. The main problem in the analysis of news articles (even with a fairly large amount of material collected) is that if we use only one set of news sources, they will be biased in one way or another due to editorial policy. To avoid this problem as much as possible, it is necessary to collect data from the largest number of available sources.

We translated the information collected in various languages into English so that the location of the event could be determined automatically, because simply assigning all articles about protests in this language to the language region is an obvious mistake – the Arab Spring took place in the Arab world, but the events were mentioned both in Russian and Hindi. The simplest and at the same time the least obvious approach would be to divide the task of assigning news to a place into two stages: in the first stage, we find all the references to the location that are in the country, and in the second stage, we correlate all these geographical references with the countries themselves. In this ways, we obtain a database in which the text corresponds to the list of countries mentioned in it. In general, there are several ways to solve this problem. In our work, we will use the method proposed by Kai Sun and colleagues (Sun et al. 2019); their method is mainly based on the creation of a large database of unique geographical indications, according to which a correspondence is created between the places mentioned and the country in which they are located.

The result was a list of more than 520,000 articles with 33 words in nine languages from January 2005 to December 2021, an average of about 15,000 entries per word.

However, we cannot use the nominal values of country mentions in different news sources obtained by the keywords we have identified. At the very list, such an approach will produce quite an expected trend of self-accelerating growth of mentions for each country and the world as a whole for each language and each word in it. This is due to the gradual expansion of news coverage in different countries (there is more news each year due to the emergence of new sources of information, the increased availability of the Internet, the gradual transition of traditional news agencies to the digital environment, as well as a huge increase in the number of publications indexed in Google News). To do this, we standardized our data on the number of news sources per month and then used the principal component method to aggregatee information on 33 words in languages into one variable that can be considered as an index of protest activity.

This paper will present mainly descriptive statistics on the database we have obtained; however, for the analysis we will use the decomposition method necessary for the analysis of time series, that is, the monthly index of protest activity obtained. Thus, the observed value of the index for each month and the trend, which is free of seasonality, are presented.

Results

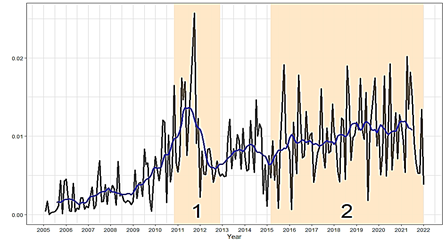

Figure 1 shows monthly protest activity from January 2005 to December 2021 in North Africa and West Asia, which forms the basis of the Afroasian macro-zone of instability. At the same time, the graph shows both observed values, which have a certain seasonality and large peaks, and trend values, which have a smoother and more informative line reflecting the overall dynamics. Immediately noticeable are two waves of protests: from 2011 (and an increase also from 2009) and from 2015. At the same time, if the first wave (number 1 in Figure 1, which can be described as a reflection of the ‘Arab Spring’) generally ended in 2013, the second is in an active ‘creeping’ phase: a continuous increase in protest activity is visible, but a clear ‘ejection’ has not yet occurred, which leads to the assumption that it must happen in the future. At the same time, it is interesting to note that between the first and second waves (numbers 1 and 2 in Figure 1) there was also a small wave with a peak in the first half of 2014. Apparently, this is a kind of echo of the ‘Arab Spring’, which was not as large.

Fig. 1. Index of protest activity from North Africa and West Asia

Data from Global protest database (does not require permission).

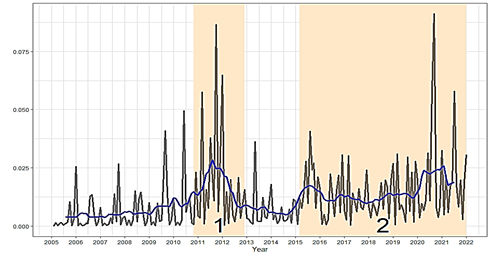

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of protest activity in Europe and North America, reflecting the processes of instability at the core of the World System.

Fig. 2. Index of protest activity from Europe and North America

Data from Global protest database (does not require permission).

A somewhat similar dynamic with North Africa and West Asia is immediately apparent: two waves are also visible, with the first also beginning in 2009 and the second not yet finished. At the same time, there is a clear difference – the echo of the first wave only seems to have started in 2015, whereas in the previous macro-region it already passed in the first half of 2014. It is also noteworthy that the second wave began to clearly accelerate in 2020 (despite, and sometimes thanks to, the restrictive measures taken by most of the countries in this macro-region in connection with the pandemic). This can largely be explained by the activation of the BLM movement, ‘anti-Covid’ and socio-economic protests (largely ‘anti-inflationary’ after the end of the active phase of the pandemic) in most countries of this macro-region – the USA, France, the UK and others.

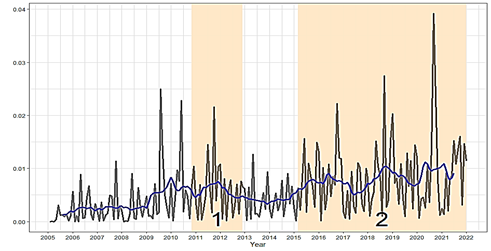

Figure 3 shows the dynamics of protest activity in Latin America. Interestingly, the Arab Spring of 2011–2013 is also visible here, but on a much smaller scale. In addition, the second wave of protests is also noticeable, gaining momentum after 2015: a series of microwaves is noticeable – from 2015 to mid-2017, then from 2018 to 2020, and then a new bulge. At the same time, all the bulges become larger over time, which allows us to make rather pessimistic forecasts for a further increase in protest activity in this macro-region. It seems important to note that the first wave of protests in Latin America began already after 2009, so that the first wave actually occurred in 2009–2012/13.

Fig. 3. Index of protest activity in Latin America

Data from Global protest database (does not require permission).

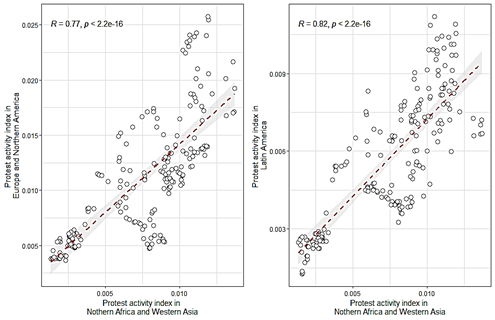

Having described the trends in protest activity in different parts of the world, we can see that they all follow a very similar scenario. In fact, North America, together with Europe, and Latin America, and North Africa, together with West Asia, experienced a strong wave of protest instability after 2009, and its ‘echo’ afterwards. At the same time, a new wave of protests, which has not yet reached its peak, can be observed in all regions. In this respect, we can look at the scatterplots between the trend values of the protest activity index of different macro-regions in Figure 4. The abscissas in both cases show the values for North Africa and West Asia, and the ordinates on the left and right sides of the figure show the values for North America and Europe and Latin America respectively. It is noticeable that there is a connection between the trends in protest activity in these seemingly very different macro-regions. The correlation is highly significant and positive in both cases, indicating a single direction of the protest dynamics in these regions and, apparently, in the world as a whole.

Fig. 4. Scatterplot of the trend of the protest activity index between different regions

Data from Global protest database (does not require permission).

Also, to confirm the similarity of protest trends in the regions under consideration, Figure 5 shows the trend values of the Protest Activity Index in Latin America, North America and Europe, and North Africa and West Asia. Again, two waves are clearly visible – 2011–2013 (number 1) and 2015– present (number 2). At the same time, it is extremely interesting to note that the first wave started in 2009, two years before the Arab Spring, which is considered a trigger for instability around the world. It is also worth noting that North America and Europe are leaders in terms of protest activity, bypassing all other regions. In general, this is not surprising: we are considering only protest, unarmed activity, whereas in developing countries and in Latin America, North Africa and West Asia, riots and armed demonstrations play an important role. In addition, we cannot exclude the English bias described above, which we have tried to eliminate, but it is still extremely difficult to do completely in automated news gathering.

Fig. 5. Trend values of the protest activity index in some macro-regions

Data from Global protest database (does not require permission).

Conclusion

Based on the assumption that revolutions never occur in isolation (Grinin and Grinin 2022: 178–197), together with the results of the empirical research, presented above, we conclude that the protest activities observed in different parts of the world since the first decade of the twenty-first century are synchronised into a new global trend. The modern World-System does not allow instability in one region to be without consequences for another. Thus, the civil war in Syria caused the migrant crisis in Europe, the wave of refugees from the MENA region caused tensions between Belarus and Europe (Grinin and Grinin 2022). Since 2012, the number of refugees in the world has been growing rapidly, with the largest increase in 2022, mainly among Ukrainians, Venezuelans and Afghans (52 per cent of all refugees) (UNHCR 2023). Our results show that the echoes of the ‘Arab Spring’ have been felt in all regions, if not in serious socio-political revolutions, then at least in massive protest and revolutionary episodes.

The analysis in this article shows that since 2009 all the macro-regions considered (Latin America, North America and Europe, and North Africa and West Asia) have followed a common scenario. There is a single direction of the protest dynamics in these regions and, apparently, in the world as a whole. Meanwhile, a new global wave of protests, which has not yet turned into a significant ‘protest boom’, can be observed in the near future, as was the case with the previous waves of protests. Taking into account that we are in the period of drastic, deep and interrelated transformations, such as the change of the world order, the slowdown of the world economy, the transition to a new technological cycle, growing tensions between countries, we can assume that the rise of protests is a reflection of these transformations and can be considered as one of the main driving forces of historical progress, leading to new types of regimes and reshaping the World-System itself (Grinin 2012, 2018, 2019; Grinin and Korotayev 2016). Moreover, the new wave of revolutionary events brings less developed countries out of isolation (Grinin and Grinin 2022). Thus, the echo of the Arab spring reached Tropical Arica, which is now undergoing a process similar to the Reformation in Europe in the sixteenth century (Grinin 2019; Grinin, Korotayev, and Tausch 2019), or the Islamic revival in the mid-twentieth century (Huntington 1996). This process, along with the numerous problems caused by destabilization, creates the ground for new solutions and opportunities that could lead too positive changes in the long run (Grinin and Grinin 2022).

NOTE

* Here and further, following the work of Kadivar and Ketchley (2018), non-violence is understood not as the actual absence of cruelty, but as the non-use of factory weapons by the protesters.

REFERENCES

Blair, R. A., and Sambanis, N. 2020. Forecasting Civil Wars: Theory and Structure in an Age of ‘Big Data’ and Machine Learning. Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (10): 1885–1915.

Bowlsby, D., Chenoweth, E., Hendrix, C., and Moyer, J. D. 2020. The Future is a Moving Target: Predicting Political Instability. British Journal of Political Science 50 (4): 1405–1417.

Brown, D. K., Mourão, R. R. 2022. No Reckoning for the Right: How Political Ideology, Protest Tolerance and News Consumption Affect Support Black Lives Matter Protests. Political Communication 39 (6): 737–754.

Day, J., Pinckney, J., and Chenoweth, E. 2015. Collecting Data on Nonviolent Action: Lessons Learned and Ways Forward. Journal of Peace Research 52 (1): 129–133.

Fearon, J. D., and Laitin, D. D. 2003. Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War. American Political Science Review 97 (01): 75–90. URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055403000534.

Goldsmith, B. E., Butcher, C. R., Semenovich, D., and Sowmya, A. 2013. Forecasting the Onset of Genocide and Politicide: Annual Out-of-sample Forecasts on a Global Dataset, 1988–2003. Journal of Peace Research 50 (4): 437–452.

Goldstone, J. A., Bates, R. H., Epstein, D. L., Gurr, T. R., Lustik, M. B., Marshall, M. G., Ulfelder, J., and Woodward, M. 2010. A Global Model for Forecasting Political Instability. American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 190–208. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00426.x.

Grinin, L. E. 2012. Arab Spring and Reconfiguration of the World-System. In Korotayev, A. V., Zinkina, Yu. V., and Khodunova, A. S. (eds.), Systemic Monitoring of Global and Regional Risks (pp. 188–223). Moscow: LIBROKOM/URSS. Original in Russian (Гри-нин, Л. Е. Арабская весна и реконфигурация Мир-Системы. В: Коротаев, А. В., Зинькина, Ю. В., Ходунов, А. С. (ред.), Системный мониторинг глобальных и региональных рисков: Арабская весна 2011 года, c. 188–223. М.: ЛКИ).

Grinin, L. E. 2018. Revolutions and Historical Process. Journal of Globalization Studies 9 (2): 126–141.

Grinin, L. 2019. Revolutions and Historical Process. Social Evolution & History 18 (2): 260–285.

Grinin, L. E., and Korotayev, A. V. 2016. MENA Region and the Possible Beginning of World System Reconfiguration. In Erdoğdu, M. M., and Christiansen, B. (eds.), Comparative Political and Economic Perspectives on the MENA Region (pp. 28– 58). Hershey PA: Information Science Reference, An Imprint of IGI Global.

Grinin, L., and Grinin, A. 2022. The Current Wave of Revolutions in the World-System and Its Zones. Journal of Globalization Studies 13 (2): 178–197.

Grinin, L., Korotayev, A., Tausch, A. 2019. Islamism, Arab Spring and Democracy: World System and World Values Perspectives. Cham: Springer.

Hegre, H., Karlsen, J., Nygård, H. M., Strand, H., and Urdal, H. 2013. Predicting armed conflict, 2010–2050. International Studies Quarterly 57 (2): 250–270.

Herkenrath, M., and Knoll, A. 2011. Protest Events in International Press Coverage: An Empirical Critique of Cross-National Conflict Databases. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52 (3): 163–180.

Huntington, S. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Jenkins, J. C., and Maher, T. V. 2016. What should we do about Source Selection in Event Data? Challenges, Progress, and Possible Solutions. International Journal of Sociology 46 (1): 42–57.

Kadivar, M. A., and Ketchley, N. 2018. Sticks, Stones, and Molotov Cocktails: Unarmed Collective Violence and Democratization. Socius 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118773614

Kennedy, R. 2015. Making Useful Conflict Predictions: Methods for Addressing Skewed Classes and Implementing Cost-Sensitive Learning in the Study of State Failure. Journal of Peace Research 52 (5): 649–664.

King, G., and Zeng, L. 2001. Improving Forecasts of State Failure. World Politics 53 (4): 623–658.

Korotayev A., Issaev L., Rudenko M., Shishkina A., and Ivanov E. 2016. Afrasian Instability Zone and its Historical Background. Social Evolution & History 15 (2): 120–140.

Korotayev, A., Meshcherina, K., and Shishkina, A. 2018. A Wave of Global Sociopolitical Destabilization of the 2010s: A Quantitative Analysis. Democracy and Security 14 (4): 331–357.

Lawson, G. 2019. Anatomies of Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, A. W., Rafail, P., and McCarthy, J. D. 2017. What a Story? Social Forces 96 (2): 779–802.

O’Brochta, W. 2019. Pick Your Language: How Riot Reporting Differs between English and Hindi Newspapers in India. Asian Journal of Communication 29 (5): 405–423.

Oliver, P. E., Maney, G. M. 2000. Political Processes and Local Newspaper Coverage of Protest Events: From Selection Bias to Triadic Interactions. American Journal of Sociology 106 (2): 463–505.

Rafail, P., McCarthy, J. D., and Sullivan, S. 2019. Local Receptivity Climates and the Dynamics of Media Attention to Protest. Mobilization: An International Quarterly 24 (1): 1–18.

UNHCR. 2023. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2022. Data and Statistics. https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends.

Sun K., Zhu Y., Song J. 2019. Progress and Challenges on Entity Alignment of Geographic Knowledge Bases. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 8 (2): 77–102.

Zhang, H., Pan, J. 2019. Casm: A Deep-Learning Approach for Identifying Collective Action Events with Text and Image Data from Social Media. Sociological Methodology 49 (1): 1–57.